“Lora in your own way, you are helping. You tell it straight. You are pissy and opinionated in this world of supply chain blandness. I find it refreshing.”

Quote from a reporter this morning

The term supply chain excellence is easier to say than define. It permeates corporate strategy, but it lacks definition. I have been trying to define it as a supply chain analyst for over fifteen years. For some strange reason, it is a passion.

As a veteran of the go-go days of the hype cycle of Advanced Planning, I advocated that better planning improves corporate performance. As an analyst in the market for the past ten years (first with Gartner, then with AMR Research, followed by my work at Altimeter Group and now with my own firm Supply Chain Insights), I have stood in front of clients doing strategy days advocating “best practices” and I wanted to set the record straight.

When I wrote the book Bricks Matter, I wanted to write a celebratory book on why the adoption of new technologies and practices in supply chain had improved corporate performance. But the data could not support the promise. I wanted it to be data-driven. I had spent the last two decades in the technology market and I wanted to celebrate success. I could taste it. There is too much “yada yada” in the market. (I laughed at the quote this morning…)

So, I built a database of 20 years of supply chain financial ratios to try to find the correlation between the adoption of new technologies and the improvement on corporate performance, but I could not prove my hypothesis. Instead, what I observed when I looked at the data, was that most companies that I had worked with (in my role as an industry analyst, I had worked with over 300) were going backwards on margin and inventory turns. I found that nine out of ten companies were stuck. “Ugh,” I said. It was an awakening. As an industry analyst, in prior roles I had never had access to this data. We had always talked about the promise, but not looked at the reality. I believe that companies made progress in projects and drove short-term progress, but that it could not be sustained. I also believe that the rise in complexity eroded many results. (The rise in complexity happened faster than supply chain leaders could improve supply chain performance.) My question was, “What do I do now?”

I believe it in the toes of my feet and the DNA in the cells of my body, but I wanted to prove it. So, this has been my two-year mission. It is my quest.

The Supply Chain Index

Yesterday, I published a report on the first piece of my definition of the Supply Chain Index which we will launch in April. This work is based on a collaborative project with Arizona State University. In this work, we have taken supply chain financial ratio data for all publicly held companies and analyzed the data for strength, balance and resiliency. In the Supply Chain Index, each publicly held company will be given a mathematically determined number for their performance against their peer group (NAICS code) for strength, balance and resiliency. The formula is:

Supply Chain Index= Strength Ranking + Balance Ranking + Resiliency Ranking +Peer Group Assessment

Strength will be defined as year-over-year performance at the intersection of Growth, and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). Balance will be the ability to manage a portfolio of supply chain ratios to maximize market capitalization. Resiliency is the pattern at the intersection of operating margin and inventory turns. Strength, Balance and Resiliency will each count 30% of the total index with the peer-valuation counting 10%. The members of the Shaman’s Circle will weigh-in on the peer rankings.

I am looking at the data for 2000-2013 for several reasons. First, it is based on the belief that supply chain excellence takes many years. In the words of Marty Kisluik of FMC, “It takes at least three years to see results and five years to make it stable.” I heard this time-after-time in my interviews for the book Bricks Matter. I am hearing it again in my interviews for the book Metrics That Matter.

It has been a two-year research effort, and we are not done. We have had a lot of twists and turns, and lessons learned. We have stubbed our toes. One of my biggest lessons is that the devil is in the detail. It requires collaboration with great math minds to remove outlier data points, eliminate bias and ensure that we are applying the most current methodologies to the problem. I have loved working with Dr. George Runger and his team and give thanks to Mani Janakiram of Intel for introducing us, and for giving me some candid feedback that we needed deeper analytics help to complete our mission.

Defining Resiliency

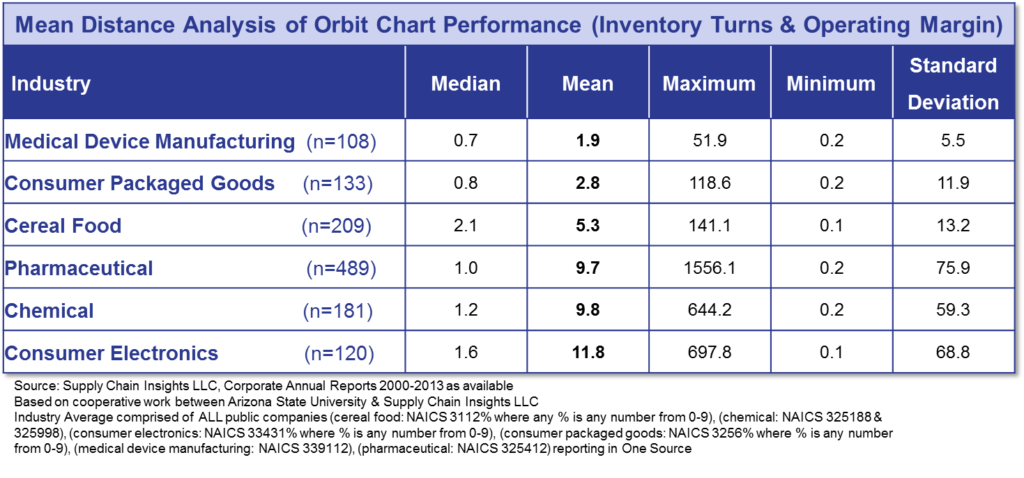

Yesterday, I published the report on Improving Supply Chain Resiliency. I define the resiliency measurement as the tightness of the pattern at the intersection of operating margin and inventory turns for the period of 2000-2013. My question for the Arizona State team was, “How do I best define a technique that can represent the randomness of this pattern?” I could see that the patterns were very random for some industries and not for others; and I could also see that the pattern was better for companies that I believed were supply chain leaders. My question was “How can I apply a methodology that would allow companies to measure resilience?”

The ASU team considered many different techniques and decided on the use of “mean distance” between each of the points over the period of 2000-2013.

Why is this important? Supply chain leaders want to deliver excellence. They are searching for an objective measurement that helps them to define “what good looks like.” They are a competitive group and want to track their own performance. I believe that supply chain leaders are charged with the delivery of consistent and reliable results at the intersection of operating margin and inventory turns, and most companies are not very reliable.

A Closer Look at Resiliency

Industry performance on resiliency is quite different. As you look at the data, consider how foolish it is to put all industries in a spreadsheet and shake them up. The data sets are quite different in both the mean, the range and the standard deviation. As shown in the data below, the most resilient industries are medical device and consumer packaged goods. And, as shown in our prior reports, the variation in contract manufacturing and third-party logistics providers should be a stay-awake issue for companies worried about corporate risk.

I think that the marked resiliency between Samsung and LG Electronics is due to supply chain excellence. Samsung outperformed LG on operating margin, inventory turns and resiliency; but they are not comparable to P&G. The industry drivers are just too different. I also see it in the data between Stryker and Boston Scientific, Merck and Shire, Walmart and Target; and between Colgate and Unilever. But, I want you to see it also. For more on our analysis of resiliency, please refer to our recent report. Meanwhile, we will continue to define supply chain excellence, one column at a time.

So for readers that are holding your breath waiting for the Gartner Top 25 report in May, I would advocate that you start breathing deeply again, and reconsider the approach. The more that I work with the development of the Supply Chain Index, the more flawed that I can see that the work that I did at Gartner was…. I am embarrassed that I was ever a part of the methodology. I am also convinced that the supply chain leader needs a methodology that is:

- –Widely Applicable. A methodology that can be applied to ALL publicly held companies. The Gartner Top 25 only looks at the Global 1000.

- –Industry-specific. A technique that evaluates each industry. I firmly believe that you cannot put all industries in a spreadsheet and shake it up. I think that each industry needs to be evaluated separately.

- –Longer-Term in Focus. I wanted a view that was longer-range view than three-four years. My reasoning is that it takes many years to drive true supply chain performance.

- -Encompassing. More encompassing of metrics beyond the growth, inventory and Return on Assets (ROA) metrics used in the Gartner Top 25. I think that the supply chain leader needs to drive strength, balance and resiliency against a business strategy.

- -Objective. The Gartner Top 25 ranking has a high percentage of input coming from analysts and peer group rankings. While I do not know what it will be this year, in the past, the analyst ranking and the peer scoring have been 40-50% of the score. As a result, it becomes a popularity contest.

It is for this reason that I will continue my quest. I hope that you will join me to hear about the findings. We will be presenting the overview of the resiliency rankings on our webinar on April 24th and the complete rankings at our Supply Chain Insights conference at the Phoenician on September 9th-11th. If you would like to get the rankings for your company, just drop us a line. We look forward to helping you on your journey. I just think that we need an objective measuring stick.

For my prior views on the Gartner Top 25 and the work on the Index, please check out these posts:

What About the Supply Chain Index

Will Arrogance Stunt your Growth?

What I have Learned Working on the Supply Chain Index

Why I No Longer Believe in the Gartner Top 25