As a child, I never painted within the lines. Always as a non-conformist, I pushed the edges and challenged boundaries.

I discovered, as an adult, that I was a Myers-Briggs INFP personality type: I love to create. My imagination goes wild when I see new forms of analytics. I am always thinking about how supply chain planning architectures can change. In contrast, my clients, not so much. I find most accept planning as a technology–and delve in with an implementation focus–few question if they are making better decisions.

In contrast, I am constantly questioning what makes a good decision, how to make better decisions faster, and how new technologies can transform work. Understanding these trends and helping business leaders is my life’s work.

Recently, I presented at the Informs Analytics Conference in Houston and challenged companies to “think out of the box” and define outside-in processes in Supply Chain Planning. Before the session, I sat by a young data scientist. As a recent college graduate, he manages innovation in discrete event simulation for an automotive company. He currently supports the North American manufacturing team and struggles with the imposed standards by the centralized center of excellence. He was frustrated. The reason? The rate and yield goals dictated by the global center of excellence team are not aligned with reality. When I asked about the role of manufacturing in driving supply chain excellence, he did not know. So, I backpedaled and asked about the goal of the simulation in manufacturing. His answer was Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE). When I asked about his perception of the role of OEE to supply chain excellence, he was unsure. This discussion typifies what I see. Young bright graduates are placed within an organization to paint within the lines with no one asking how new technologies can improve work.

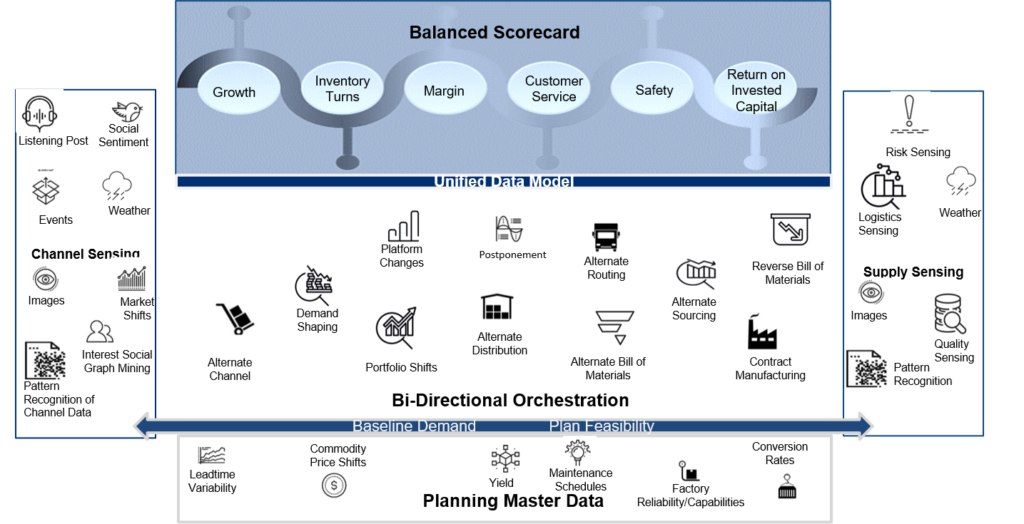

In this blog, I start with a background on the definition of supply chain taxonomies–those that are the basis of reporting in something like the Gartner Magic Quandrant. Since I have covered bi-directional orchestration in previous blogs, here I am going to detail how taxonomies in the area of digital twin and direct procurement need to morph to drive value, but for reference, in Figure 1, I share the previously shared model for bi-directional orchestration.

Figure 1. Bi-directional Orchestration

You might ask, “Lora why do I care about taxonomies?” “Good question,” I would comment. A taxonomy is an unspoken language in software selection and procurement. For example, if a company wants to improve inventory outcomes, teams could purchase DRP, MEIO, or network design. Each is defined by taxonomy. A taxonomy includes a data model definition, outcomes, inputs, and process flows. Alignment on a taxonomy streamlines decisions, implementations, and process integration.

Historical Perspective

I question why companies accept existing taxonomies as a given and challenge bright data scientists to only improve engine outputs within the current definitions.

I often laugh that we paint lipstick on this pig using names like end-to-end planning. (Don’t you think that pink lipstick is beautiful on a pig?) Here I make the argument that our current definition of supply chain planning is out of step to drive agility and resilience, and the lack of understanding by leaders shuts down the opportunity for young and bright data scientists to drive change.

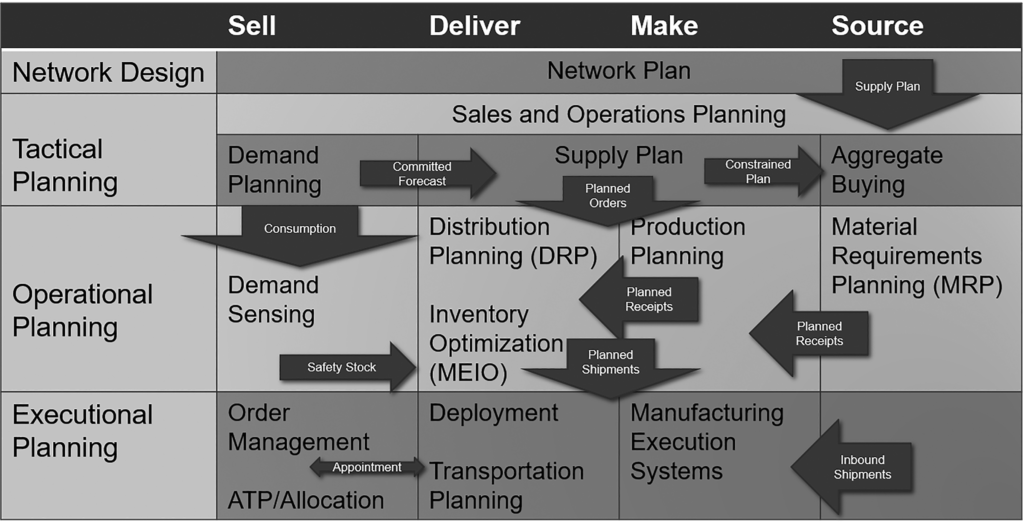

In my world view, there is no technology or system today that helps companies successfully plan end-to-end from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier. The traditional taxonomy definition for supply chain planning that evolved in the 1980s–has not changed much. Supply chains became more global, and variability increased. Yet, the taxonomies remained constant. Sad. The logic shown in Figure 2 is sequential and functional.

Figure 2. Existing Supply Chain Planning Taxonomy

The traditional taxonomy assumes that the order is a good proxy for demand. It also thinks that order consumption logic can improve inventory positions by defining a good safety stock position. The translation of the order signal into a planned order for manufacturing capacity can help minimize constraints. But, the logic falls apart in a world of high variability (like now) when the order is not a good proxy for demand, safety stock is only one element of an inventory strategy, and manufacturing constraints are not the only constraint.

In Figure 2, each box of the traditional planning solution has an engine. The multiple engines don’t align, and the optimization is functional–better output from numerous systems. In addition, when first deployed, organizations did not fine-tune the engines to test the plan. Over time, the engines also needed fine-tuning, but few companies invested in updating the engines. So, when I work with a client, I find primarily old engines idling without clarity on what makes a good plan. Few know how to test distortion, forecastability, and Forecast Value Added. Last week, I laughed when a client told me that “No one is willing to die on a hill for our current processes.” The question is, how do we make it better? We start with the willingness to paint outside of the lines.

“No one is willing to die on the hill for our current processes and technology.”

Current client on thoughts on existing supply chain planning

The models within each of the boxes are different by definition. They do not align, and there is no unified data model. To be specific, there is no commonality between Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP), Manufacturing Planning Systems (MPS), and Transportation Management Solutions (TMS). They are different models. As a result, it is challenging to connect outputs to rules, policies, and strategies. As a result, organizations talk about end-to-end planning while their planning solutions idle in the background.

Could A Digital Twin Be A Unifying Data Model?

My inbox is full of technology companies trying to impress me with their digital twin technology. My question is, “How does a digital twin improve work?” None can answer my question. My concern is that 2% of the back office personnel touch planning systems, and all are unclear on the definition of supply chain excellence.

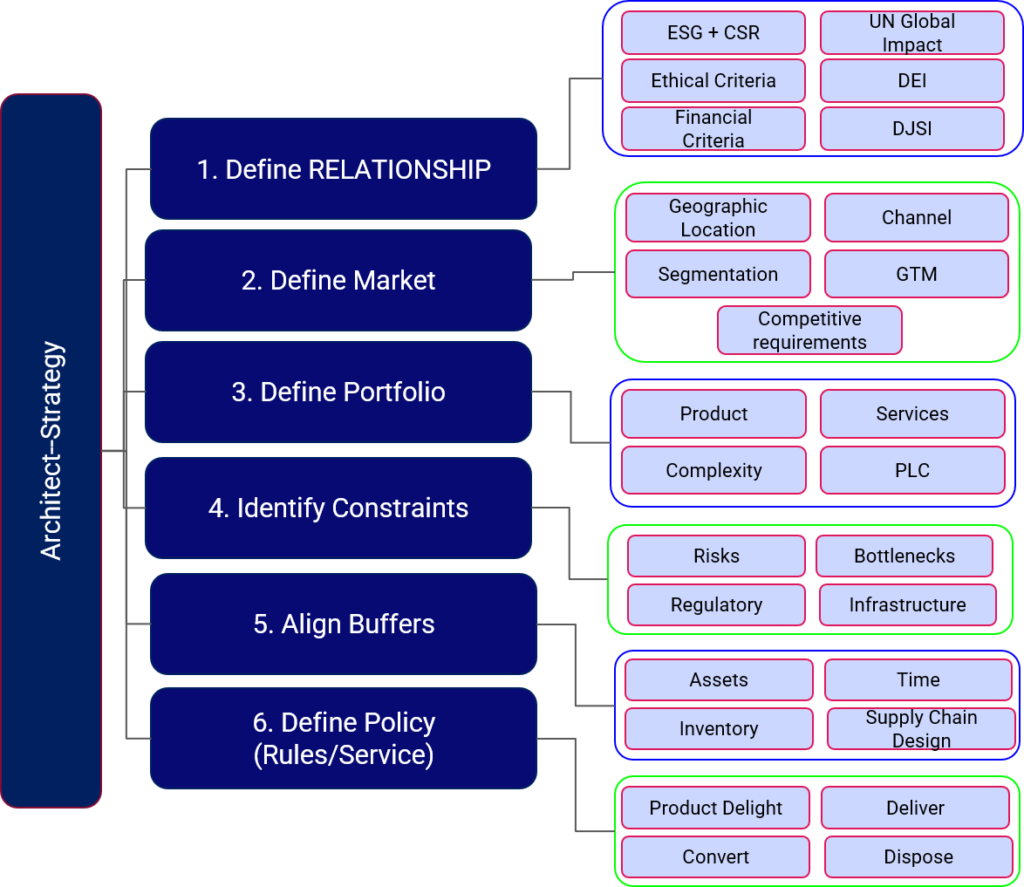

I would like to see the digital twin democratize planning–a collaborative planning technology deployed on every executive’s desk to help them visualize constraints, buffers, volatility, and feasibility. Companies need to design/architect and align on strategy elements to use the digital twin effectively. Building a wireframe using Figure 3 is an excellent place to start.

Figure 3. Required Logical Definition for Digital Twin Implementation

The digital twin is a way for organizations to align. The digital twin will only be a point solution with limited value unless we do this work.

Tackling Procurement

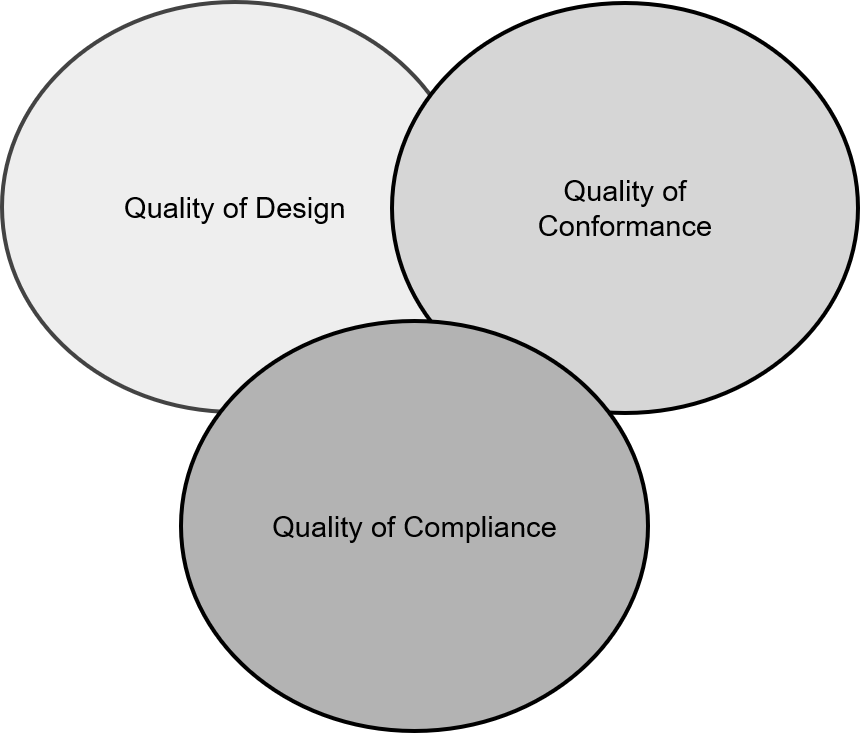

Direct material purchasing starts with quality. Parts and material definition start with precise specifications–new product launch and lifecycle design. Product Lifecycle Management (PLM) solutions–Recipe Management, Product Configurators, and Master Data Management–form the backbone of these systems. Quality of Conformance solutions measure and track deviation from specifications in manufacturing/sourcing and are critical for supplier development/management. Manufacturing Execution Technology Stack with an overlay of a Supervisory and Control Data Acquisition (SCADA) system measures and controls variability. The goal is to drive quality within standard deviations and improve the consistency of operations. In parallel, new solutions to address Quality of Conformance are evolving. These new approaches measure variations in supplier delivery, commitments, and response. In many ways, the world of inbound supply is like the wild, wild west. Purchase orders change on average three times before fulfillment, configurations change, and a continual need to improve lead time reliability. While the taxonomies are unclear, and the solutions are industry-specific, measuring the Quality of Compliance is a consistent thread for solutions like Elemica, Jaggaer, LeanDNA, SourceDay, and TraceLink. Direct procurement is an area where we cannot paint within the lines of existing taxonomies.

My Ask

I ask for all supply chain professionals to approach technology implementation with an open mind. Please do not put your energy into making current engines faster. Instead, continually ask three questions:

- How do the flows of existing technology architectures support (or not support) our current business?

- Where are the gaps?

- How can I use new technologies to improve business results?

When you do this, step away from the crazy lingo of “we need an end-to-end solution to improve supply chain planning.” Think about my lunch discussion with a bright and capable data scientist with wasted efforts in his current position. Don’t accept that existing taxonomies are the answer for today’s variable world facing the business today. Push harder to find new solutions to drive value. In short, lead your organization and give them the courage to paint outside the lines.