My Quest To Redefine Planning

The focus of many discussion threads on LinkedIn this week focused on building better engines for planning. The discussions included the pros and cons of probabilistic versus deterministic optimization, advancements in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Deep Learning, and improvements in Machine Learning. I get it, and the geek inside of me loves the engine discussions, but I firmly believe that better engines in an old-fashioned jalopy get us nowhere. Let me explain.

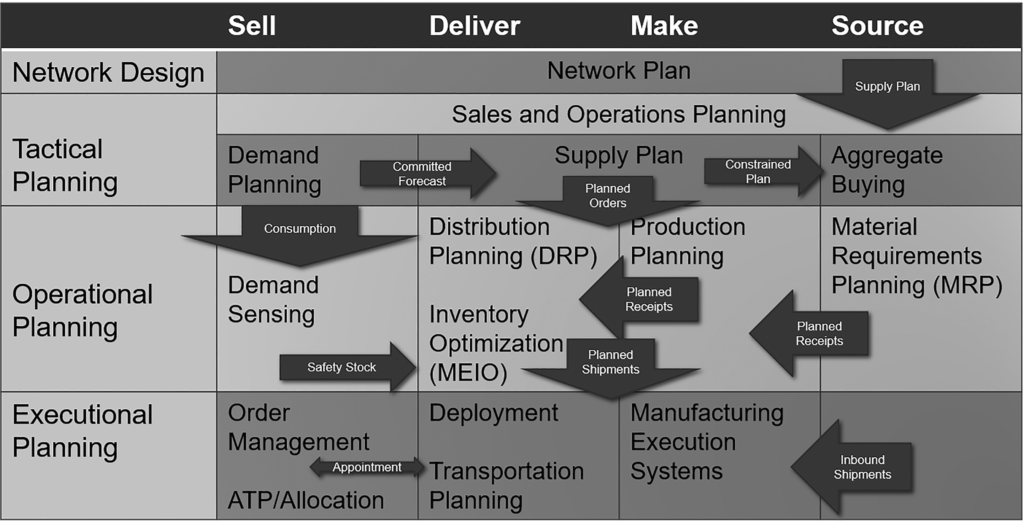

In Figure 1, I share a supply chain planning taxonomy or what I lovingly term an old-fashioned jalopy. Each box has an optimizer that drives output from a model based on a functional definition using enterprise data. There is no unifying data model; all items are treated equally, regardless of the flow. The flows between the boxes (or optimizers) are based on consumption logic that increases the bullwhip effect. Few companies design their supply chains (research data shows that 9% of companies actively design their supply chains), and few planning systems actively analyze and drive answers to the questions:

- Do I have a good plan?

- Is the plan feasible?

- What is the data and process latency in current decisions? What is the offset from the market? Am I able to make a decision at the speed of the market?

Figure 1. Conventional Planning Taxonomy–An Old-fashioned Jalopy

The current framework for supply chain planning, built in the 1980s, uses the output of the demand plan to drive better decisions in three areas:

- Determine the appropriate level of safety stock

- Plan replenishment (DRP)

- Define planned orders for Manufacturing Planning (MPS)

I firmly believe that focusing on these three areas, or seats in the Jalopy, is insufficient. The demand must be embraced as a flow, not an analysis of time-phased data, to drive better insights. Planning needs to respect the multiple flows of items–high volume and predictable, low volume and predictable, low volume and not predictable, seasonal, new product launch introductions, and demand shaping. Supply needs to align with the flows.

So, you might say, “Lora, why does this drive you to ride an octopus?” My goal is to redefine the supply chain planning space to sense and respond using outside-in data. Bear with me a bit longer, and I will explain. The current taxonomy (or frame/models) for the engines does not address the issues of the global multinational manufacturing company. Here are a few of the gaps.

- In the Global Supply Chain, there are More Constraints To Address Than Just Manufacturing. With the rise of logistics and procurement constraints, an analysis of only manufacturing does not yield a feasible plan. Companies need a planning solution to analyze the trade-offs between make, source, and deliver. I term this bi-directional orchestration. This does not exist in conventional planning frameworks.

- MRP Alone Is Not Sufficient for Procurement. Procurement planning inside of lead time is not sufficient. While DDMRP improves the logic of MRP within lead time, there needs to be a tactical procurement workbench (operating in the time horizon outside of lead time) to analyze the alternate supply, bill of materials, price structures, impact on ESG commitments, and platform requirements (impact on complexity).

- S&OP Is Over-Played. Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) is no panacea for the lack of clarity of an operating strategy or the absence of product flow design. The global supply chain is very political and lacks a unified data model at the planning level. (For example, DRP and TMS have nothing in common, and revenue management (price or promotion management) does not connect to demand planning.) Without clarity on the operating strategy and alignment of models, it is very difficult for companies to make decisions.

- A Focus on Safety Stock Is Too Narrow for Effective Inventory Management. My inbox is full of articles on probabilistic planning to improve safety stock. My response is a big YAWN. The reason? A manufacturing company’s safety stock is 30-40% of the total inventory requirement. The form and function of inventory need to be addressed holistically, and this requires much, much more analysis than probabilistic forecasting. (The form of inventory for a manufacturer includes the analysis of in-transit inventory and cycle stock which usually have larger impacts than safety stock in a manufacturing company.)

- Need For A Planning Master Data Layer. Most planning systems are installed with a “set it and forget it” mentality. Lead times, price, and conversion rates constantly change in the market and are not reflected in optimizers’ re-runs. As a result, outside-in planning includes defining a market-driven master data layer.

- Market Driven Insights. Orders and shipments are poor proxies for actual market demand. As a result, innovators build market insights and define models to use market drivers.

I could go on and on, but let’s leave it here. I count 30-35 gaps.

So, What Have I Learned? Why Am I Now Riding An Octopus?

Let me share some history. During 2020-2022, I worked with 09 in Project Zebra to test and learn how graph database frameworks can embrace/define demand flow. The testing showed great promise, but o9 stopped the testing at the end of 2022. The reason? The market is clamoring for better engines in an old jalopy. With the failure of ERP vendors to build robust planning solutions to answer the needs of manufacturers during the pandemic, the market shifted to drive share to three best-of-breed providers Kinaxis, o9, and OMP. (These are three very different solutions.)

I have now trained Kinaxis, o9, and OMP teams on the concepts of outside-in planning, but I question the future. Each company is busy–swamped with client commitments to drive faster in the old jalopy while dancing at the Gartner conferences under the halo of the Magic Quadrant. Supply-centric focus reigns with customers asking for control towers, risk management solutions, and learning engines. Few manufacturers understand that the frame of the jalopy is broken and that investments in control towers and risk management drive a reactive knee-jerk reaction because we are not decreasing the bullwhip effect, aligning to a balanced scorecard, and changing the impact of poor planning.

I value my learning from the work. There is no safe space for technologists and business leaders to innovate together. I commend o9 for building that space in 2021-2022. It is hard for manufacturing organizations to work together with technologists under the vice grips of the technologists’ current sales/marketing processes focused solely on pipelines.

The biggest challenge in the testing with the technology providers was driving unlearning. Technology providers are harder to work with than business leaders in unlearning, and consultants are the worst. Each wants to chase business leaders trying to drive new engines in an old jalopy. The market has a lot of hype, jargon, and hand-waving but very little testing. <SIGH>

What is the value of planning? Most companies do not use their systems, and there is a lack of clarity if the investments truly drive value, yet we continue. There is a reason why Excel is the number one planning solution.

Why is the work hard? Most technology companies’ identities are based on the knowledge of traditional supply-centric processes. Challenging the definition is uncomfortable in a surging market, and no consulting company leads the effort. However, the planning market is cooling, and the new entrants–like Garvis, Ikaigi Labs, and Palantir–will challenge today’s companies. The evolution of NoSQL and AI offers new opportunities to eliminate the jalopy. The discussion of engines will shift to the evolution of applications; and, hopefully, then to the building of new frameworks.

The basis of Project Zebra is the question, “Can Business Leaders Change Their Stripes to Embrace the Advantages of the Art of the Possible?” My answer is no, not easily. For a better understanding, check out the book on Project Zebra principles that focus on unlearning.

So, why ride an Octopus? I decided, based on the difficulties of training and changing the mindset of technologists, that I needed a new metaphor to speak to manufacturers. Through debate with a designer, I landed on the concept of an Octopus. My goal now is to continue to drive the concepts with manufacturers and then bring the innovative manufacturers to the technology vendors for testing. Metaphors help.

Why am I doing this? I believe even this hard-headed old gal just cannot break through the obstacles of driving change in traditional sales-driven technology companies.

Let’s examine why I think an Octopus is a good metaphor for the work:

- Adapt and Learn. Octopuses have eight arms. Each arm has its own ‘mini-brain.’ The intelligence is decentralized but governed. Action: Supply chains have different functions that need to work together, but today, there is no way to decentralize and centrally govern decisions. Current technologies enable functional decisions based on efficiency. In outside-in process definitions, leaders understand the need to clearly define an operating strategy and define a balanced scorecard to drive better decisions. Governance is clear, and outcomes are measured using new forms of technology.

- Sense and Respond. An octopus has around 500 million neurons. Two-thirds are located in its arms. The rest are in the doughnut-shaped brain located in the octopus’s head. As a result, they are agile, able to sense and respond to a series of complicated and tricky tasks. Action: Supply chain leaders understand the need for market data (outside-in processes to use data from customer channels, suppliers, logistics, and market shifts) to improve sensing to drive an intelligent response. The focus is on continual learning based on insights from outside-in processes.

- Builders. Octopus builds congregations of dens from rock outcrops and discarded piles of shells from the clams and scallops the octopus feast. The ecosystem enables life. Action. The supply chain leader builds effective networks from the outside in to drive market-to-market processes. The builder works hand-in-hand with suppliers and customers to share data, sense, and drive an intelligent response to decrease the time to act.

- Heart. The octopus has three hearts. Two of the hearts, called branchial hearts, are located near each octopus’ two gills. They pump blood through the gills. The third heart (called the systemic heart) then pumps the oxygenated blood through the rest of the body. Action. The supply chain leader expresses heart for the customer, their trading partners, and their employees using a definition of functional excellence (their arms) to adapt and serve while guided through an over-arching governance model. Sensing outside-in drives multi-tier insights to enable information about trading partners to pump through the organization based on the sensing and transmission of data from the demand and supply networks.

- Vision. The octopus has strong eyesight. They have a clear vision of their surroundings and the action to take. Action. The supply chain leader invests in technologies and data services to enable proactive insights and a clear strategic vision. They know reacting is not enough; the teams align continually to improve outcomes. The enabled leader knows that it is not enough to see data; the enlightened supply chain team knows they need to use analytics to drive action at the speed of business.

So, net/net new engines in an old jalopy are not the answer. We need to redesign planning to sense and respond outside-in. The framework redesign is a great opportunity for an ontological framework in combination with a graph to deliver on the Octopus metaphor. Then, and only then, should we have a discussion on engines.

What do you think? Want to ride the octopus and test and learn with innovators? If so, drop me a note.

It might take me a few weeks to respond; I have major surgery on Monday. Take care.

Recent Podcasts:

Want more insights? Check out recent podcasts.