I am taking a break from my Big Data Supply Chain Series to post a few articles that have been in the works for a couple of weeks. I just wanted to put some diversity into the blog. I hope that you enjoy this post on working capital and redefining the value chain.

Software optimization improved it. Investments in global markets accelerated the need. The recession was a shock. Supply chains withstood the shock and the results are in.

What we now term the Great Recession spanned the period of 18 months from December 2007 through July 2009. It shook the core of most companies. Supply chain organizations cruising forward in neutral were suddenly jerked in hyper drive to answer questions about demand, cash flow, product portfolios and markets in a way that never happened before in our lifetimes. Supply chain discussions became boardroom debates. It elevated the importance of supply chain management basics.

The results are in. Business reporting for the 2009 business cycle is completed. In 2010, the average company grew .56%. Yes, revenue increased slightly while working capital was down 2%. In July 2011, CFO magazine reports (reference article http://careers.cfo.com/article.cfm/14586631) that Days of Working Capital (DWC) and Days of Inventory Outstanding (DIO) each improved 1.1% in 2010. These were modest gains, but the worst performance in half a decade. Should we hang our heads and be ashamed? I think not. Surprised? Read on and see if you agree.

To make my argument, I focus first on the global process leaders in chemical, household products and pharmaceutical industries. They are unquestionable industry leaders. While CFO magazine reports slight improvements in the average supply chain, in these global process industry supply chains, things were less rosy in 2010. For these leaders, the average days of DWC and DIO returned to 2004 levels. While many could argue that these companies are hoarding cash and getting lazy, I think that there is more to the story.

I then focus my argument on what I feel is the real opportunity: redefining value in the value network. To make this argument, I purposely chose a relatively simple regional supply chain–food manufacturing in the United States–where I feel that there is a clear case for change. I had several value networks that I considered that tell the same story, but due to the limitation of space, I focus only on one. The lessons are applicable for all value chains. It is now time to tell the story. Let’s take a look behind the numbers.

A Decade in Review

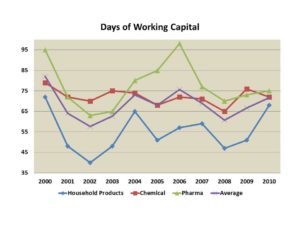

To see the real impact, let’s look a the trend. It is more telling than a few data points. After a decade of supply chain investments, the average process company has improved Days of Working Capital (DWC) by 10 days (an average of 72 days of working capital in 2010 versus 82 days of days of working capital in 2000). In the last ten years, the companies survived the recession, upped the ante on service, and made strategic investments in global sourcing (buying in aggregate globally increasing raw material working capital costs.)

Figure 1: Year-over-Year of Working Capital Results for the Global Process Leaders

The greatest improvement over these years was in the pharmaceutical industry. After reeling from the impact of globalization, and going through major mergers and acquisitions, the pharmaceutical companies have corrected—maybe even over corrected their inventories—to set their supply chain on course. As can be seen in figure 1, these three industries are now performing at a similar level.

The greatest improvement over these years was in the pharmaceutical industry. After reeling from the impact of globalization, and going through major mergers and acquisitions, the pharmaceutical companies have corrected—maybe even over corrected their inventories—to set their supply chain on course. As can be seen in figure 1, these three industries are now performing at a similar level.

The Low Hanging Fruit is Harvested

I have thought about these numbers for the last six weeks. In parallel, I am in the process of interviewing leaders for my book, and it has given me a great perspective. Based on my seven years as an industry analyst and over thirty interviews this year, I feel that the supply chain working capital results have plateaued. In my opinion, the work within the enterprise –improvement in cash-to-cash processes and optimization of inventories–is largely completed. I feel we have harvested the low hanging fruit. Technology enabled the building of global supply chains, increased span of control and accelerated visibility for decision making. For this, we should be proud. To differentiate, we now need to shift our focus.

Put the Working Capital to Work

The new opportunity lies within the crevices between organizations. It lies between companies in the value network. However, we cannot get there from here. It is a major change management opportunity. Why? Our processes are inside-out, not outside-in. Our process focus is vertical (within silos), not horizontal (across value chain). We are just beginning to build horizontal processes to drive value networks. We reward efficiency not value. This is our next frontier. We are in our infancy. But, this does not mean that you cannot take the first steps. Here I share insights on three steps that you can take with their suppliers.

Take Ownership of your Entire Supply Chain. Guilty? Have you talked about collaboration, but not walked the talk? Are you guilty of pushing costs back in your supply chain to suppliers that have a higher cost of capital than you do? For many, this is the case.

Reference figure 3 to see that food manufacturers are guilty as charged. For the last ten years, they have talked about collaboration; however, the total cost of working capital for the value chain has not gone down, it has gone up slightly and shifted backward. As an industry, they have pushed the cost of working capital and inventory back into the supply chain on to packaging suppliers that have a higher cost of capital. The end result, for the manufacturer and for the value chain, is higher costs and lower service.

Figure 3: A Closer Look at Working Capital in Food Manufacturing Value Network

Find out if you are also guilty. Use the CFO data to plot DIO, DWC and the cost of capital for you and your suppliers over the past ten years. As you do this activity, think how you could improve working capital in the TOTAL SUPPLY CHAIN. To make this better, hold a Kaizen event. Look for opportunities to improve forecast accuracy and information sharing.

Stomp out Waste. Go one step further. Map the waste-empty miles, slow moving inventories, obsolescence, rework, returns—and look for the new opportunity. Put metrics in place to encourage employees to reduce this waste. Let me give you two examples.

A well-intended food manufacturer found that there was a 9 million dollar opportunity to reduce spoilage in grocery retailer store through the deployment of new technology; however, they could not build a guiding coalition to work the opportunity because it did not directly affect anyone in the supply chain’s Profit and Loss (P&L) statement. Companies are incented to push product into the value chain, but the supply chain is not incented to own performance at the channel.

Likewise, forecast error for a food manufacturer for a new product is 90%. This error translates into waste: piles and piles of packaging material that is written off. Find out how much this is worth with your suppliers and focus on the root cause. Use advancements in attribute-based forecasting through technologies like Logility, SAS Demand-Driven Forecast Server, and Oracle/Demantra to better forecast new product launch. Use technologies to sense demand—coupling Terra Technology Demand Sensing and downstream data from vendors like Relational Solutions, Retail Solutions, Shiloh, and Vision Chain—to reduce demand latency for the packaging supplier. Today’s latency of information (from the shelf to the supplier) averages 8 weeks. This does not have to be. Implementing a new approach can cut this from weeks to days. Think about the impact on write-offs, inventory and working capital.

There is often a direct correlation between a company’s accuracy of data and information latency and waste. Let’s face it. Most of the connectivity between a manufacturer and a supplier is archaic. The supply chain still runs on the back of the fax machine and email. Challenge your employees to think about how you could improve working capital and speed of your supply chain by improving connectivity. Align metrics to focus on this opportunity.

Be Easier to Do Business With. Today, manufacturing companies are looking at the cost of the transaction. The work with suppliers is in procurement: haggling over the lowest cost of unit delivered. Less than 5% of food manufacturers are looking at the total cost. Invest in cost-to serve technology and lower your total cost by being easier to do business with. Gain insights by asking your suppliers to benchmark your cost-to-serve and implement gain sharing. (Cost-to-Serve technologies include Acorn Systems, Equazion, and Jonova.) A leader in this work is General Mills. Their presentations at the F4SS conferences are impressive. This work has reduced 1 billion in costs, but more importantly put more value into their value chain. I am proud of their work on building horizontal systems to work with suppliers.

What do you think? Have we harvested the low-hanging fruit? Is it time for us to rethink what we have learned in the last ten years in our supply chain and apply it to our value networks. I think so. Do you agree? I welcome your perspective.

Next week, I will continue my writing on Big Data Supply Chains by sharing insights on new solutions and potential case studies. Until then, if you are in North America, have a great Labor Day vacation.