When reviewing strategy decks for supply chain teams, I often see statements like “move from a functional-silo’d focus to a drive a more holistic response.” Or “push a shift from a focus on cost to drive value?” Sound familiar? As an analyst, I am always searching for answers and clear definitions. To help, I will ask, “How do you define value?” Followed by “How are you organized, and what defines functional excellence? And, how do you tie functional excellence to corporate value?”

In this work, my observation is that large companies have a more difficult journey to drive organizational alignment, than smaller companies. This gap grew over the last decade. Companies became less clear on the definition of supply chain excellence and how to implement decision support technologies. As a result, planning teams and functional organizations became more insular and self-serving.

In my research, I find that the lack of alignment has a direct impact to value (operating margin and market price to book value). But, I want to understand this more, and as a result, I have a new study in the field to gain additional insights, and I would love your input. If you answer the survey, I will gladly give you a custom analysis of your organization against the peer group. To respond, follow this link.

To entice you to participate let’s look at the data more closely.

Organizational Alignment

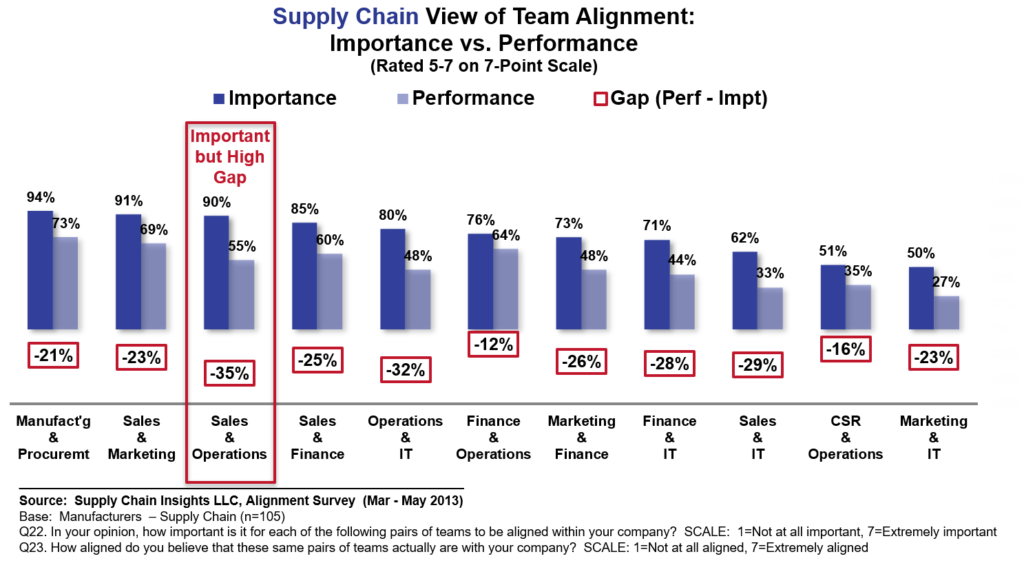

In 2012, I placed the first alignment study in the field. The results were striking. The financial teams, and the Information Technology (IT) groups, did not see alignment gaps, but the supply chain teams felt them and viewed them as a critical performance issue. In each case, teams were asked to rate the importance of being aligned and then judge their internal alignment. In the supply chain team analysis, note the 21% gap between procurement and manufacturing teams, the 35% gap between sales and operations and the 21% gap between finance and operations.

Figure 1. Organizational Alignment 2012

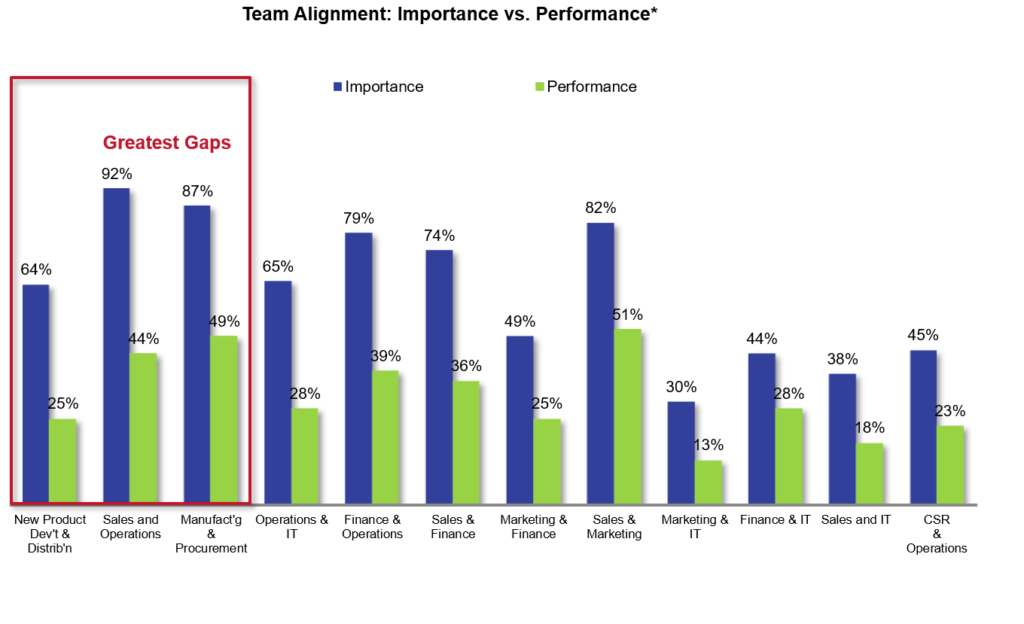

This seemed bad at the time, but little did I know that it would get worse. Note that in 2019, the gaps changed. The gaps doubled between manufacturing and procurement teams (increasing to 39%) and operations and finance teams (increasing to 40%) and grew slightly between sales and operations teams (increasing to 48%). These increasing gaps in alignment and clarity of the definition of supply chain excellence were an unspoken risk entering the pandemic. These gaps are statistically significant at an 80% confidence level, even accounting for the disparities in the sample. The issues are greater for the organization with annual revenues greater than 5B$.

Figure 2. Organizational Alignment in 2019

My Take

In the absence of alignment, organizations face chaos and political gaming.

My first takeaway is the need to do further analysis. I am partnering with a University to analyze the reasons in greater detail, but this work takes many months. But, using myself as an instrument and sharing my observations from working with companies over the past decade, I believe that five factors drove the gaps in alignment:

- Investment in Technologies to Improve Functional Efficiency. Focusing on order-to-cash and procure-to-pay by financial teams and the false belief that tight integration of ERP to decision support would improve results strangled organizations. The massive investments in ERP only made technology providers and consultants rich. But did it add value? The answer is unknown because there are never any after-action reviews. Focusing on transactions at the expense of understanding and harvesting insights from market data resulted in implementing the wrong set of controls. Layering CRM and SRM on top of ERP made sales and procurement more efficient but less effective in working with trading partners and serving the organization.

- Functional Metrics. With the implementation of transactional systems, the focus was on measuring and controlling functional metrics like the lowest manufacturing cost or purchase price variance in procurement. This maniacal focus on improving functional metrics threw the supply chain out of balance and made the organization less able to work together to solve issues.

- Lack of Visibility of Supply Chain Trade-offs to Manage Balance Sheet Impacts. Advanced planning solutions (APS) do not cross over make, source, and deliver with a common data model in the planning horizons. Only 9% of companies designed their supply chains, and 1/3 can analyze what-if analysis. Over 90% of decisions were made on spreadsheets without a focus on buffers and flows. (Demand and supply variability and supply chain complexity is beyond the capability of even the best spreadsheet jockey.) Correction of alignment only happens when business leaders can see and take action to supply chain alignment issues. Standard technology alignment did not enable this analysis.

- Understanding of Supply Chain Excellence by the Executive Teams. As organizations became more global, the need for clear governance and supply chain excellence definitions grew, and few companies filled this gap. As a result, organizations became more political and self-serving.

- False Beliefs. Few consultants understand the supply chain as a complex non-linear system. As result, many perpetuated false beliefs including:

- Save money in the back office and grow the business through these savings. The impact was to shift demand from period to period versus demand shaping, which increased total cost without a positive impact on growth.

- Unabated supply complexity can be managed. Few companies managed the long tail of the supply chain successfully. A SKU is not a SKU. As a result, the longer tail whipped the organization increasing the alignment gaps.

- Long supply chains can be managed effectively with increased demand and supply variability. The focus on lower costs shifted supply into global trade lanes as demand and supply variability increased. No company I know of measured variability regularly and tested the feasibility of the supply chain design. Long supply chain trade lanes are only a good fit when demand and supply variability is low.

- Outsourcing is a viable answer. Outsourcing only makes sense when demand and supply variability is low, and data latency and systems are equal to the rhythms of needing and using data. Most companies outsourced without building capabilities or testing the design. Outsourcing makes sense only when it improves capabilities.

What do you think? I would love your opinion.

Next Steps

So, what you might say? Now is a great time to question the shifts made in the last decade and the balance sheet potential to improve organizational alignment and the organization’s capability to make decisions effectively in times of demand and supply variability. In the process, challenge the basics. We must unlearn to rethink supply chains to unleash value. The start might be participating in our survey to see where you are against your peer group.