During the 1980s, I was part of a management team for a large manufacturer. My job was redesigning work to improve effectiveness. The plant was 24 acres under one roof. The concept was a factory with many factories in a common facility. The Company was attempting to gain economies of scale by grouping manufacturing technologies within a common infrastructure to reap the benefits of a co-generation facility, a centralized warehouse, and a talented administrative team. This experience was a great growth opportunity.

Each morning, an administrative assistant met with a cup of coffee. She also gave me a white typed index card with my schedule for the day. The calendars were tightly controlled by a secretarial pool of 10-15 employees. (The index card was designed to fit into a man’s shirt pocket. As the only woman on the team, I always laughed that I had no place to put it, but I did not buck the system. I would carry the card loosely tucked into my pad of paper all day. Many times, I would lose it and the secretaries would laugh.)

Early in the 1980s, the company invested in an IBM/360 mainframe along with three “portable computers.” We were excited! These portable computers were anything but portable. Engineers could sign up for hour-long blocks to use the new systems.

Supply Chain Planners Analogous to Secretarial Pools?

By the late 1980s, personal computers were starting to permeate the office environment. While the secretarial pool argued about the merits of Word and Word Perfect, I sorted through their request for the latest typewriter with software memory. In parallel, I started working on a project to eliminate the secretarial pool. It was clear to me that this self-serving group buffered communication and made the office more political.

Initially, the concepts were blasphemy. At the time, business leaders did not know how to type and had no idea how to use a computer. Training ensued, and the expectation of changing work was shared. Within a year, we eliminated the typing pool. Surprisingly to most, the work became more efficient and less political.

Why am I telling you this story? I feel that the work of planners is analogous to my typing pool experience. In my forty years of studying supply chain planning, the planning groups became larger, but with questionable results. I have clients that less than 100 planners in the 1990s, 500-1000 planners in the period of 2000-2020, and now have over 1500 planners. The answer is not more planners.

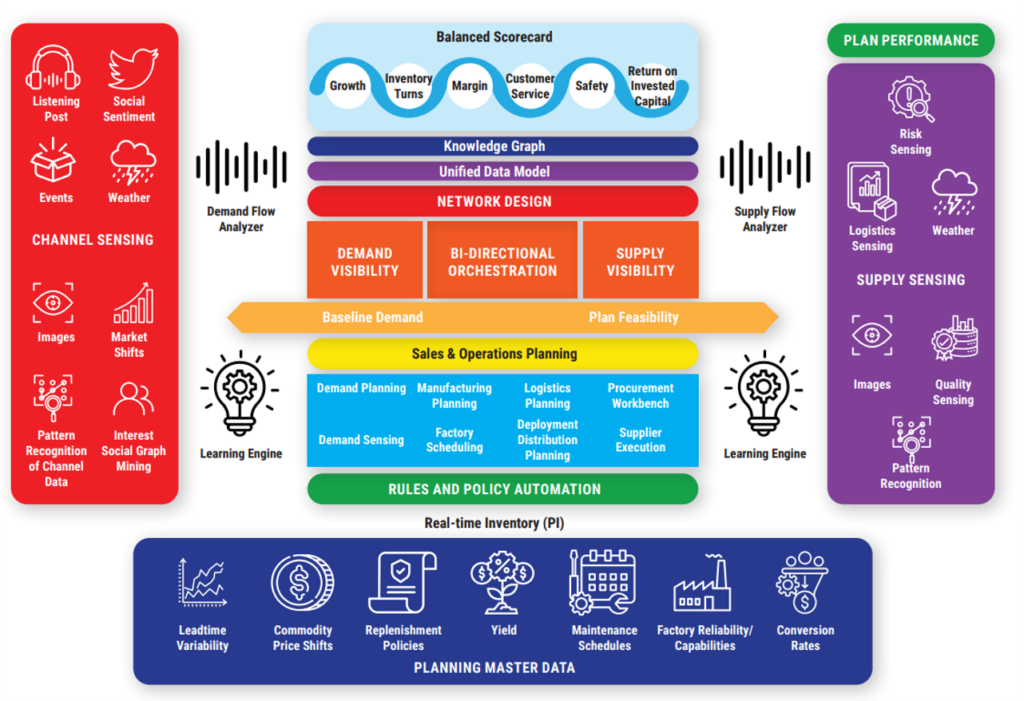

If I had a magic wand, I would redesign work to transform the planning role to become data orchestrators with supply chain planning becoming self-service by business leaders. I depict this functionality in orange in the model in Figure 1. (For more on my work on outside-in planning processes, check out my report .)

Figure 1. Taxonomy of Outside-in Planning Based on the Art of the Possible

To accomplish this goal, we need to discard the current crawl, walk, and run models and just jump. I would never have eliminated the secretarial pool by asking them their opinion.

The journey starts by redefining work using the new capabilities defined by the Art of the Possible. (When I speak of the Art of the Possible, I am reflecting on my learning about the power of the Graph database, NoSQL, no-code techniques, Generative AI, R, Python, machine learning, unstructured text mining, etc.) We sidestep vacuous terms like digital supply chain and attempt to measure and redefine flows based the redefinition of planning. (Digital signals are very black and white while planning is very gray.) In the new architectures, the Orange layer above the traditional deployments (shown in blue) become the collaborative data sharing area for business leaders.

Why Jump Now?

The answer lies in business outcomes.

Twice a year, I teach an open class for business and technology leaders to explore the Art of the Possible while redefining planning processes to be outside in. At the start of the class, we discuss why the order is a poor proxy for demand. In my first classes, I taught the group how to speak the language of demand—forecastability, Forecast Value Added (FVA), backcasting, demand and market latency, and market drivers. In the process, the students learn that only 20-25% of the flow of the supply chain can be effectively managed as an efficient supply chain (lowest cost) and that more and more items are not forecastable at an item/location level. (The average was 45% in my recent class.) We explore the concept of holistic inventory strategies focused on the form and function of inventory. In the process, we learn that only 15-20% of inventories are safety stock and that the current APS frameworks do not enable a holistic analysis of the form and function of inventory. The class also discovers the current blackholes of the supply chain (direct procurement and contract manufacturing. The students learn that there is no definition of end-to-end planning because the current taxonomies for modeling are fragmented. (Revenue management is siloed and distinct from demand management, while Transportation Management (TMS) has nothing in common with Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP). The tight integration of APS to ERP introduces nervousness in complex systems.)

The answer is not as simple as connecting Customer Relationship Management (CRM) to Advanced Planning (APS). Or gradually introduce outside-in signals to conventional demand planning. The shift from Inside-out to Outside-in is impossible using a crawl, walk, and run strategy. Instead, we need to Jump.

The So What?

Based on three years of testing, we find that the redefinition of supply chain planning to be an outside-in market-driven process improves Forecast Value Added (FVA) by 10%, removes bias, improves the time to know by 150%, and decreases the bullwhip by at least 50%. In the research, we find that deploying an outside-in model always beats an inside-out model, reducing process and data latency while improving the organization’s ability to make decisions at the speed of business.

When supply chain planning models evolved in the 1980s, the work processes were defined for small teams, not the hundreds or thousands of planners that organizations have today. Today’s organizations are more complex. The untethered business complexity cannot be solved by throwing bodies at planning.

| Organizational Impacts | Process Impacts |

| The alignment gap between sales and operations groups grew threefold in the last decade. | 85% of inventory decisions are not managed in Advanced Planning Solutions. Only 15% of inventories are safety stock. |

| Focus on efficient supply chains (lowest cost models). | 40-50% of items are not forecastable at an item/location level. |

| The supply chain became a function within a functional organization focused on supply. | In 8 out of 10 organizations, the current processes and technologies degrade the forecast reducing Forecast Value Added (FVA). |

| Lack of recognition of supply chain flows and multiple supply chains. | The evolution of S&OP to IBP increased process latency in 70% of companies. |

| Growth of the bullwhip effect by 2-3X, resulting in the overbuying materials and over-production of finished goods. |

The problem is more profound. There is a shortage of planners in the market, and the aggregate knowledge of planners today has declined. As boomers retire and planners change jobs, we are not retaining the basics on supply chain planning. For example, in my qualitative research studies, I find few can answer the questions of what defines a feasible plan, how to measure inventory effectiveness, or how to tune and refine models. The shifts over the last decade are profound:

Is the Answer a Supply Chain Center of Excellence?

I think that the answer is no. Let me explain.

Supply chains are complicated and vital to a firm. So, creating a Supply Chain Center of Excellence might sound like a good idea to start. Right? I used to think so, but now, I say, ” Be careful. One in two fail, and the failure rate is increasing.” Today, 56% of global multinational companies greater than 5B in revenue have a supply chain center of excellence. They take different forms. Some are focused on project implementation; others are attempting to improve supply chain talent by defining career paths, training, and skill development, while others serve in an audit capacity.

In my class on this week, the question on “Why do Supply Chain Centers of Excellence Fail?” The top reasons were:

- Distant and self-serving. As the organization evolves, they Lose focus on serving internal customers.

- Lack of aligned metrics. Few companies are clear on the definition of supply chain excellence.

- Lack of executive buy-in. The strategy choices are independent and not aligned.

- Value? Hard to measure the value of the COV. It is difficult to measure and hold a COV accountable.

- Scope. The COE often gets pulled into day-to-day issues and is not able to manage the longer-term issues

- Governance. Ability to make organizational changes.

- Alignment. Value may be in conflict with other teams.

- Unbiased thinking is a requirement. Clarity on mission.

- Education and leadership. Some are very technology focused.

How to Drive Success?

Clear charters and definitions matter. Like the secretarial pool, we need to redefine work, and just do it. The answer is not crawl, walk and run or build a Center of Excellence. Instead, it takes leadership. When it comes to planning, we need to take the leap of faith and improve business outcomes.