This week I spoke at the Chicago CSCMP roundtable event. I love to hear the thoughts from different speakers. At the event, James Rice from MIT spoke on innovation and his reflections on Clayton Christensen’s 1997 classic business book, The Innovators Dilemma. I, like many of you, read this book when it was published. However, hearing the concepts again from Jim sparked some new thoughts.

The premise of the Christensen’s book is when companies focus on current customer needs they fail to adopt new technologies or business models that will meet the customers’ unstated or future needs. This is disruptive innovation. Kodak was a victim in the film industry. Digital replaced film for photography. I think that IBM, HP, Microsoft, Oracle, SAP and Teradata are victims today in the information technology sector. Amazon, Google, and Uber are new commerce platforms.

Christensen’s concept is that businesses will reject innovation based on the fact that the customer cannot currently use the innovation, delaying the adoption of great ideas. The spark from Invention to Innovation is slow. It requires the early adopter and visionary.

Reflections

In my role as an industry analyst I have been lucky to attend many great conferences and hear wonderful speakers. One of my favorite speeches over this 15-year tenure was listening to Alan Greenspan at the AMR Research IT conference in November, 2006. At the time Alan was frail. He spoke from a chair in a stilted voice with an uneven tempo. There were no polished slides, but his words were brilliant. They remain with me.

Alan spoke of the impact on business economies with the adoption of technologies. He discussed the adoption of the steam engine and the electric motor in the manufacturing sector. Today, we take these technologies for granted; but, the electric motor was the genesis of the horizontal manufacturing plant. Prior to the concept of the electric motor, gravity moved materials and factories were vertical. The differences between labor productivity in a horizontal versus a vertical factory configuration were dramatic; however, the adoption of the electric motor took over ten years.

In my travels in cities I sit in the backseat of many a taxi cab, looking at the landscape of vertical and horizontal factories, and think about the adoption of the electric motor. As I move past the factories in the car, it makes me think about the adoption of supply chain planning.

My Journey with Supply Chain Planning

My journey with supply chain planning started quite innocently. I was running a factory, and I made a bet with the production team that I could schedule the lines through a heavy summer period and predict production needs adequately to predict when they could get weekends off to spend with their families. If I won, they would cook me dinner. If they won, I would cook it for them. I built a macro on a spreadsheet to manage cycle stock. I used history to predict the future. Things were simpler then. It was 1988. It was a regional business with a limited product line, and I successfully won the bet using a spreadsheet. Spreadsheets are not adequate for the complex world of the global multinational.

Through this work, I was noticed by a supply chain planning firm. I was recruited to join Manugistics (now a JDA company) in 1990. At the time, I had never heard of a technology category of supply chain planning. As I read the literature I felt out of touch and old-fashioned. “How could I not know about supply chain planning software?” I thought. On the plane to my interview, I read everything I could about planning software and thought about the simple spreadsheet challenge that was the genesis of my journey. I wanted to catch up. I did not realize I was bridging two very different worlds: a world where the concepts of supply chain planning were a given, and the world where supply chain planning was an unknown.

The Manugistics team was an energized culture. Software planning was in the middle of a hype cycle. Those were the go-go years of glory for planning vendors. As a result, many implementations were over-promised, and under-delivered. The software category spun out of control with the rise and fall of supply chain planning software vendors. However, I survived 19 layoffs working at a software planning vendor in the first act of supply chain planning.

In the second act of supply chain planning—tightly integrated ERP to supply chain planning—I was an industry analyst. I worked first at Gartner Group and then at AMR Research. I was an avid student of supply chain excellence; and in this role, I watched as best-of-breed solution after best-of-breed solution was replaced with more complicated technology. I was a skeptic. We now know that the tightly integrated supply chain planning solutions are more expensive, with a longer time to value, and lower user satisfaction. However, we did not know it then. Millions of dollars were spent; but to companies’ dismay, supply chain planners still plan with spreadsheets. The second-generation systems were difficult to use, supply chain planner turnover was high, and the processes were inflexible.

I am currently working on an in-depth study on supply chain planning benchmarking (publishes in August), and working with the team to analyze supply chain planning adoption. I find it ironic that the supply chain leaders are quite confident in their abilities to plan, but the planners themselves are not. There is a gap. As I work on the data analysis, I cannot help but think about the electric motor and the adoption of new ways of working. Thoughts swirl in my head. I keep thinking, “Business innovation, and the rate of business change is happening faster than we can adapt. Technology invention is happening, but the translation to innovation is slow. This is especially true in large companies.”

I had a call today with a client that added fuel to my fire when he said, “We did a major re-implementation of supply chain planning three years ago. We made a mistake thinking that we would get the savings for the project on Day 2 of the implementation. It has taken us three years to learn how to plan. Our tools are not the best, but the organization’s capability to absorb planning as a concept has been a larger barrier.” I smiled. In my analysis of the supply chain planning benchmarking data, I can see it. It is pervasive. The traditional supply chain leader rewards the “urgent” and struggles with the “important.” Planners need time to plan. The organization must redefine work processes for a new way of working. It is important work that is not well understood.

I then think of disruption. The landline phone versus the mobile phone. Digital imaging versus film. The power of computing. The role of connectivity in the rise of the global multinational. GPS navigation. Our progress in adapting supply chain planning to business processes has been so slow, should we abandon evolution and consider new approaches. Can we afford evolution?

Adopting Invention and Driving Innovation in Supply Chain Planning

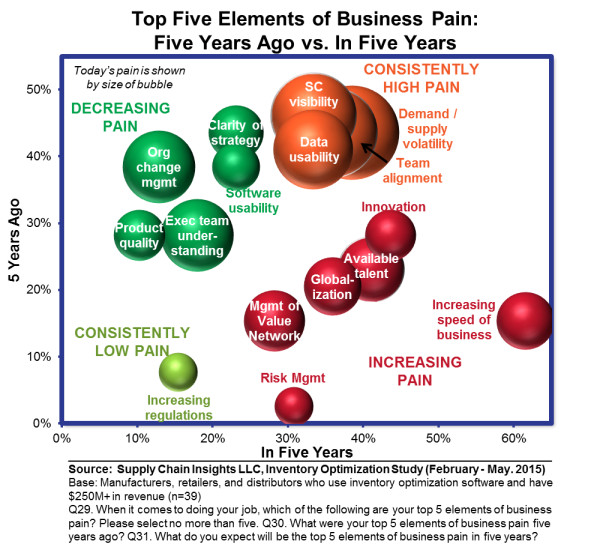

The pain, and the reason to change, is rooted in the business. In Figure 1 I contrast the drivers and trends from a recent study. It is a comparison of business pain for the past five years and future five years. Contrast the beliefs over the ten-year spread.

Figure 1. Contrasting View of Business Pain: Comparison of Past Five Years to Future Five Years

The size of the bubble represents the business pain. Note three trends in this research summary:

1) Demand and supply volatility is increasing. Most business leaders do not realize that with the increasing long tail of the supply chain that the forecastability—the ability to forecast the supply chain—is getting worse. As a result, we can push and push on forecasting processes and not drive improvement.

2) Executive understanding of the supply chain is a barrier. The evolution of supply chain processes are only 30-years old, and most executives lack the understanding of the supply chain. Without executive understanding it is almost impossible to drive cross-functional team alignment. Most companies are stuck in a very ‘functional view of supply chain.’ I define supply chain management as the processes from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier. This is a much broader definition than most organizations endorse. Today, 32% of companies have source, make, and deliver reporting to the same organization, and the gaps in alignment between operations and commercial teams are large.

3) The rate of change in business is accelerating. Note the far right bubble. The rate of business change is what worries me. It is the genesis of this article.

I then think back to Alan Greenspan’s discussion of the electric motor, and I think, “How can we accelerate technology adoption? What can we do to spark invention into innovation? Why are companies stuck in their planning processes?” I think that the traditional paradigms defining supply chain planning need to be questioned.

Invention into Innovation in Planning

Last night I spoke at a conference on the use of advanced analytic techniques and the future of planning. I was deep in thought. Supply chains do not play by the rules; however, our current systems are programmed to direct outcomes based on fixed, and inflexible rules. As a result, the systems cannot adapt.

Our current processes motivate planners to touch data. We encourage the building of Excel labor ghettos despite the fact that companies cannot adequately manage the nonlinearity of the supply chain as a complex system in an Excel spreadsheet.

So, I don’t think we move to the future through evolution. Instead, I think that we have to embrace new technologies as disruption and drive innovation. Can we use technology to plan and redesign work processes for planners to give us insights? Let me give you two examples of technology invention in demand sensing and how we could use it to drive innovation.

Most companies want to be demand-driven. They want to better translate demand into supply. I am convinced that we cannot get there through traditional forecasting processes and rules-based consumption in traditional Advanced Planning Solutions. My reasoning? Forecasting is a tactical process to look at a changes in the market over a long-term duration of months and years. It was never designed to be a short-term process to drive replenishment.

With the evolution of Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP), and the building of the first generation of integrated supply chain planning tools, a monthly forecast was chunked into daily requirements through rules (termed rules-based consumption). This design was driven by technology limitations in the software and computing processes in the 1990s. It was not an ideal design. As most people realize, the market is too dynamic to accomplish this through fixed rules. As a result, this logic is flawed. We can never get this right.

In 2003, a short-term forecasting approach using pattern recognition was invented by Terra Technology to replace rules-based consumption. It is marketed as demand sensing. The company has 19 customers. The invention was pattern recognition to sense short-term demand and replace traditional logic, but the innovation to drive business results is slower. Teams struggle with traditional definitions of forecasting (concepts like one-number forecasting, collaborative forecasting, and tightly integrated demand planning into ERP), and have been slow to adopt demand sensing. Market confusion also reigns with many vendors adopting the term ‘demand sensing’. The market confusion slows adoption. While other companies attempted to introduce demand sensing applications, the Terra Technology application is the clear winner to drive business results.

In 2013, Enterra Solutions introduced the use of advanced math coupled with artificial intelligence to drive learning engines using rules-based ontologies and cognitive computing. The invention is a supply chain planning learning system. The innovation is happening at visionary companies. However, in the adoption of cognitive computing, companies struggle with conventional thinking. Our minds are hard-wired to think about statistics and optimization. Learning that statistics may not be sufficient is difficult for many. For example, we have hardwired simple rules of “single ifs to simple then” logic statements because of technology limitations. We have tried to make the business work based on fixed rules in solutions like ATP, supply chain visibility, and demand insights that constrains the outcome. The Enterra solution couples a rules-based ontology to a learning engine and advanced math to enable continuous systems learning adaptation of rules. The ontology learns process relationships and then drives better outcomes.

It is clear: both of these techniques are improvements to the 1990’s definitions of Advanced Planning. They should be used together by early adopters. Invention should spark innovation, but our fixed paradigms limit our ability to see ‘what could be’. Progress is too slow. What to do? I think that we should embrace these new technologies as disruption.

Why Drive Disruption?

In food and beverage companies, I think that we are at a supply chain crisis. Consumers do not trust big-brand supply chains to deliver healthy food. They are walking with their feet to fresh and prepared foods. Demand is plummeting and becoming more complex. Buying patterns are changing quickly, and the insights are multidimensional. So, do food and beverage companies have the time to allow an invention to spark to become a gradual innovation (e.g., like the electric motor)? Or should they embrace these technologies as disruption and stabilize their investments in traditional and more legacy approaches? My answer is disruption.

In 2008, I was asked to visit DuPont to talk about demand sensing. In the height of the recession, the corporation was struggling to read market demand. Their major supply chains of automotive and housing took a rapid downturn and it took the company too long (six to eight months) to read market demand. Why so long? Syndicated data sources have a three to four week latency with the market, and the time for an organization to model syndicated data to understand market trends will take another four to six weeks. When the results are analyzed, good news travels fast in companies, but bad news travels slowly. What tends to happen in a market downturn is disbelief. Marketing and sales design incentives to close gaps, and the organization starts sledding. What does this mean? Here is the scenario. The company misses the first quarter goals. The difference is applied to the second quarter. Promises are made by sales and marketing to execute new demand-shaping programs—price, promotions, distribution incentives—to drive demand. It takes twelve to fourteen months to read the market; and by this time, the third quarter is missed. The gap is then applied to the fourth quarter. Inventory piles up, and revenues gaps are closed by pushing product into the market. This can only happen for a short period before plants are closed, layoffs occur, and major businesses are gutted. This was the case for DuPont in 2008.

This week I saw a presentation of the new project, “One DuPont” which is built upon the use of SAP SCM 7 and tight coupling of traditional APS concepts to DuPont’s budget. When I asked the DuPont presenter why they were not adopting more advanced concepts of demand sensing, the answer was IT standardization. I shook my head. The concepts of demand sensing, demand translation, and demand insights are absent in the DuPont vision. There is also a lack of recognition that the budget used in forecasting is not market demand. As a result, I expect to visit DuPont in the next market downturn. Let’s just hope that they can remain viable that long.

So, what would I do? In an SAP shop, I would stabilize the investments in SAP APO or SAP SCM 7. I would use SAP APO only as a system of record. I would redefine demand processes as more than forecasting. I would purchase a robust demand forecasting tool—JDA, Logility, SAS, or Terra Technology—and compliment it with new approaches to sense and translate demand. The new forecasting tool would write to the SAP system of record. I would abandon the use of the SAP APO DP optimizer(s).

My focus would then be on demand sensing. To accomplish this goal, I would use sentiment analysis (the reading of unstructured customer data—social data, rating-and-review information, blogs and warranty data) and mine insights weekly (tools like SAS text miner and Clarabridge) and share them in cross-functional reviews of S&OP execution (break the organization free of marketing and sales bias). The goal: bad news needs to travel at the same speed as good news.

I would also abandon the traditional concepts of one-number forecasting, tight coupling of the demand signal to the budget, and collaborative demand planning. Instead, I would focus the demand planning processes to be market-driven and outside-in. To accomplish this I would connect the sentiment insights, and couple them with weather data, market insight data (price, basket and competitive data), along with syndicated data/focus group data into a rules-based ontology to drive market insights that can be fed into forecasting and demand sensing technologies. Why? The processes of marketing and sales are too slow and have too much bias for this fast-moving world. Product lines and markets today are just too complex.

Lastly, I would implement a demand sensing technology—either ToolsGroup or Terra Technology—to replace rules-based consumption of the forecast to improve replenishment. Forecasting was designed as a tactical planning process not to guide replenishment. I would aggressively implement a demand sensing product, and where possible base it on the use of channel data to remove demand latency.

These are my thoughts. I look forward to hearing from you. I think that planning—especially the processes of demand—require a disruption. When markets shift, time is our enemy.

____________________

Life is busy at Supply Chain Insights. We are working on the completion of our new game—SCI Impact!—for the public training in Philadelphia in August and the content for the Supply Chain Insights Global Summit in September. Our goal is to help supply chain visionaries, around the world, break the mold and drive higher levels of improvement. The conference will feature case studies on demand sensing, rules-based ontologies, and the use of sentiment analysis.

Life is busy at Supply Chain Insights. We are working on the completion of our new game—SCI Impact!—for the public training in Philadelphia in August and the content for the Supply Chain Insights Global Summit in September. Our goal is to help supply chain visionaries, around the world, break the mold and drive higher levels of improvement. The conference will feature case studies on demand sensing, rules-based ontologies, and the use of sentiment analysis.

About the Author:

Lora Cecere is the Founder of Supply Chain Insights. She is trying to redefine the industry analyst model to make it friendlier and more useful for supply chain leaders. Lora has written the books Supply Chain Metrics That Matter and Bricks Matter, and is currently working on her third book, Leadership Matters. She also actively blogs on her Supply Chain Insights website, at the Supply Chain Shaman blog, and for Forbes. When not writing or running her company, Lora is training for a triathlon, taking classes for her DBA degree in research, knitting and quilting for her new granddaughter, and doing tendu (s) and Dégagé (s) to dome her feet for pointe work at the ballet barre. Lora thinks that we are never too old to learn or to push the organization harder to drive excellence.

Lora Cecere is the Founder of Supply Chain Insights. She is trying to redefine the industry analyst model to make it friendlier and more useful for supply chain leaders. Lora has written the books Supply Chain Metrics That Matter and Bricks Matter, and is currently working on her third book, Leadership Matters. She also actively blogs on her Supply Chain Insights website, at the Supply Chain Shaman blog, and for Forbes. When not writing or running her company, Lora is training for a triathlon, taking classes for her DBA degree in research, knitting and quilting for her new granddaughter, and doing tendu (s) and Dégagé (s) to dome her feet for pointe work at the ballet barre. Lora thinks that we are never too old to learn or to push the organization harder to drive excellence.

The Deserted Mall is an Important Symbol for Supply Chain Leaders

Thinking about the pervasive shifts in the technology landscape.