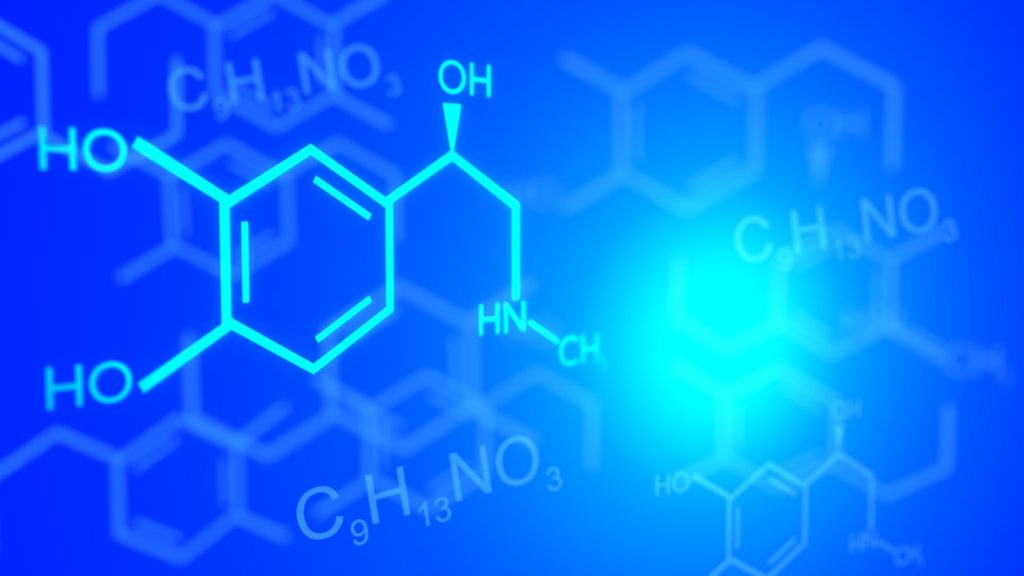

In my recent work with clients, I have been thinking a lot about S&OP and how we screwed it up. Let me take you back to some research findings that I shared last year for those who might not follow my blog. In Figure 1, note the decline in perceived S&OP effectiveness over the past three years. This data collected before the pandemic shows a sharp decline that became even worse during the COVID-19 response.

Today, many of us are on conference call after conference call in an endless loop of meetings with little time to question the effectiveness. I want to break

Figure 1. S&OP Effectiveness in 2019 Versus 2016

To understand why dissatisfaction is increasing, I have been doing some visual facilitation with a cross-set of business leaders to gain insights. The answers are not straightforward, but each participant’s response has similar storylines. Each of these steps resulted in the reduction of S&OP effectiveness.

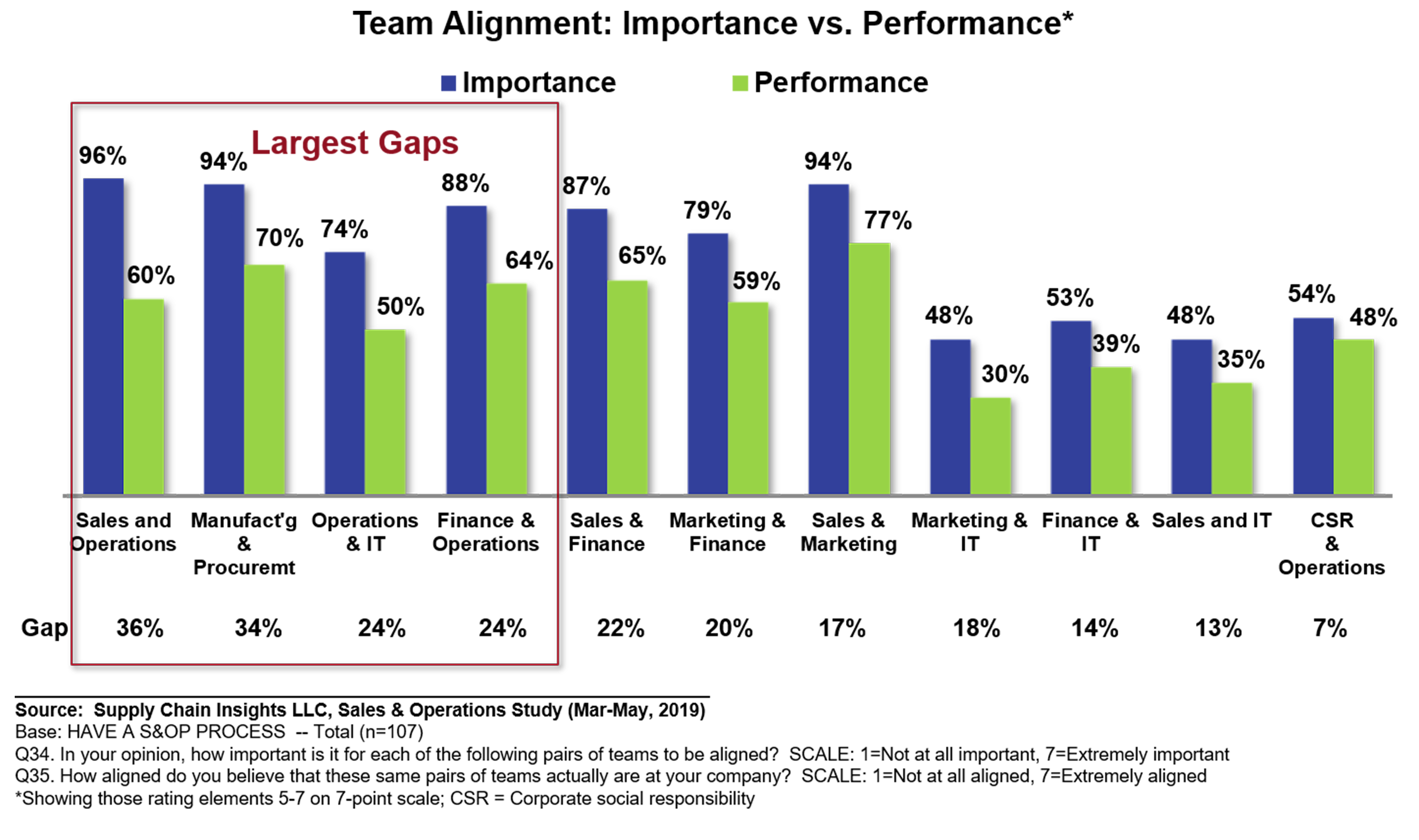

1. Tight integration to the financial budget through S&OP. This resulted in gaming by sales and marketing for bonus objectives and trade funds and systematic “beating” of the back office participants to drive costs out of the system.

The goal of an effective S&OP is to actualize opportunity and mitigate risk. Tight integration to the budget is a barrier to accomplish the goal. Instead of tight coupling, the budget should be visible as an indicator, but should never be a constraint. Instead, S&OP output is used by leaders to continually update and refine the budget.

Figure 2. Role of the Budget in S&OP

Turbulence around the S&OP process increased, insulating the organization from sensing and responding to market signals. (Market signals include consumption data, channel insights, and events.)

When I ask executives to draw their supply chains today (an activity that I love to do to understand their mental models), companies will often draw a dead pool around S&OP. One company even used the metaphor of a Ferris Wheel that goes round and round to goes nowhere. In short, a lot of organizational energy spent, but with poor outcomes. As shown in Figure 2, companies that tightly integrated S&OP into the budget did worse before the pandemic but struggled even more managing the COVID-19 response. This is even worse if the company mandated IT standardization of planning to ERP.

2. Lack of Clarity. Role of the Forecast. In 1992, I worked for a supply chain planning technology provider, and the role of the forecast was clearer. Back in those days, most supply chains were regional. The forecast provided input for manufacturing to see and manage constraints in the tactical planning horizon and procurement to align with strategic buying. Today, the role of the forecast is less clear. Many organizations attempt to tie tactical forecasting to improved replenishment (which tactical forecasting was never designed to do) and throwing the supply chain out-of-balance. How so? Many of these models attempt to model unforecastable data–the coefficient of variation is too high in many of these sales-driven models. There is confusion between the role of tactical forecasting and demand sensing. Demand sensing is a process capability in the shorter-term horizon that is more granular to drive better replenishment.

3. The Myth of One-Number Forecasting. Someone that advocates the need for a one-number forecast does not understand supply chain planning. There is a need to agree on a common plan with many numbers versus a “one-number plan.” This may seem like a nuance, but it is an important difference. The needs of sales forecasting, financial forecasting, and supply chain forecasting are very different. Each group needs customized views in a demand visibility system to help translate mix, volume, and currency in meaningful ways with baseline demand visibility. A frequent issue is the lack of discipline in planning processes and the understanding of each decision-making. In Figure 3, I share some definitions. (Interestingly, in each session I am facilitating, I ask global organizations if these can be collapsed, and mature supply chain leaders overwhelmingly answer “NO”!)

Figure 3. Planning Horizons

I have about ten more, but in the absence of time, let me leave the reader with these top three. I would love to hear from you.

Wrap-up

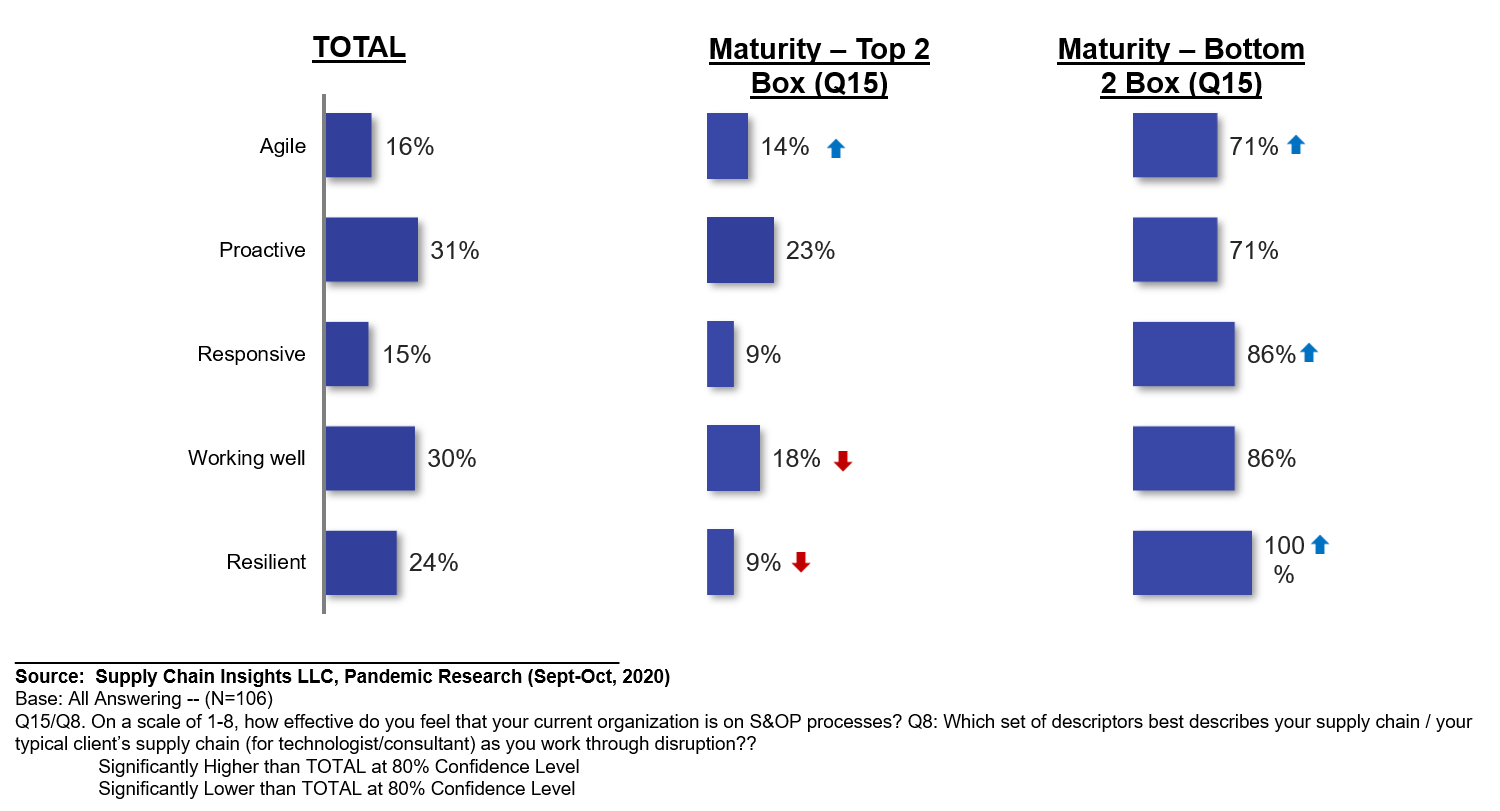

During the pandemic, companies became reactive –frequent meetings and emergency control rooms– but did not drive better outcomes. In recent research, teams rate supply chain effectiveness lower during the pandemic. (Look for this research to publish soon.)

Supply chain leaders, like firefighters, get an adrenaline rush from reactive behavior. The caution is that reactive behavior does not help the organization be more proactive. S&OP is the most valuable process to drive value. Reactive behavior undermines the effectiveness of S&OP. As we look to build better post-pandemic, S&OP is a great place to start.

See You At the Supply Chain Insights Global Summit?

We will take the risk that everyone can get COVID shots and tests and do an in-person event in September. We will also have a virtual feed for those unable to travel.

In preparation, I am handpicking the speakers and finishing up the Supply Chains to Admire analysis for 2021. If you have a story you would like to share; please drop me an email at lora.cecere@supplychaininsights.com.

Please mark your calendars to join us to think differently and Imagine the Supply Chain of the Future. We hope to see you there.

Please mark your calendars to join us to think differently and Imagine the Supply Chain of the Future. We hope to see you there.