Wang Laboratories. Eastman Kodak. Nokia. Blockbuster. Polaroid. Xerox. What do these names have in common? They were once strong brands that could not adjust fast enough to product shifts in the market. It hurts. These were once strong companies with bright futures, but they were rigid and inflexible. As growth slows, and global infrastructures mature, more and more companies worry that they too will make this list. They are trying to ensure that their names appear in history as “successes” not “brand failures.” They want “staying power.”

While the last decade was all about marketing and commercial processes, with the digital pivot, the supply chain matters now more than ever. The need is a supply chain that is more proactive, agile and flexible. Companies need shorter product cycles with easy customization. This needs to happen without deteriorating working capital or operating margins.

This is not today’s reality. Leaders struggle with the gaps; yet, ironically in the same breath, companies continue to talk about implementing best practices. They fund investments in legacy architectures (one ERP project after another). In many ways it is ludicrous. In the words of Einstein, “Insanity is doing the same thing and expecting different results.” In this post, I want to take a critical look at the current state, and share some advice for companies wanting to build successful end-to-end processes.

Current State

The journey should start with a definition. I define the End-to-End Value Chain as managed flows of products, cash, and information from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier as defined by the business strategy. It requires the definition of an operating strategy to enable the business strategy.

Today, when companies talk end-to-end, they are usually advocating the automation of flows within their four walls. It has little to do with the customer and the market which I think is a missed opportunity. It is usually cross-functional enablement for the organization, but not an end-to-end journey.

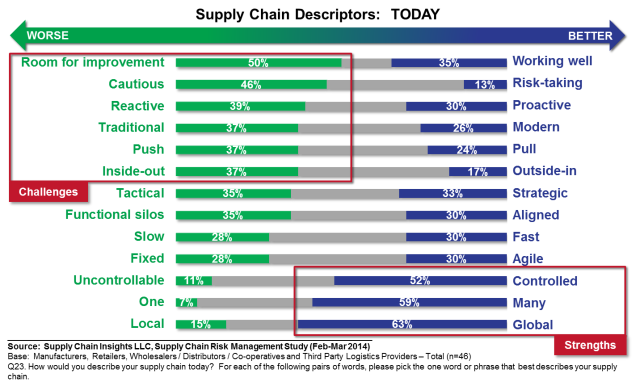

Companies are not happy with what they have today. In surveys, we get three responses to every one response that describes their supply chains as traditional, and reactive. There is room for improvement. Supply chains respond. They do not sense. The flows are inside-out. The current processes do not allow them to be outside-in. As a result, the supply chain is slow and out of step with the market.

The answer for many teams that I work with is to wave their hands and declare the need for an end-to-end supply chain strategy. They know they need to do something different. If they are lucky, they have leadership support.

It is not easy. There are many traps. It can be a guise to gain approval of a wish list of projects that cannot get funding. Or it is the next phase of ERP. As a result, I find the end-to-end project becomes a catch-all for the laundry list of projects parked from prior years. While the intentions are good, the results are not equal to the promise.

Figure 1. Supply Chain Descriptors

Building the Effective End-To-End Strategy

It happens at least once a week. On a call, the business leader states, “We are on the path to execute an end-to-end supply chain road map, and would like to get your insights.” I smile, and ask, “How do you define end-to-end?” There is usually push back and surprise followed by silence. In the depth of the silence, I feel like the caller wants to ask, “How can you be a supply chain expert if you do not know what end-to-end means?”

This is the dilemma. While companies believe there is opportunity in building an end-to-end strategy, there is no standard definition. Each company defines it slightly differently. Most companies finishing a large Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) project will speak about end-to-end, but really mean transactional efficiency.

I find that the path to building an end-to-end value network usually goes through five distinct phases: improving transactional efficiency, data sharing, formulation of policy, building relationships, and engaging in joint value creation (reference Figure 2). Companies that have cross-functional alignment and clear governance models can make progress faster. When source, make, and deliver report to the same organization, progress is quicker. Conversely, companies with traditional management believing in functional-silo mentality will have difficulty to move forward. I also find that traditional approaches like SCOR and APICS support functional thinking and do not enable the progress necessary to drive the End-to-End Journey. (In the spirit of transparency, I sat on the SCOR Council board for five years and tried to drive the SCOR model to be more holistic when I was at AMR Research, but to no avail.)

The leader will find that it is like running a decathlon. Why? The winner of the decathlon does not strive to win each event. Instead, they play to place first overall. Orchestrating the supply chain is similar. The company that plays to win does not strive to have the best manufacturing costs, or the best procurement practices; instead, the team focuses on winning together cross-functionally on a commonly held portfolio of metrics. I advocate a portfolio of growth, cost (EBITDA or operating margin), inventory turns, customer service (on-time and in-full shipments), and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). This drives markedly different behavior than when a manufacturing organization is incented on the lowest manufacturing costs with the highest Return on Assets. It requires leadership and alignment, and clear definition of goals.

In this process, the paradigms of project excellence and functional supply chain processes are detrimental. When companies optimize the functional response, they sub-optimize overall results. It requires education of the organization and a strong leadership to move past and orchestrate functional targets. When the leader orchestrates, the functional metrics are about reliability with all functions aligning against a common portfolio of metrics.

In the process, companies also have to challenge their conventional paradigms about technology. It is not about tight integration. Instead, it is about synchronization and harmonization of data. The value network needs systems that enable one-to-many and many-to-many data models with bidirectional flows. (This is not ERP.) Analytics are the secret sauce. The change happens the fastest when companies are aggressive on the adoption of new forms of analytics.

Over time, the focus shifts from supply chains to value networks. The most progress happens when there is alignment of the financial, commercial, and operational teams against a burning platform. To accomplish this goal, training on value chain concepts is necessary to align the commercial and operations teams to a common understanding. This is easier said than done: the organizational barriers are high.

Figure 2. Maturity Model for the End-To-End Supply Chain

Avoid Nine Mistakes:

In my discussions, I see these nine mistakes often. I share them to provoke new thinking and to help teams avoid a failure:

1. Goal Clarity. Build your End-to-End Journey with the end in mind. Be clear on the definition of ‘end-to-end’. Use the framework in Figure 2, to help drive the definition.

2. Build a Guiding Coalition. To make the shift, the path from a functional orientation to an end-to-end strategy is fraught with change management issues. There are many. Career paths are functional, and the shifts challenge traditional career ladders. Planners love their spreadsheets. Today, individuals operate in Excel ghettos with maverick behavior. Enlist the help from human resources and actively work the change management issues.

3. Orchestrate Cross-Functionally and Outside-In. Companies with the greatest progress have a common leader for source, make and deliver. These leaders orchestrate the trade-offs between functions with a focus on shared metrics. In the most successful organizations, the functional metrics are aligned to reliability while the corporate metrics are a holistic balanced portfolio. The processes are outside-in, focused on creating value for the customer. As a result, the end-to-end strategy flies in the face of channel loading, and end-of-the quarter shipments. Confront these issues early.

4. Avoid Buzzword Bingo. The client that I visited yesterday described their strategy as a new archetype that would enable an agile, proactive, and flexible response. However, when I asked for the definition of an archetype, I could not get one. When I asked for the definition of agility, or proactive, or flexible, I got blank stares as if to say, “Aren’t these words clear? Why would I need to define this more?” This is usually a major gap for the end-to-end strategy: there is no alignment on definitions. Without definition clarity, the project spins out of control going into different directions. The first step is to get clear on the project charter.

5. It Is Not About Customer-First. Customer expectations need to be grounded in what is feasible as a reliable, profitable response. I know that it may sound illogical, but companies that have a customer-first policy usually have a lower level of customer satisfaction. Great customer satisfaction should never hinge on heroics. It needs to be reliable, consistent and based on profitable policies. Ironically, customer service requires strong discipline. This is inconsistent with many commonly-held beliefs.

6. Define Regional/Global Governance. When it is not clear how companies make decisions, employees struggle to make progress and corporate politics abounds. It is the worst form of Muda. The first step in the journey is to define how the process will be governed. This needs to be defined along with the principles to be used to make decisions. Too few companies have done a good job at the definition of governance. Get clear and help everyone to understand how decisions will be made.

7. Embrace New Technologies. Test and Learn. The greatest value in end-to-end supply chain projects are fueled by decision support technologies, cognitive learning and visualization analytics. These are the infrastructures needed to sense, adapt and respond. They drive agility. These technologies do not come from large and entrenched ERP/APS technology providers. To implement these new technologies, companies need to adopt a test-and-learn strategy. The implementations are not straightforward (like an ERP project). To gain the greatest value, the projects require testing, adaptation, and process modification. Companies often make a mistake of treating these projects as traditional implementations; and as a result, they have a high failure rate.

This is a great opportunity to tackle the Bullwhip Effect as shown in Figure 3. Use new forms of analytics to sense and translate demand. Educate the organization on the concepts of demand latency, order flows, and downstream data.

Figure 3. The Bullwhip Effect

8. Protect Your Product. Think hard about the requirements for traceability, serialization, counterfeiting, and brand protection. Regulations are increasing the rules of the game are changing. Be sure that you are building the capabilities to protect your brand.

9. Define Supply Chain Visibility. Supply and demand visibility are key components of an end-to-end strategy, and today’s value network is held together through spreadsheets and email. It is not adequate. Map the locations of your second- and third-tier suppliers. Think hard about the definition of demand and supply visibility. As shown in Figure 4, realize that in the definition of supply chain visibility there are many components. True supply chain network visibility requires a business network. The most popular and relevant are GT Nexus, Elemica , E2open, and Neogrid. Don’t waste your time testing supply chain visibility concepts for the enterprise with EDI providers like IBM (acquired Sterling Commerce) or Open Text (now GXS), or the stalled efforts of SAP to make their Ariba assets relevant for today’s supply chain.

Figure 4. Elements of Supply Chain Visibility

It is late. I am tired. Sorry if I have rambled. These are my thoughts over a cup of hot tea after a week on the road. I would love to hear yours. Have a great weekend.

If you would like the opportunity to network with others on these topics, consider our public training in Philadelphia in June and August or our Supply Chain Insights Global Summit in September. We want to help supply chain visionaries around the world break the mold and drive higher levels of improvement.

____________________

About the Author:

About the Author:

Lora Cecere is the Founder of Supply Chain Insights. She is trying to redefine the industry analyst model to make it friendlier and more useful for supply chain leaders. Lora has written the books Supply Chain Metrics That Matter and Bricks Matter, and is currently working on her third book, Leadership Matters. She also actively blogs on her Supply Chain Insights website, at the Supply Chain Shaman blog, and for Forbes. When not writing or running her company, Lora is training for a triathlon, taking classes for her DBA degree in research, knitting and quilting for her new granddaughter, and doing tendu (s) and Dégagé (s) to dome her feet for pointe work at the ballet barre. Lora thinks that we are never too old to learn or to push for excellence.

Mistakes and Opportunities

Discussion of the barriers in moving from traditional planning platforms to build new processes on native-AI supply chain planning platforms.