Last week, I published an article on outside-in planning. The article introduced the concept of self-service planning and challenged companies to rethink the concepts to adopt outside-in supply chain planning. While technologists advocate a practice of crawl, walk, run, for me, I think companies should just jump. It is a step-change, not an evolution.

For me, the concepts of outside-in and self-service planning are intertwined. Let’s start with definitions:

Self-service Planning: Decision support technologies designed for business leaders to use analytic techniques on a collaborative platform to improve business planning.

Supply Chain Insights Training, 2024

Outside-in Planning: Modeling based on channel and supply network signals. The translation of market signals from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier with bi-directional flows.

Today’s solutions are inside-out and focused on having the planner serve up answers for business leaders. The deployed technologies are challenging to use. As a result, while over 90% of manufacturing companies larger than 5B in annual revenue have an Advanced Planning Solution (APS), they primarily use Excel spreadsheets for supply chain modeling. Consequently, the current APS deployments mainly serve as a system of record, not insight.

The data and math within planning serve and stay in planning groups. Despite the advancements in business analytics, no APS solution allows for easy analysis of the plan’s fit, measuring feasibility and business outcomes. Introducing Forecast Value Added (FVA)1 analysis in demand planning is a good start, but there is more to do. As a result, companies struggle to know if they have a feasible or a good plan.

The Opportunity

Based on my research, I believe there is an opportunity to reduce the number of planning roles by 80-85%. In my past blog, I likened the journey to eliminating the secretarial pool in the office in the 1980s. Currently, supply chain planners are the least satisfied employees in the supply chain. Sadly, most planners spend six to seven hours a day in meetings and struggle to get timely information. The second disturbing fact is that business leaders cannot access planning data, so a planner must interpret the data.

As companies struggled to respond to increasing business complexity—a growing number of products, channels, and markets with regional preferences—few software applications were equal to managing channel complexity. As a result, companies hired more planners, creating a rise in planning salaries and a shortage in the market. Guess what? Adding more planners is not the answer.

By now, you are probably shaking your head in violent agreement. Yes, there is a great opportunity, but the question is how to jump. How to get started?

The Need for Intervention

Let’s start with a discussion of what will not work.

- Re-platforming Current Planning Solutions. Multiple technologists have briefed me for the last few months, eager to share their new platform. The build varies from native Cloud, HANA, or Salesforce, but the pitches are similar. The focus is on the platform; in each presentation, the company struggles to answer the question, “What problem do you solve? And, why should a business leader care?” The answer to my questions is usually met with silence. Their messaging is generally to an IT audience, assuming that the current definition of the solution footprint (taxonomy) is sufficient.

- Faster and Better Engines. This week, I was at Informs Analytics Conference. At the event, presentation after presentation focused on improving engines. The focus was driving efficiency improvements (reducing costs and improving customer service.) The issue? The discussion should start with a redefinition of the model. This is how we should jump.

I love new forms of analytics, but I think we need to rethink the models and the overall approach to maximize value. Let’s continue with a discussion of why a change is necessary. Let’s focus on why this cannot be an evolution.

The Evolution of Self-Service Planning

One of the fundamental fallacies of today’s planning solutions is that planners, and only planners, can access data. As a result, business leaders and planners are forced to do an iterative dance of modeling. The dance goes like this. Business leaders have a request. Planners answer. Business leaders have further questions, and planners respond. The process is laborious and iterative, adding to process latency (the time to make a decision).

In addition, it is hard to hire planners. Staffing is a continual fight. Good planners are scarce and expensive. Often, the planning group has high employee turnover and low job satisfaction. With the evolution of eCommerce, shifts in regional preferences, complexities of product portfolios, decline in forecastability, and increase in demand and supply variability, supply chain planning is more challenging.

Technology providers focus on serving the planner, but I find that they are blind to the larger requirements of how to serve the organization better. Today, no planning solution quickly answers the crucial questions for the business leader:

- Do I have a good plan?

- How do I improve the plan?

- What are the risks and opportunities with the plan?

- How did my organization perform against the plan?

- What was the gap? What is the value of the gap?

- How did the plan’s assumptions compare to today’s reality? (For example, inflationary costs, lead time variability, conversion rates, etc.)

So my questions are simple. Can we redesign supply chain planning to serve the business leader better, and, in the process, better serve the organization? Can we build collaborative platforms for role-based discussions across commercial (sales and marketing) and operations (manufacturing, logistics, and purchasing) teams?

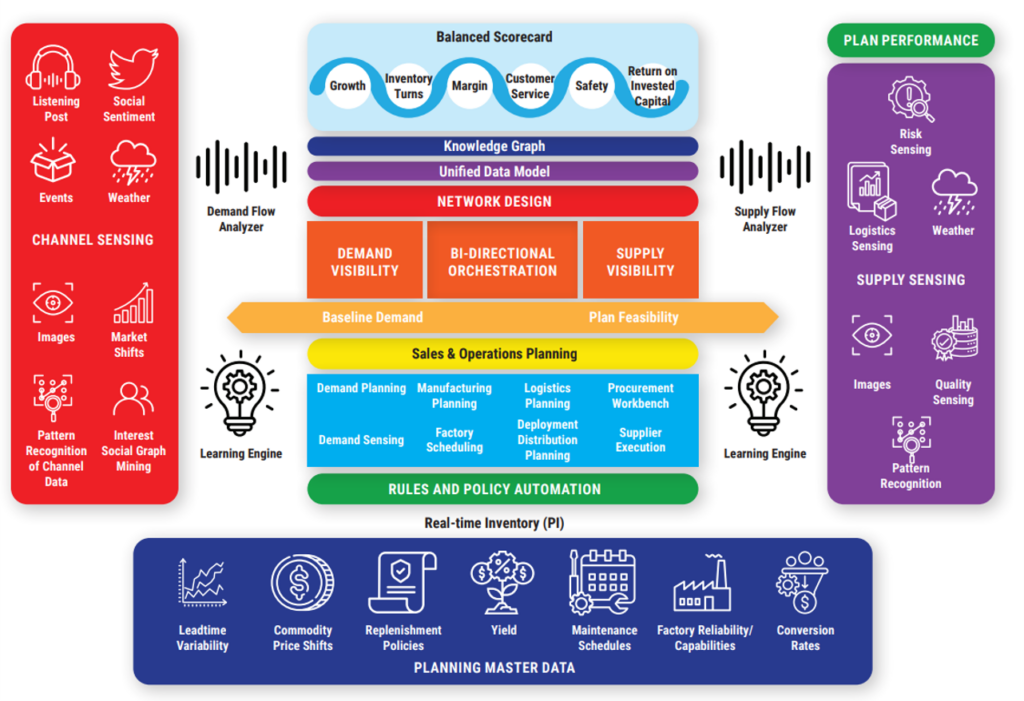

Figure 1 shows a potential representation of outside-in, self-service planning. The concept is to design the areas in orange for business leader collaboration. The goal is to maximize value through a balanced scorecard. Through work with Georgia Tech, the supply chain team can affect 70% of market capitalization in the food, chemical, and pharmaceutical industries.

The balanced scorecard aims to improve value by driving operating margin, inventory turns, and revenue/employee results simultaneously. The goal is to move the supply chain away from a functional cost-based agenda and improve value (improving margin, inventory, and revenue/employee simultaneously).

Figure 1. Evolution of Self-service Planning

The Value of Outside-in Models

Critical to this shift is the building of outside-in models. Current models are inside out.

Last week, I finished teaching a class on building outside-in planning processes. I now have taught the class to over two hundred students, and in August, I will publish a report analyzing the current state of the market providers to deliver on the promise of an outside-in model.

The premise is simple: 80% of the data surrounding the supply chain is not used. The opportunity is to make better decisions while reducing the time to make a decision (latency)—time to sense and respond to market shifts. The current latency for supply chain planning—from the time of a market event to a decision today—is 4-6 months. As a result, the company’s supply chain response is usually late and out of step with the market. As variability increases, organizational frustration grows. Most organizations are supply-centric in their thinking with a focus on supply cycles. Managing demand cycles is a new concept.

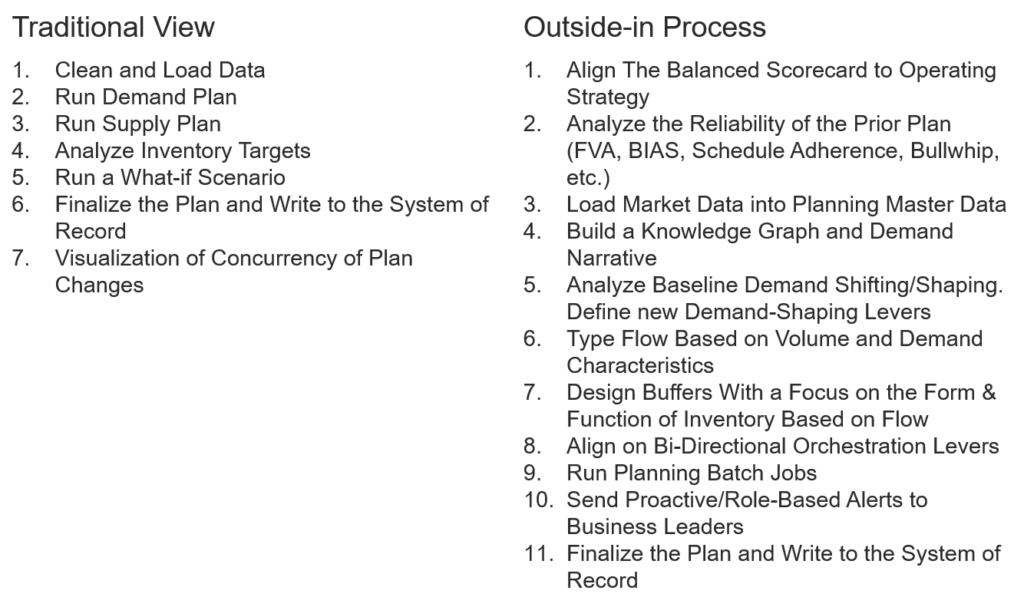

In an outside-in model, market data is used to classify demand flows. The demand flow characteristics are then matched with supply tactics. Companies do not have one flow; they typically have five to six. As shown in Figure 2, the demand streams are classified and reclassified with each run of the planning engines. This process of reclassification is a valuable input for proactive alerting.

Figure 2. Mapping Demand Streams

The next step is to align supply strategies with demand streams. Most companies have five-to-seven distinct demand streams requiring the use of different supply strategies:

| Stream | Forecastable | Goal | Outcome | |

| 1. Turn Volume | Make to stock | Very Forecastable. Focus on Improving Forecast Value Added (FVA) | Replenishment | Efficient: Produce at the Lowest cost per unit |

| 2. Short Cycles | Sense Demand and Produce Based on a Flexible Design with Short Cycles | Seldom Forecastable. Improve Sensing to Reduce Demand Latency. | Flexibility to sense and respond | Responsive |

| 3. Seasonal | Inventory Build or Asset Capacity to Ramp for a Seasonal Demand | Usually. Plan for patterns of demand. Ramp for a seasonal response. | Maximize market Opportunity. | Agile |

| 4. Product Launch | The Launch of a New Product | Seldom. Sense shifts in decoupling points. Reduce demand latency. | Growth | Agile |

| 5. Intermittent | .Make to Order and Configure to Order. | Somewhat. Requires advanced modeling techniques. | Maximize Customer Service | Agile |

| 6. Long Tail | Configure to Order or Make to Order | Not forecastable. | Maximize Customer Service While Minimizing Waste | Agile |

| 7. MRO | Additive Manufacturing | Not Forecastable Machine sensing to improve proactivity. | Maximize up time | Agile |

Getting Started

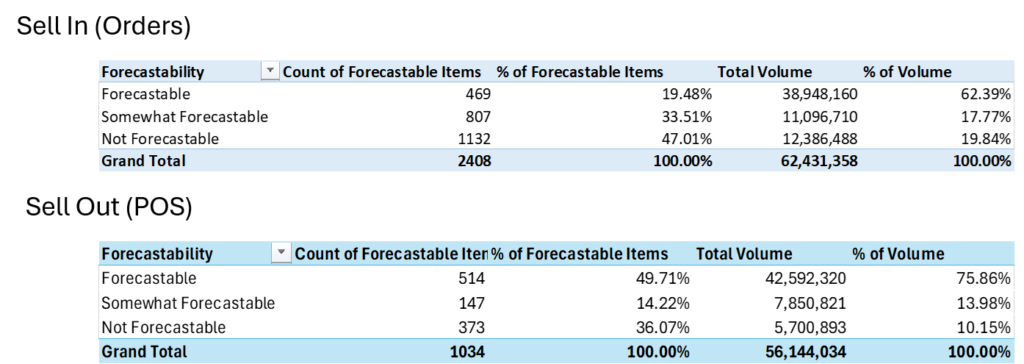

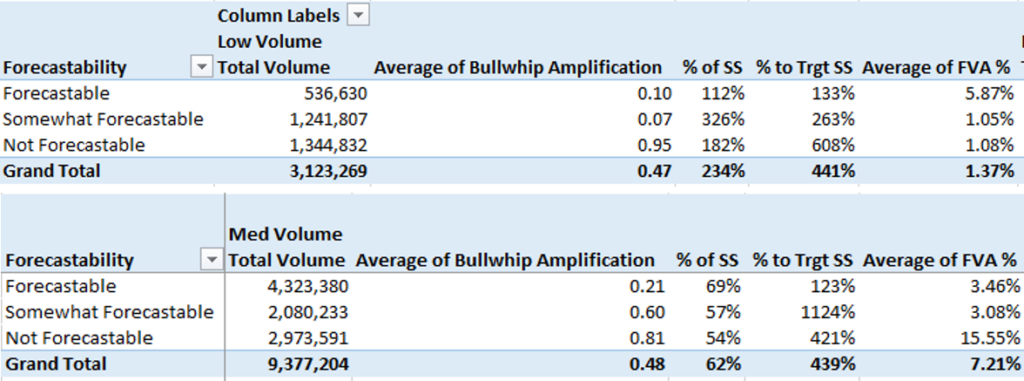

To understand the progression of thought, let me walk you through the final homework analysis of a student from my recent class on outside-in processes. Let’s call him Liam. He works in consumer durables. His team has multiple APS solutions. He feels none work well.

In the class, I ask the participants to analyze forecastability and volume patterns to understand demand streams. Unlike conventional thinking, where all demand is optimized together as one output, in the outside-in process evolution, we first type the demand streams and then align supply strategies to drive/improve outcomes by streams. This analysis occurs with each run of tactical planning.

The homework helps Liam to understand forecastability, distortion, and latency. Note in Liam’s example that only 20% of the turn items are forecastable through conventional means. The distortion of history post-pandemic makes this exceptionally problematic for most companies. His bullwhip factor is .45. (The order signal has amplification and distortion.) The order latency is five weeks. (Demand latency is the time to translate the purchase in the channel to an order.)

Figure 3. Analyzing Demand Streams

Using the Forecast Value Added (FVA) Analysis, the improvement potential is a 6% improvement in FVA worth 5.6M in inventory value. Liam’s conventional forecasting process uses a ship-from model based on orders, with an FVA improvement of 1.29%. In comparison, the improvement for a sell-in forecasting model using channel data was 7.36%.

Figure 4. Comparison of FVA for An Inside-out Demand Model Using Orders Compared to an Outside-in Model Using Channel Data

In my last blog, I state the need to jump. You might ask, “How can we jump if there are no potential pre-packaged solutions or system integrators to do the work? “

For perspective, we are about a year away from potential market introductions of self-service outside-in planning processes.

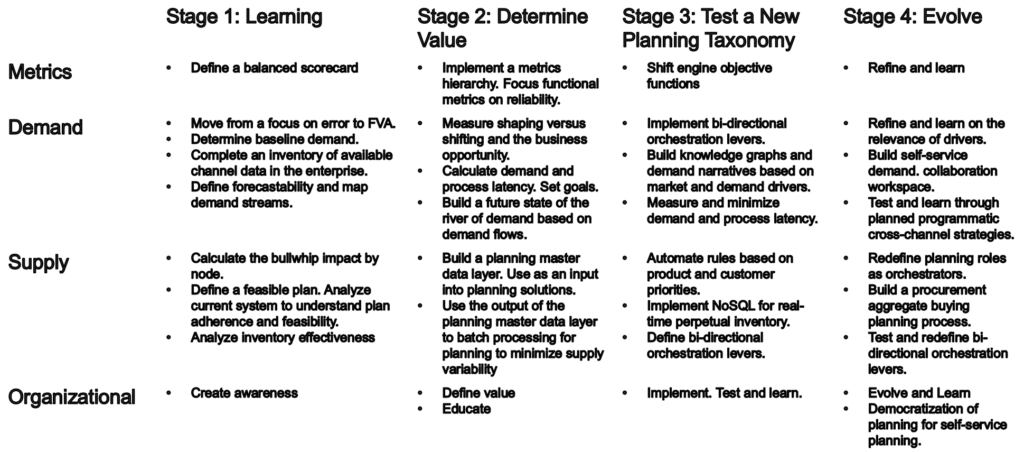

Meanwhile, I recommend focusing on the first column of the maturity model. Define a balanced scorecard, learn how to speak the language of demand, explore the concepts of bi-directional orchestration, and socialize the value. (Use Liam’s analysis as a guide.)

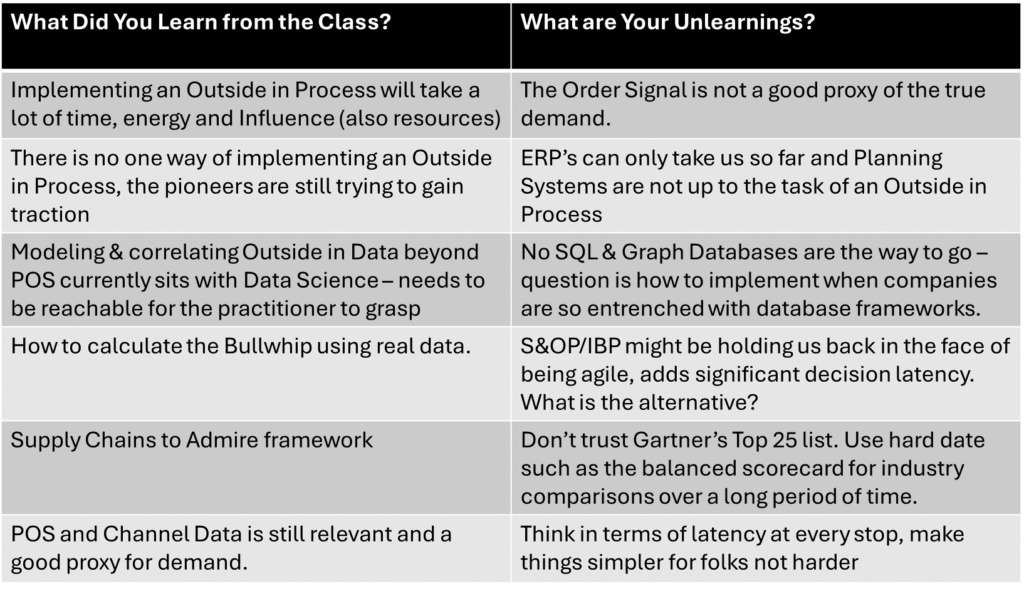

In the class, I ask the participants to list what they learned and contrast them with the “unlearnings.” The unlearnings are beliefs that underlie their current paradigms that must be thrown away. In Table 1, we share Liam’s learning and unlearnings.

For perspective, here is the maturity model for building outside-in processes.

Figure 5: Maturity Model for Building Outside-in Self-Service Planning

In summary, building an outside-in planning process is far from the crawl, walk, run approach. Instead, it is a step change made possible by new forms of analytics. Self-service and outside-in planning are tightly intertwined opportunities as we move forward, offering a great opportunity.

I hope this helps! For me, it is 5:00 AM EST. It’s time to get some sleep before my flight tomorrow. I look forward to seeing your comments.