Surgery is over. I am safely recuperating at home. Due to travel restrictions, I cannot attend many industry events, so I observe from home, watching webinars and remote broadcasts.

As I process the content, I struggle. My mind questions, “How did we get here?” I believe that the industry is stuck. My question is, “How do we break the conventional norms to drive breakthrough thinking?” The industry is in a groupthink, largely missing the opportunities for breakthrough innovation.

Managing the Contrarian Deep Inside Of Me

It is hard to manage the contrarian deep inside of me. With more than forty-five years of experience in the industry, I struggle with the lack of progress and the current level of Groupthink. Many of the case studies being presented at today’s conferences were born during the pandemic and the post-pandemic turbulence. While companies talk digital, the projects follow traditional supply-centric paths. As I listen, I struggle. As you read this blog, I hope that you will see me as a positive contrarian versus an old curmudgeon. Before you react, here are some definitions.

Contrarian: A person who habitually takes a view opposite to that held by the majority.

Curmudgeon: An ill-tempered (and frequently old) person full of stubborn ideas or opinions.

Wikipedia

Unleashing the Contrarian

Here are my thoughts this morning over coffee:

Gartner Top 25: Really A Celebration of Supply Chain Leadership? While I was preparing for surgery, Gartner released the Gartner Top 25 Analysis. Designed to lift the profession and celebrate supply chain results, I struggle to find that the methodology supports either objective.

The analysis is now in its ninetieth year. Almost two decades of reporting. But does it help the profession? My vote is “no,” and I hope to convince you of the same.

The Gartner analysis is biased toward companies within the Gartner network. For example, the Gartner Top 25 celebrates the accomplishments of Intel (active with Gartner), but in the analysis in Table 1, Nvidia Corporation and Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) clearly outperform Intel in the Semiconductor Industry. Neither Nvidia nor TSMC makes the Gartner list. The reason? They are not active in the Gartner network.

Table 1. Semiconductor Industry Analysis

Would you feel better about your results if you were Intel or TSMC? Or Nividia? The entire industry sector analysis (Table 1 is a small part of the total analysis) clearly shows that Intel is a laggard. Yet, Intel is listed as number sixteen on the Gartner Top 25. Laughable, right? I would laugh if it were not so sad and damaging to the industry.

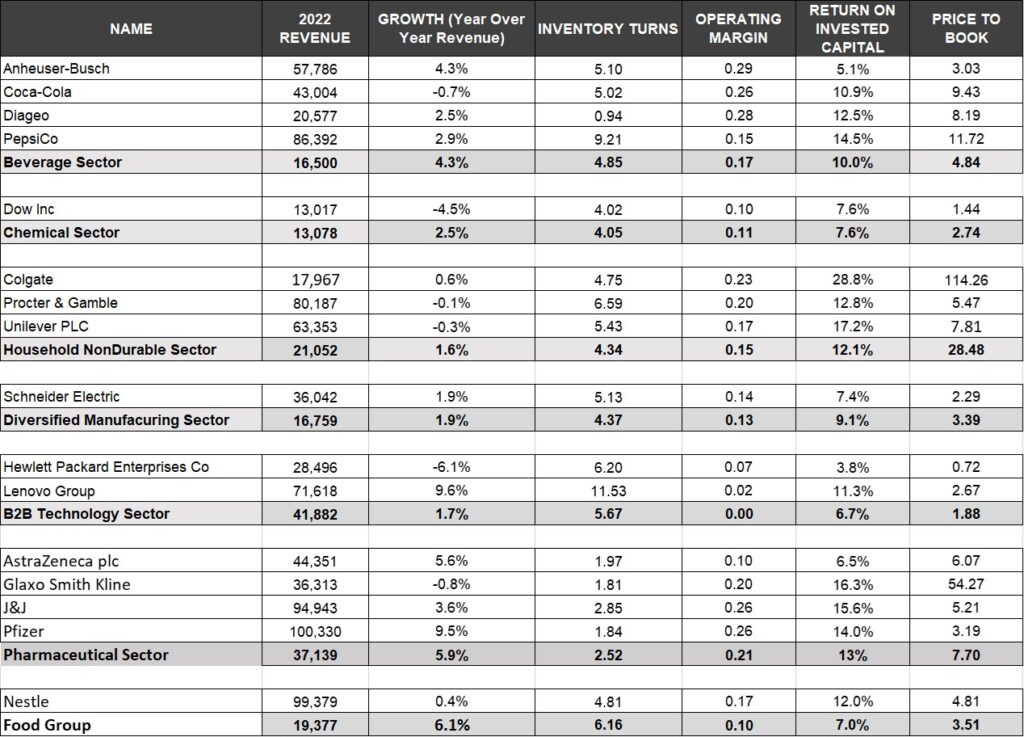

One of my insights from doing the industry analysis for the Supply Chains to Admire each year is that smaller and less well-known companies outperform larger and better-known manufacturers. While companies that supply chain leaders believe are top performers– J&J, P&G, and Unilever– do not outperform their peer group. To support this assertion, I share the results in Table 2, which contrast the Gartner Top 25 2023 winners to the results of their industry sector for the ten-year period of 2023-2022. I list sixteen in Table 2, but of the 29 companies listed in the Gartner Top 25, 27 underperform their peer group sector. Is this success? I don’t think so.

Table 2: Gartner Top 25 Comparison to Peer Group Results

As large manufacturers work the conference circuit in the industry to increase brand awareness for their supply chain efforts, they feed the perception that their stories demonstrate supply chain leadership. However, in the process, no company is held accountable for a performance standard, and as a result, we are learning glossy versions of stories from laggards.

The audience assumes that the presenting company is outperforming. For example, you will never find P&G or Unilever taking the stage to discuss why they underperformed in growth over the last decade or Lenovo discussing why they underperformed against their peer group in operating margin. (These would be great discussions. We do not do enough learning from failure.) However, no company wants to share insights from failure.

So, regarding the Gartner Top 25, industry perception is not reality. We find that the companies with the most marked improvement in a balanced scorecard of growth, inventory turns, operating margin, and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) are smaller and less well-known. They are not active on conference circuits. The companies are not active in Gartner networks. As a result, they will never make the peer or industry peer review analysis for the Gartner Top 25 ranking. (The analyst ranking in the Gartner Top 25 represents 25% of the score, while the industry peer analysis is 25%. As a result, 50% of the ranking is industry perception.) For example, Monster Beverages beats Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, while Celanese outperforms Dow Chemical.

A gap in the Gartner analysis is the lack of a sector or industry analysis. All companies but two– Apple and L’Oreal– listed in the Gartner Top 25 underperform when compared against their industry peer group for 2013-2022.

The analysis is biased toward large process-based manufacturers in the Gartner network. As a result, the analysis overstates company performance in process industries like pharmaceuticals and understates the results of heavy discrete contributions in airspace and defense, apparel, diversified manufacturing, trucks and heavy equipment, and retail.

My lessons learned from doing ten years of analysis include the following:

- Lack of Supply Chain Economies of Scale. Smaller companies outperform their larger counterparts. We have not achieved supply chain economies of scale. The larger the company, the more likely they will underperform against their peer group.

- Leaders of the 90’s Are No Longer Leaders. The regional manufacturing-centric models that defined earlier leaders like P&G and Kraft-Heinz are obsolete. Today’s leaders tend to be better aligned across their organization with their customers, and the company has strong horizontal and balanced processes (new product launch, Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP), and supplier development).

- Learning Stalled. While large process manufacturers are held up as the industry standard, many underperform. As a result, the lessons given in case studies and at industry forums do not help the industry progress. We must rethink our leaders based on performance data and begin holistic learning.

A Focus On Risk. Why Not the Balance of Risk and Opportunity? Today’s risk management solutions focus largely on supply sensing and early alerting. Some solutions now include proactive event management driving recommendations to correct/prevent disruption. Watching the presentations, I wonder how we became so laser-focused on such a limited view of risk. I also ask, ” Why is there no balance of opportunity versus risk?”

I smile as I work on data for a client where the greatest risk is demand. The company’s focus on item proliferation resulted in 40% of items moving into a non-forecastable category. Since the company does not measure forecastability, the team continued to use traditional methods for forecasting, increasing the bullwhip effect and driving internal supply chain disruption.

Which brings me to the question, “Shouldn’t we balance risk with opportunity systemically?” And, “Why are we only discussing supply risk versus analyzing demand and channel risks?” For example, with the pending recession, I worry that many companies will lose first-mover advantage in pricing. Companies that operate separate systems for revenue management and demand management create a risk in understanding market trends and gauging price elasticity quickly.

With the increase in product complexity, many companies have demand latency longer than supplier lead time. (Demand latency is the time cycle to translate a channel purchase to an order.) The increased demand latency and required cycle stock are risks from unabated complexity, yet, few companies are attacking product rationalization.

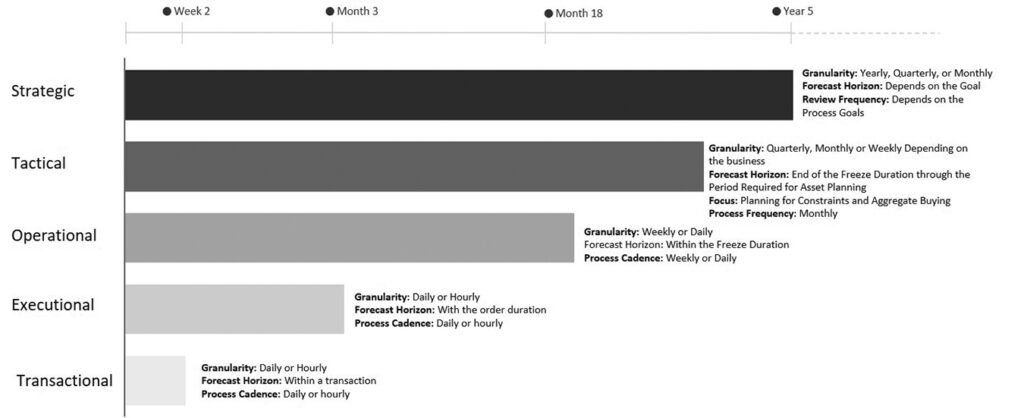

Why Do We Believe Reactive Planning Processes Are Beneficial? Most of the presentations I view celebrate reactive behavior in the operational and order execution horizon. I hang my head as I see the many presentations on control towers and digital transformation. The control tower presentations are primarily centered on driving a reactive response, while the digital transformation presentations are largely hand-waving.

I ask, “What happened to the better design of supply chains and the bi-directional orchestration of constraints across source, make, and deliver outside of lead time (the tactical horizon)?” Note: The greatest benefits in order reliability and margin occur when flows are managed in the strategic and tactical horizons. During the last three years, companies have become more reactive, focusing more on the operational and executional planning horizons. This trend leads to reactive behavior. I fear we are losing a basic understanding of supply chain planning with employee turnover.

Figure 1: Definition of Planning Horizons

Wrap-up

The supply chain planning technology space is ripe for disruption. Over the last seven years, the failure of the SAP APO migration to SAP IBP and the general deficiencies in ERP planning solutions gave headwinds to the best-of-breed supply chain planning market. The greatest beneficiaries were Kinaxis, OMP, and O9. (These are three very different solutions.) Will these solutions disrupt? I would love to think so, but the teams are incredibly busy, and it is easy for these technology leadership teams to attribute success to their work, discounting the market drivers. So, I constantly ask the leadership teams at Kinaxis, OMP, and o9 to tell me how much of the 2022-2023 revenues are due to their success versus the general failure of SAP IBP? The answer is unknown, but I attribute more to the market drivers than they do. Each company is focused on improving the engines within existing planning taxonomies. Each is sales-driven following prospect requests and classic sales cycles.

Will the disruption occur from the increase in venture capital spending? I would love to think so, but I find transactional thinking and a low-level understanding of supply chain planning by venture capitalists in most of these discussions.

Could SAP mobilize to redefine the space? Maybe, but I don’t see the leadership.

The interjection of AI innovation is a positive, bringing new thinking to the technology landscape. My bet is on the emerging tech. If you are a technology leader, watch the evolution of the new tech closely. As it evolves, prepare your teams to test and learn. In the process, challenge your planning group to unlearn and be ready to redefine work. Challenge convention—the traditional definition of supply chain planning is passee. We don’t truly have end-to-end solutions for supply chain planning (there is no unified data model across functional planning solutions like Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP), Material Requirements Planning (MRP), and Transportation Management Solutions (TMS)), and the goal of demand applications should extend past supply consumption to help organizations decrease demand latency, reduce the bullwhip impact, and align flows to improve rules-based order fulfillment.

I love the concepts of outside-in planning, but these are slow to evolve. In late summer, I will teach an open class on the principles and the test cases to date. Look for this announcement in July.

Take care and enjoy the summer. And thanks for listening to the voice of a contrarian as she recovers from surgery. I hope that I don’t come across as a curmudgeon. I look forward to getting your thoughts.