This morning, the New York Times pushed me an article by Peter S. Goodman titled “The Supply Chain, Reconfigured.” His narrative centers on the evolution of the global supply chain, focusing on labor arbitration and ignoring geographic distance and shipping issues. He believes that the internet, container shipping, and global banking shrunk the supply chain. He recently wrote a book titled “How the World Ran Out of Everything.”

A populist narrative centers on global outsourcing and rising risk issues from war, climate change, and global unrest. These are undoubtedly issues. However, my worldview is that the larger shifts are far more systemic, requiring a call for action that is going largely unheard.

I would like us to move past the conventional view of sourcing strategies and globalization to drive improvements to the supply chain in a variable world. The populist narrative of sourcing globalization is only part of the story. Let me explain.

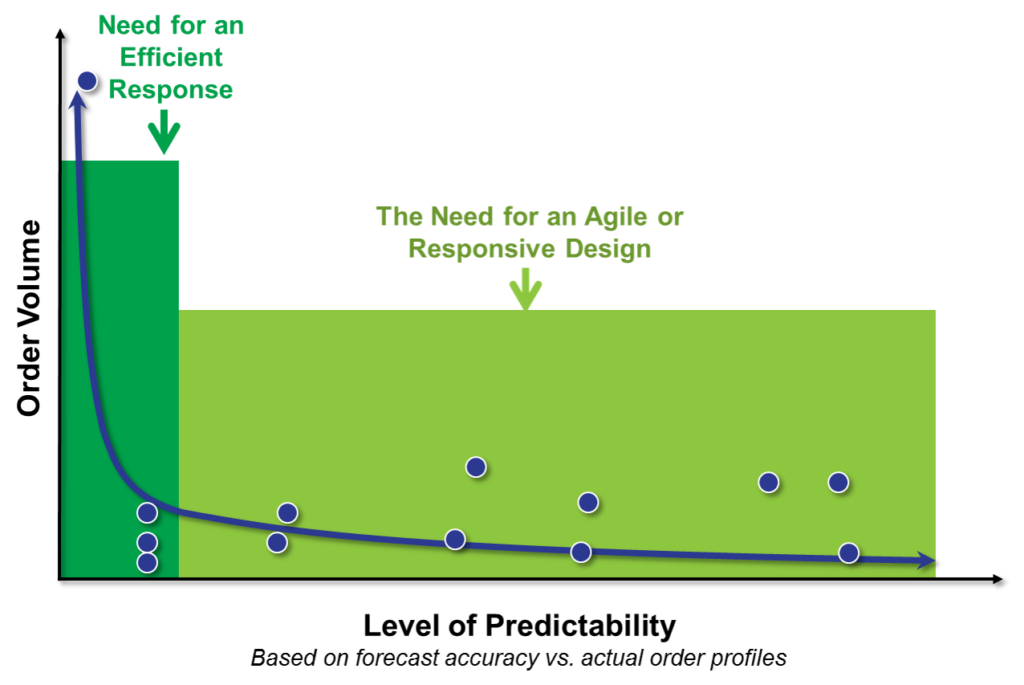

Forecastability. Traditional supply chain practices are no longer best practices. This is especially true in the world of demand management. Today, due to the increase in the long tail of the supply chain and changing customer dynamics, less than 50% of items are forecastable at an item level. (Data sourced from the students in my last two classes of outside-in planning where the COV is greater than .70.)

In Figure 1, we depict the long tail. The only products that can be efficiently outsourced with long lead times are in the “forecastable” column. Today, this is 20-22% of volume. In 2015, the forecastable volumes were over 50%. Not so today.

How did this happen? Unabated growth in product complexity and uncontrolled demand shaping programs. We match demand and supply volumes in Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) but do not align demand and supply cycles. The average company has five to seven supply chains that require alignment.

Figure 1. The Evolution of the Supply Chain Long Tail

I am interviewing 40-50 recent Advanced Planning (APS) implementations to understand success and build a maturity model. So far, I have interviewed twenty companies. They are all modeling items at a location level without measuring forecastability or Forecast Value Added (FVA). The predominant error measurement is WMAPE, often at a 30-or 60-day lag.

In 8 out of 10 companies I work with, this approach creates a negative FVA introducing error and waste into the supply chain. Yet, companies feel good because the historical practice was to measure error. We speak of waste reduction and sustainability through a supply-centric lens. Too few are questioning the products that should have never been manufactured. Let’s face it: our historical practices for demand planning create waste in a more variable world. Companies continue to drive these practices following historic practices without questioning if they are the best practices for today.

Improving the forecast reduces waste, helps growth agendas, and improves margin. The sad thing is that it is not that hard. The tragic narrative is that few companies have made the necessary changes to manage unforecastable items.

An unforecastable item requires a different technique. It might be a change in modeling technique (like an attribute-based model), shifting the bottoms-up and tops-down forecasting approach (forecasting at a different place in the hierarchy), or the use of channel data. Sadly, most companies will never know because they are blindly measuring the wrong metric and driving a supply-centric agenda.

So, my reply to Peter S. Goodman is, “Should the item ever be sourced or scheduled for production?” Too often, I see this as the root issue in this world of higher volatility.

The Functional Manager: Supply-centric or Manufacturing Thinking. The second issue is that process companies are manufacturing-centric, while discrete organizations are supply-centric (procurement). (A process-based company is a make-to-stock process, while a discrete company operates a make-to-order or configure-to-order process.) The traditional management of functions without aligning make, source, and deliver together creates waste.

There is a need to improve the management (buffers and constraints) of supply cycles (make, source, and deliver) based on actual lead times and lead time variation. This requires building a planning master data layer system and designing network strategies to improve and align cycles to outcomes. This is impossible in 80% of the current Advanced Planning System (APS) approaches.

The functional manager’s days of focusing on OEE (Operational Equipment Efficiency) and POV (Purchase Price Variance) need to end. Functional metrics throw the supply chain out of balance, creating waste and increasing turbulence. They also result in manufacturing products that may not be needed.

The issue? Over the last two decades, companies raced to take advantage of lower labor costs without considering the total costs of making, sourcing, and delivering together. Or the management of cycles. Order cycles compressed with the evolution of multi-channel strategies. The shortening of order cycles and the lengthening of supply cycles was incongruous. The gap was acerbated by the increase in supply variability. Today, only 9% of companies actively design their supply chains. Financial teams made most of these global sourcing decisions on Excel spreadsheets.

So, my reply to Peter S. Goodman is, “Not so fast. Are traditional practices at play here?”

Global Markets Required Global Sourcing. In most populist narratives on sourcing, many fail to realize that regional markets are essential to fuel growth strategies. Sourcing in China for the Chinese market is essential. The shift from regional to multi-national supply chains required redesigning decision-making processes. Companies needed to evaluate the role of the division, the region, and the corporate teams to minimize bias and waste while improving profitability and growth. Few accomplished this well.

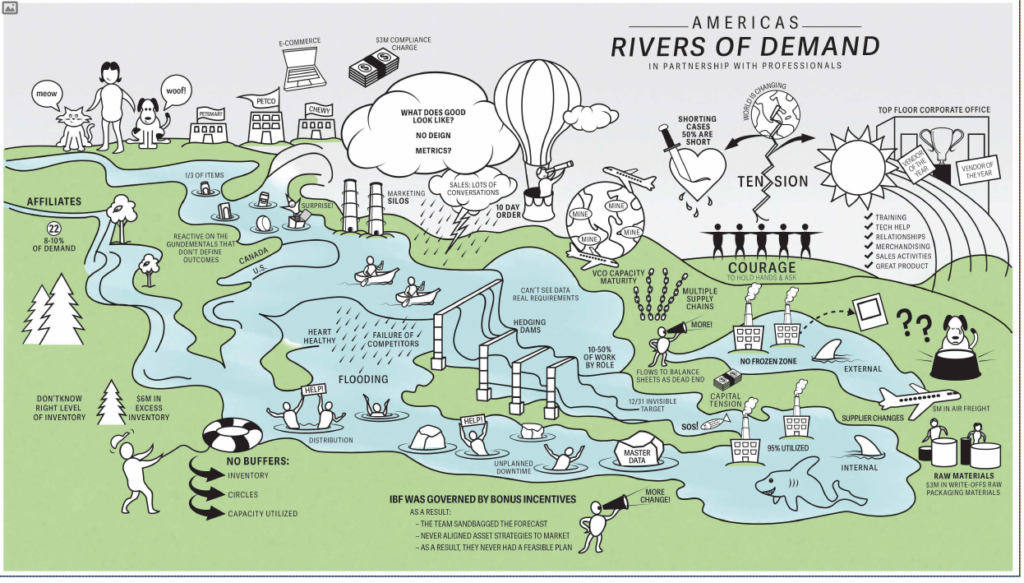

Consider the image in Figure 2 of a pet food manufacturer. The company operated an Integrated Business Process (IBP or S&OP) designed by a large strategic consulting firm that focused on demand and supply balancing at a regional level. The local team “sandbagged” the forecast with a severe negative bias to make annual bonus incentives, but as a result, it was never able to build the “case” to invest in assets to be successful in manufacturing to instantaneous demand.

In addition, inter-plant shipments labeled here as “affiliate volume”, were never managed. These orders just showed up and took priority despite the severe lack of capacity to meet the regional volumes. The affiliate orders lacked a disciplined approach. The role of the regional supply chain and the relationship within the global supply chain was never defined.

Figure 2. Depiction of a Global Company with Regional Governance without a Global Supply Chain Strategy

So, my reply to Peter S. Goodman is, “We expanded global sourcing without consideration of how to best manage global decision-making. What was the impact on waste, expediting, and missed customer shipments? Isn’t this the real story?”

Wrap-up

In short, the populist narrative on supply chains is too simple. My reply? Peter S. Goodman, “I only wish that the supply chain was reconfigured.” Or re-imagined, like Van Gogh’s Starry Night in the image.

Without questioning traditional supply chain practices, I think we are just moving the puck without scoring, to use an ice hockey analogy. Often, the puck is moving backward, helping us to lose ground.

The evolution of the global supply chain (movement of products and materials from one country to another to satisfy demand) was based on three assumptions: rational government policy, low demand and supply variability, and availability of materials and transportation. Our technologies and processes have not adapted to the fact that none of these assumptions are true today.

The increase in demand and supply variability and the need to effectively compete in a global multi-channel world requires more than just a discussion of sourcing strategies.