In my writing, I try to get clear on definitions. The supply chain space is heavily laden with acronyms, gobbledygook, false narratives, and over-hyped, fast-talking technology sales teams. Let’s take an example. This is a post from LinkedIn today. “At the Digital Supply Chain event at SAP. First great insight from John McNiff: digital mature companies have lower DIO, IBP supports them!” My question is, “What is a digitally mature company? And, how does IBP support them?” When I asked the question, I got an answer from LinkedIn that the research focused on digital maturity with SAP. The research is generated by SAP. I am still waiting for an answer on what this means.

Let’s take another example. Here is a comment, “Hi Lora, I found your Birds of a feather post interesting, but I don’t agree that there are no end-to-end solutions out there. I have built five such systems for companies. I am a consultant, and I am meticulous in implementations. I do not have a website and have not updated it in more than ten years. I just went live this year with a Fortune 25 company, and their factories book against their orders online. “

Or, “Lora, you say that there are no end-to-end solutions, but I have built and implemented many.” Followed by, “We just implemented an end-to-end solution at Unilever; the results are impressive.”

Traditional View

What does end-to-end planning mean? The term is used frequently, but I find that it is often tossed into the air like a carrot in a tossed salad and then mixed with dressing. It may look and sound good, but what does it mean? Is there value?

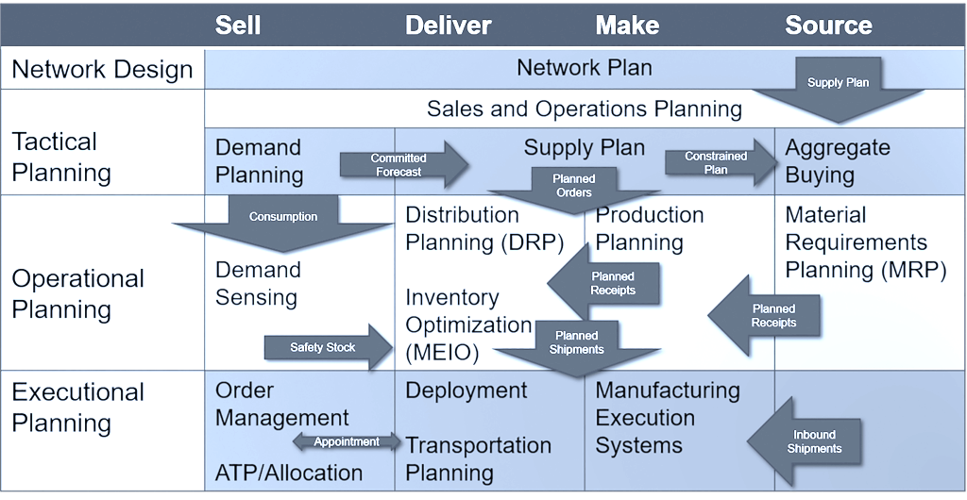

Traditionally, the definition of end-to-end supply chain planning meant:

- Forecasting based on order or shipment patterns.

- Forecast consumption into supply planning based on rules (rules-based-consumption).

- Translation of the demand forecast into planned orders to minimize manufacturing constraints.

- Use of optimization to consume planned orders into manufacturing scheduling and distribution requirements planning (including inventory optimization of safety stock).

- Matching demand and supply in Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP).

- Use of order patterns to execute a route guide in Transportation Planning (TMS)–route planning, pooling of less than truckload, and load tender.

In this traditional definition of a supply chain model, I define a good plan as:

- A positive Forecast Value Added (FVA) analysis/output for the forecast with minimal bias. (I do not define it by error.)

- Feasible plan for tactical manufacturing planning (outside of lead time) reflecting actual constraints.

- Plan adherence in production scheduling.

- First pass tender percentage in transportation planning.

In the process, few companies define what good looks like.

Be careful about the gaps. Please note that in the traditional definition of supply chain planning, demand planning does not synchronize with revenue management (they operate as separate entities), and transportation planning has nothing in common with distribution requirements planning. And, there is no translation of planned orders for manufacturing into aggregate procurement. (MRP is translated based on the manufacturing schedule into ERP.) Channel data is usually located in the sales account teams, not used by the supply chain team. So, is it really end-to-end? I think not, but I will leave this up to you. I think that there are many black holes. The focus is on functional optimization. There is no balanced scorecard to align the functions.

This is the traditional software taxonomy that drives the definition.

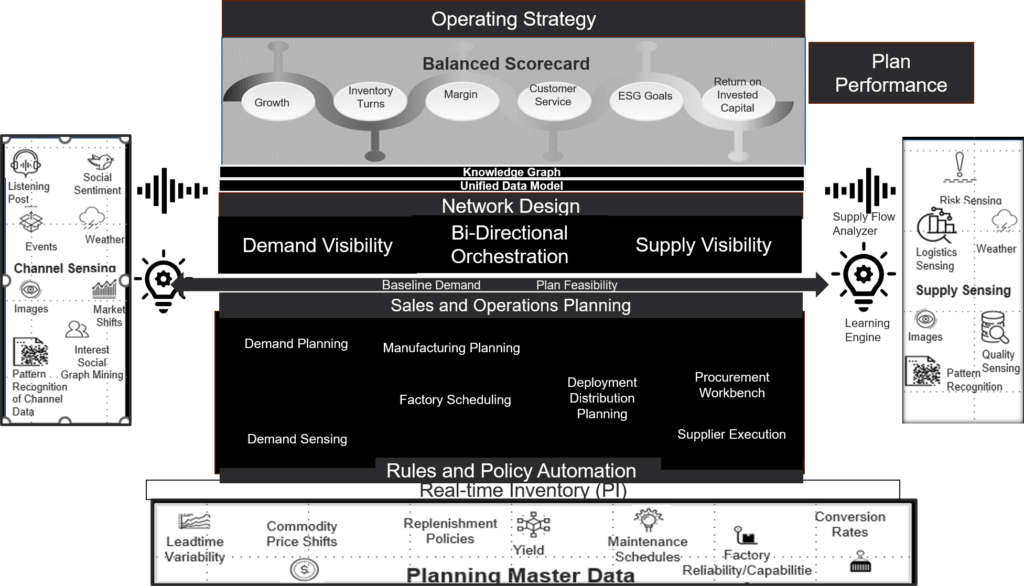

Outside-in Definitions

The scope changes in the redefinition of supply chain planning for outside-in processes. The focus is on the use of market data and sharing data across the functional silos of sales, marketing, finance, operations, procurement, and transportation. The new definition is the improvement of decisions based on insights through the bidirectional analysis of demand and supply flows from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier. The order is only one of 15-20 inputs. The analysis is bi-directional and tethered to a balanced scorecard. The focus is less on integration to transactional data and more on insights and orchestration of decisions across make, source, and deliver with a focus on trade-offs.

This is the taxonomy used in the testing.

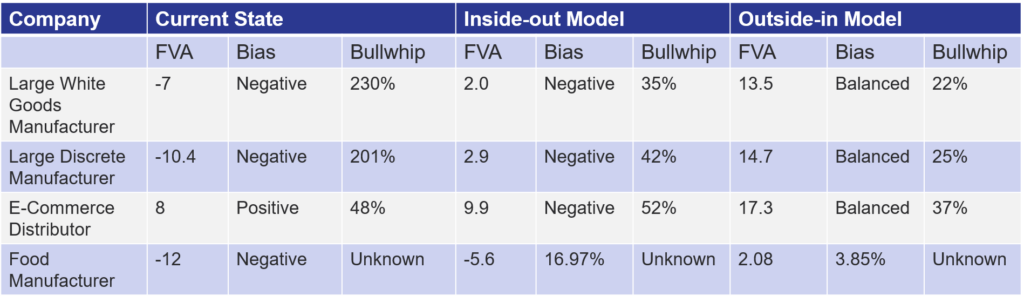

In the testing, using the outside-in data improved Forecast Value Added (FVA), the decision’s bullwhip, bias, and latency. We are continuing the testing in January, but no inside-out model beats an outside-in model so far. While most companies focus on better engines (math) the secret is the redefinition of the model and the data set.

So, the next time you discuss supply chain value, be clear on the definition. Words without meaning are simply that: they have no meaning.