Tonight, as I flew back from SAP Insider, three blog posts danced around in my head. I thought about the looming deadline on my book and two presentations to finish for next week. I find myself with lots of ideas fighting in my mind to get to paper.

As I start this blog post, I face a conundrum. Which blog post to write? I am excited about all three. So, which shall it be? Rock, scissors, paper…. Ah, yes, there it is. Tonight, I will write on the Pitfalls and Potholes of Integrated Business Planning (IBP). This weekend, I will post my thoughts on the other two blog posts (Seven Trends that Excite Me and Big Data Supply Chains).

Some History

I have been an analyst for ten years. In 2002, I worked at Gartner Group as a supply chain analyst for two years. This was followed by six years at AMR Research, two years at Altimeter and now I continue my work as the founder of Supply Chain Insights. I have probably spoken to over 300 companies on Sales and Operations Planning.

In the 1990s, I worked for a supply chain planning company and worked closely with a team to write requirements for demand planning software. I had ridden the wave of demand planning. I was a demand planner in three manufacturing companies. As I entered the analyst world, I thought that I knew a lot about forecasting. I was wrong. I knew only my experience.

In 2002, as an analyst at Gartner Group, I partnered with two analysts that I respected to write a note on Integrated Business Planning. In the note, we recommended that companies tightly integrate their sales, financial and manufacturing forecasting plans. I waxed eloquently (at least I thought so then) on why this made sense. Based on experience with clients, and the many years of research, I realize that we got it wrong and gave teams bad advice. So, as I hear people talk about Integrated Business Planning, I get uncomfortable, because I also hear people getting it wrong.

When I first started as an analyst at AMR Research, my first two reports were How do I know I have a Good Forecast, and the Evolution of Sales and Operations Processes. I was asked by clients to research these topics to understand the “change management” issues and to share insights on how to avoid these potholes. My experience deepened through this research.

Common Mistakes

So, I go way back…. In this period of time, I saw the writing on the term Integrated Business Planning blossom. But, as the term gains more usage and the citations skyrocket, I have seen the concepts become more confused. I feel that more people say it than know what it means. Next week, I am speaking on the topic at the S&OP IE event in Miami. Here I share my perspective in advance. There are five common mistakes I see people make:

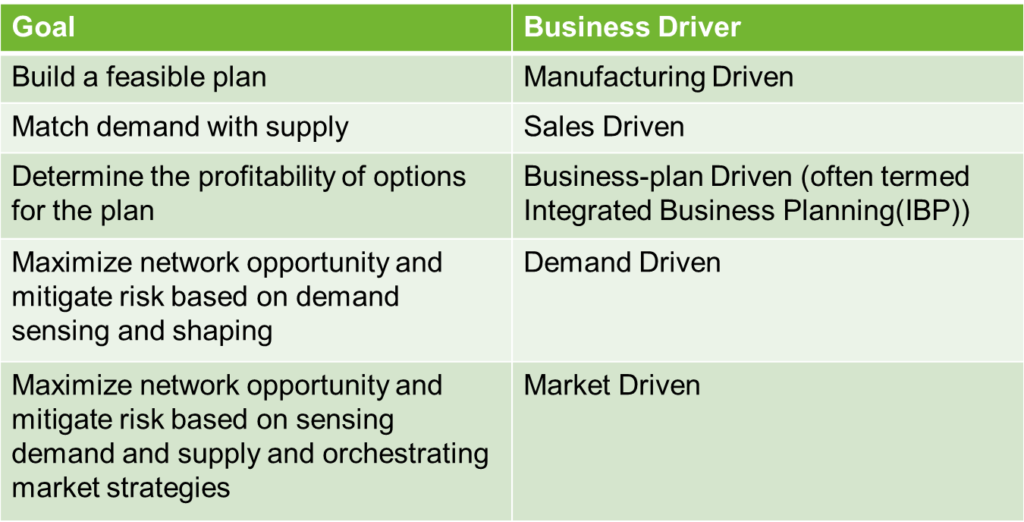

Mistake #1: Jumping into the Deep End without a Paddle. Integrated Business Planning is the third step of maturity in S&OP process implementation. Each stage has a different goal and requires a different information technology (IT) architecture. I find that company maturity can easily be determined by answering three questions:

- What is the goal of your S&OP Process?

- How do you make decisions?

- What do you measure?

Over 95% of companies that I talk to jump into planning their S&OP processes without answering these three questions. The goals are progressive within the S&OP process with each step building on the capabilities of the prior. I find that many companies will throw around the terms “IBP,” “SIOP,” and “S&OP” without ever being clear on the goal, or understanding what each individual on the team means when they say the term.

Sometimes, I am called in to be a referee in an almost religious argument about the “best term” to use for the process. I am fascinated about the love affair with terms. I struggle to understand why companies want to talk about the name without ever getting grounded on the process or clear on the goal.

Sometimes, I am called in to be a referee in an almost religious argument about the “best term” to use for the process. I am fascinated about the love affair with terms. I struggle to understand why companies want to talk about the name without ever getting grounded on the process or clear on the goal.

When I ask companies to define their goal, I usually get a pregnant silence. The reason is that most companies start the discussion on Integrated Planning without first asking, “What is the goal?” And, without realizing that the progression is a set of steps.

Usually, through many failed attempts, they find that they must first be able to build a process to do “what if “analysis to determine a feasible plan before attempting to match demand with supply. And that mastering the process of matching demand with supply is a pre-requisite to successful Integrated Business Planning (IBP).

Another common mistake is a failure to look at the definitions of the data models, forecasts and the business requirements. This usually happens because the individuals on a team are very steeped in the definitions of the term “forecast” within their own functions. Let me explain. In the first two levels of the S&OP process, companies are modeling volume. In the third stage, the modeling shifts to trade-off cost and revenue trade-offs for IBP. These are very different architectures, with different processes, and the first two steps need to be mastered before tackling the third. Just think, what good is a spreadsheet modeling financial data if the plan is not feasible?

In this process, teams quickly find that a forecast is not a forecast is not a forecast. As companies attempt to do financial modeling, they quickly find that the data model needs to be able to determine the right trade-offs of mix (changes in products), units (many companies have multiple equivalent units), fixed versus variable cost impacts based on demand and supply variability, and the margin implications of lifecycles in new product launch. It is not as easy as just plugging data into an Excel spreadsheet. They turn to tools like Jonova, Riverlogic and SAS.

While Integrated Business Planning may be a sexy topic, the basics of constraint-based manufacturing, inventory planning and distribution requirements planning must be modeled to ensure there is a feasible plan before calculating cost and profitability trade-offs. This requires the use of very industry-specific technologies from companies like Aspentech, JDA, Infor, Kinaxis, Logility, SAP APO, Oracle APS, Wam Systems and Zemeter.

Mistake #2. Clarify the Role of the Budget. The number one change management issue for IBP is determing the role of the budget. A company immature in the process will attempt to use the S&OP process as a tool to make the budget. They will often constrain the outcome of the process in an attempt to ensure that the budget goals are met.

A more mature company realizes that the budget is out of date the minute that it is developed. They also realize that to maximize corporate opportunity and mitigate risks, the company will use the S&OP process to drive budget updates, but will never constrain the S&OP process with the original budget.

The role of the budget, and the governance model around making decisions, is a major hurdle to overcome early.

Mistake #3. Tight Integration of the Forecasts. In short, a forecast is not a forecast is not a forecast. What do I mean? A sales forecast is usually a pipeline view of expected sales. It usually has a 3-4 month duration. The forecast is usually at the product or family level of expected sales and is often forecasted in currency (dollars, euros, pounds). It is not without problems. It carries a strong bias and error.

Many companies, early into the process, make the mistake of saying “If I want to know what I am really going to sell, I will ask sales.” Unfortunately, it is not that simple. A sales forecast has a high bias and error due to internal reward systems. Sales people by definition are “coin operated.” They are usually paid by commissions. As a result, sales input into consensus forecasting usually carries the highest bias and error of any group in the organization. Companies need to overcome this challenge by weighting the input based on historic bias and error.

In contrast a supply chain forecast is usually a constrained forecast that reflects seasonal builds, event plans, new-product launch activities, and price changes. It is built from the bottom-up using statistical models based on historical shipment and order data. It is a very granular volume forecast. It has a long duration because its primary goal is to plan assets and manage inbound materials. It also has its own set of problems. It is often a rearview mirror look. Since it is based on history, it can quickly get out of date with the market unless it is corrected with channel, often referred to as downstream, data.

A budget forecast is also usually based on history. It is at a high level of granularity and is usually based on the corporate fiscal year. It is also not without its problems. It is hedged to ensure that the organization can make targets.

In short, each forecast has a different unit of measure, time duration, granularity and bias. None of the three have a common data model. And none of the three come close to reflecting what is going to be sold in the actual market. As a result, tight integration of these three forecasts is usually an exercise in futility.

Instead, companies need to invest in a platform to enable synchronization of the three forecasting types while rectifying the differences in data models. This capability is termed demand translation. It allows the translation of data across the three forecasting models. It helps to translate the “ship to” views to the “ship from” forecasting views and allows for the modeling of bias and error of the three organizational forecasting plans. Many companies handle this the old-fashioned way through the sharing of spreadsheets. More sophisticated companies are automating it through technologies. “What if” capabilities are essential. There are three demand translation tools on the market today: Kinaxis Rapid Response, Steelwedge S&OP and SAP HANA.

For this reason, one number forecasting should not be the goal. Instead, the goal should be a common plan based on shared assumptions and consensus of market drivers. The focus needs to be outside-in. This is MUCH more important than one number. I feel that we have spent too many wasted hours trying to get perfect on imperfect numbers.

Mistake #4. The Efficient Supply Chain is Usually not the most Effective Supply Chain. There is the need for Supply Chain Strategy. Before companies begin the discussion on the integration of business plans, there needs to be agreement on “what good looks like.” For 94% of companies, this is not clear.

When companies begin to do “what if modeling” on financial options, a hurdle is how to make the right cross-functional trade-offs between make, source and deliver. This can only be solved by working on a supply chain strategy. Key questions to answer are:

- How many supply chains do I have?

- What is the goal of each supply chain?

- What drives value in the value network? How do I align to maximize value?

- What are the right measurements for alignment between source, make and deliver? And how does this align with the channel strategy?

- What is the impact of product and customer complexity? How do I best design to mitigate the rise in complexity?

At the end of this activity, companies learn that the most effective supply chain is often not the most efficient supply chain. (An efficient supply chain is defined as the lowest cost per case.) As a result, the journey for integrated business planning is rife with issues on how to design the supply chain to drive alignment. I find through research that only 6% of companies have a clear supply chain strategy. As companies drive discussions on how to best make the organizational trade-offs in IBP, they find that these decisions need to be grounded in supply chain strategy. This is hard, but necessary work. A supply chain strategy is needed to translate the business strategy into action.

Mistake #5. IBP is not the Holy Grail. While each step of the S&OP maturity model gives progressive and increasing returns, IBP is in the middle, not the end, of the S&OP maturity model. It is not nirvana.

The issue is that, after all this work, it is still an inside-out not outside-in view. Let me explain. It is an internal view. It is the use of history (orders and shipments) to make decisions. As a result, while companies can achieve excellence at IBP, they are still insulated from sensing and shaping demand or supply based on market shifts. To become demand or market driven, the company needs to build the architecture from the outside in which often requires the redeployment of conventional Advanced Planning (APS) models for demand and supply modeling. As a result, I often see the most advanced companies skip this step. They first built demand-driven or market-driven capabilities and then come back and align business plans.

Wrap-up

In short, sales driven is not demand driven. Demand driven is not market driven. A forecast is not a forecast is not a forecast. The best success with S&OP happens when it is designed from the outside-in. But, to get to this goal, companies need to build the competency, ask the right questions and ensure that they have purchased the right architectures. Goal alignment with IT architectures is essential. Clarity on supply chain strategy is paramount.

It all starts with the answers to three common questions, but often gets tangled by discussions full of acronyms, well-meaning consultants, and internal teams engaging in religious arguments. Break this pattern by getting real clear on the answers to some very basic questions. It is my hope that through this blog I have sensitized you to the issues. I am now on to write and finish the other blog posts. You will find me on a plane, on my way to Miami on Sunday, busy at my keyboard in seat 2B.

As I pack my bag, I fear that next week I will have to sit through two days of presentations that will unknowingly give bad advice because they have not experienced the complexities. I will probably feel the need to twitch through these sessions. I expect to have an allergic reaction to many of the presentations. I may need a seatbelt to stay in my seat. You will find me tweeting about them at @lcecere.

I would love to hear your thoughts. What do you think? Please share your experiences with building Integrated Business Planning processes.

If you are interested in more discussion on S&OP, attached are some articles that I have written on the topic:

SAP S&OP Hana: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/sales-and-operations-planning-2/is-the-third-time-the-charm/

IBF Roundtable Summary on a Reliable and Resilient S&OP Process http://www.supplychainshaman.com/sales-and-operations-planning-2/how-do-i-have-a-reliable-and-resilient-sop-process/

Work by SAP on S&OP http://www.supplychainshaman.com/page/2/?s=sales+and+operations+planning

Change Management in S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-excellence/and-the-question-is/

On Horizontal Process Development: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-excellence/we-stumble-forward/

Putting the Pieces Together: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-excellence/sales-and-operations-planning-putting-the-pieces-together/

On Kinaxis for S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/new-technologies/step-up-scm-is-not-a-game-of-horseshoes/

On Flexibility in S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/new-technologies/my-take-supply-chain-future/

Top Five Issues in S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-economic-recovery/loras-top-five-of-the-top-ten/

Avoid a Cookie Cutter Approach in S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/page/8/?s=sales+and+operations+planning

Pearls of Wisdom on S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/page/10/?s=sales+and+operations+planning

On IBP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-planning/enough/

On Change Management in S&OP: http://www.supplychainshaman.com/supply-chain-2/supply-chain-economic-recovery/are-you-only-giving-it-40/