This week, as the east coast of the United States was deluged with rain, I basked in beautiful San Diego sun while attending the Logimed USA event. This was WBR’s first event in the United States targeted for the Medical Device Supply Chain Leader. I had not been to a medical device event and I wanted to listen.

When I finished my presentation on “past practices,” that I cannot call “best practices,” and outlined the methodology for the upcoming Supply Chain Index, a woman who had listened intently in the audience told me that I had thrown “cold water” on the audience.

I said, “I am sorry, but I think that the industry needs to face some cold hard facts.” The discussions at the event reminded me of dialogue that I heard in other industries a decade ago. So, the title of this post is Throwback Thursday.

Current State

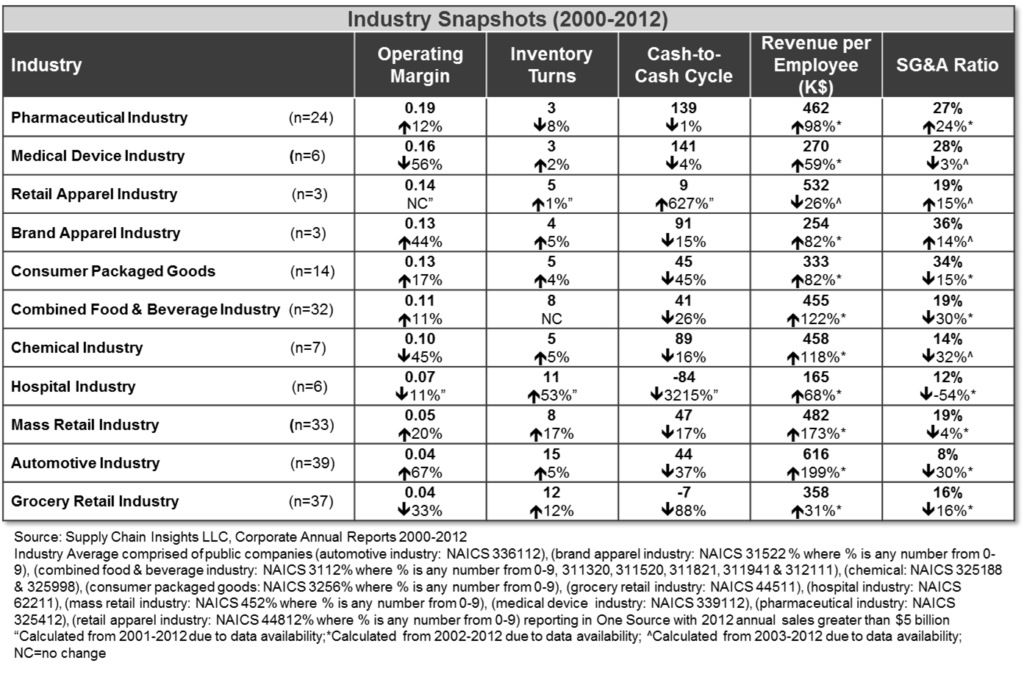

Today, managing a medical device supply chain is tougher. It is much more complex than it was a decade ago. Many are enamored with the “good old days.” As shown in Table 1, operating margin has declined 16% over the course of the decade. This precipitous drop in margin hurts. As hospitals adopted consignment planning programs, inventory progress slowed. The turns are the lowest of any industry, and despite investments in technologies and processes, inventory turns have only improved 3%, and Cash-T0-Cash (C2C) cycles have declined 4%. Companies are feeling pain.

Table 1.

This is why I think that the industry needs to get serious about supply chain management. And, I believe that it needs to happen FAST! There is no time for whining. The operating margin for the medical device industry is 4X that of the automotive manufacturer and 2x the margin of the hospital. The business operating environment has changed. The pressures of affordable care and global regulation are transforming the market, but are they redefining the supply chain fast enough? I don’t think so.

My message in the presentation was simple. There is an inverse relationship between margin and supply chain excellence. Companies with lower margins tend to get better at supply chain faster. It matters more. In these industries, the adoption of technologies and processes becomes essential to doing business. In industries with high margin, change happens slowly and the leaders tend to be insular.

In doing studies of different industry subgroups, we find that the medical device industry is resilient. The patterns at the intersection of inventory turns and operating margin are tighter than other industries, but we do not find “strength” or year-over-year performance improvements in the numbers. Note that in this comparison of the top three medical device companies in Figure 1, that Zimmer is substantially underperforming against the other two, and that all three companies are going backwards in operating margin. However, all three of these industry leaders have margin averages that are SIGNIFICANTLY better than the industry average for the period of 16%, but are underperforming on inventory turns.

Change is under foot. Zimmer Holdings is growing larger. Last week Zimmer announced the acquisition of Biomet for a cash and stock transaction valued at approximately $13.35 billion.

Figure 1.

This transaction, which is subject to customary closing conditions and regulatory approvals, is expected to close in the first quarter of 2015. The merger of Zimmer and Biomet will position the combined company as a leader in the $45 billion musculoskeletal industry. Zimmer’s strategic framework focuses on growth, operational excellence and prudent capital allocation. Let’s hope that this will drive channel leadership that is sorely needed.

My Challenge.

So, my challenge for these three companies is: leaders need to lead. We don’t have time for Throwback Thursday. This value chain needs a supply chain leader. Hospitals are too fragmented to lead, and the GPOs are dysfunctional. We need for supply chain leadership to step up to the plate.

Why do I call this Throwback Thursday? It is because the conversations at the conference were yesterday’s discussions. The leaders from the medical device industry need to learn from both the success and failures in other industries. Here are five areas where I would start:

–Scorecards. In healthcare, there are no customer scorecards. While companies talk about being customer-centric, there is little recognition that the customer has changed from a focus on the physician to the care center and in some cases to wellness in the patient’s home. My take: The industry is 10-15 years behind in measuring itself in the “eyes of the customer.” To build more effective outside-in processes, the focus needs to be less on a sales-driven organization and more on effective channel usage. Leaders need to start a system to improve measurement and tie performance to buying incentives.

–Embrace Standards. GS1 standards adoption is sooooooooooooo slow. I heard Stryker share the story of adoption over a period of five years at the GHX conference last year. At the Logimed conference, no one in the audience was aggressively adopting the standards. My take: When the adoption of standards happened in CPG/retail, Danny Wegman of Wegmans, Sandy Douglas of Coca-Cola, and Tim Smucker of Smucker’s led the charge. This industry has no leader(s) driving the initiative. Instead, companies are letting the federal government stuff a standards mandate with UDI. The leaders in CPG drove the change while medical device leaders are fighting it. The discussion that I heard at this conference was reminiscent of the laggards in CPG discussing GS1 standards in 1999.

-Get the Labels Right. With changing legislation and country-specific regulations, having the right label on the product is a big deal. My Take: I was at a hospital last month watching the receiving of agents and pharmaceutical products. 30% of the items did not scan. Hospitals have aggressively adopted B2B automation. This has happened faster in hospitals than in retail. As a result, scanning has grown in importance. Late-stage postponement and effective in-country labeling and tracking is essential. I dusted off a 2002 presentation from P&G to share with the audience. Yet, the attendees wanted to discuss Lean warehousing.

-Aggressively Get and Use Channel Data. With the shift of inventory back in the supply chain, there is a lot of discussion on Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI). In the discussions, there was not one mention of usage data. My take: VMI should be used to sense and respond to channel demand. The shift of inventory without the sharing of data is a mistake. Let’s learn from the lessons of the last decade. For more on the state of VMI, please reference last week’s blog Stasis.

–Share Data. The clock speed, and the need for supply chain decisions, is accelerating. There is no Walmart or channel power broker in this value network. As a result, the large medical device companies need to decide on a value network and endorse it to get channel data. The goal needs to be the use of daily data daily. Right now there are many contenders. My POV. The leaders in the medical device industry need to pick—GHX, Owens and Minor, Cardinal Health, or Integrichain—and support an industry standard. The supply chain will not improve unless the processes move from Inside-out to Outside-in.

Next week I will be speaking on Retail Scorecard adoption as part of the rVCF conference, and then I fly to Turkey to speak on the Race for Supply Chain 2020. I hope to see you in my travels.

At Supply Chain Insights, we are busy preparing the Supply Chain Index methodology for a May 13th launch. Don’t miss it. To be sure that you get our research through the summer, please sign up for our newsletter.

And finally, our survey on supply chain planning is closing. In this survey we find out some benchmark metrics on the number of demand planners per item, and the rate of adoption of demand and supply chain planning systems. If you are questioning where you are on your journey and how you compare to others, this survey is one that you do not want to miss. And, like all surveys, we share the final results and keep the individual responses confidential.

Beyond Rabbit Ears on a Black & White TV

When I was a young girl, we received one television channel. Rabbit ears on top of the TV helped us get more channels. We loved