As my arms stretch forward to pull for the next lap in the summer heat, three thoughts circulate in my head. (I often write my blogs in my head as I swim. The rhythm of a lap swim helps me to think better.)

During the swim, my mind races with many thoughts. Life for the supply chain leader is more complex.

- Shortages. Baby formula. Semiconductors. Tampons. Toilet Paper. Water. Wheat.

- Economics. Inflation. Recession. Gasoline. Commodity scarcity. Price of Ocean Shipping

- Business Continuity. Revlon. Target. The future inventory fire sale.

At conferences, I hear many discussions about risk management and control towers. These discussions make me laugh. The reason? The average discussion is a superficial treatment of a much more complex problem. Risk management concepts are largely passe, and control towers are futile attempts in the face of spiraling variability. (We cannot control variability. Instead, we need new approaches to sense, orchestrate and collaborate within organizations to improve outcomes.) Companies pushing IT standardization agendas will suffer the most.

We are living in a world of rich supply chain case studies. Each day, the Wall Street Journal features a supply chain failure as front-page news. The focus needs to quickly adjust from a cost-driven agenda to business continuity, but few can shift. Traditional processes accelerate the bullwhip impact leaving leaders chained and forced into reactive behavior. How do we break the cycle and free ourselves from whips and chains?

As I search for answers, three questions are top of mind.

Why Is There No Economy of Scale in Supply Chain Acquisitions?

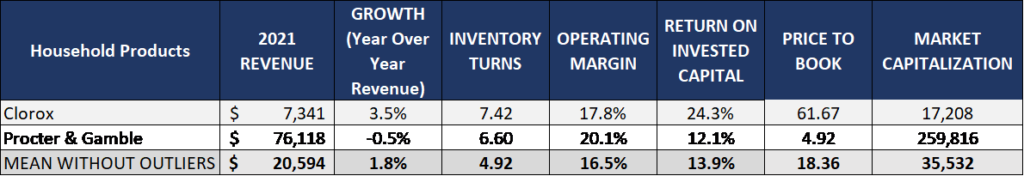

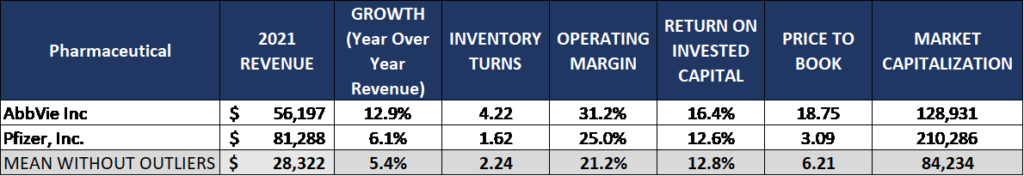

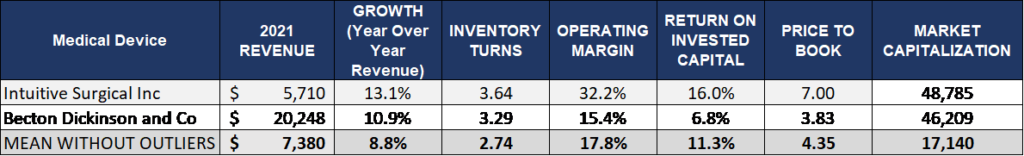

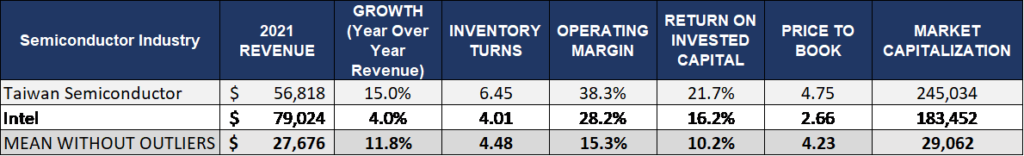

For the past eight years, each spring, I spend six weeks deep in the analysis of spreadsheets evaluating the corporate performance of supply chains by sector. I am attempting to understand the choices companies make and the impact on supply chain performance. It is a tall order: what seems so easy is very complex. (This report takes me about six weeks to complete.)

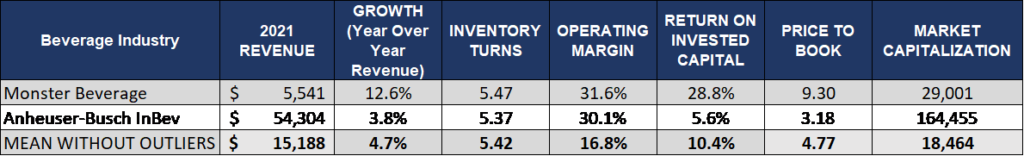

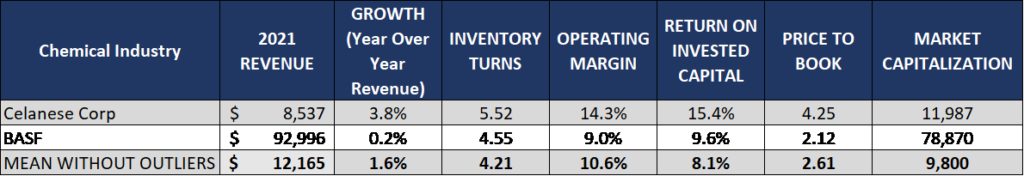

One of my stark realizations this year is that smaller companies are beating larger and often more established companies on the metrics of growth, inventory, margin, and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC). (In the analysis, we use this balanced scorecard to evaluate ten years of performance. The metrics selection resulted from work with Arizona State University in 2013. Our goal was to find the top four or five metrics that correlated with market capitalization.) Winners focus on margin, not a cost-based agenda.

While I do not want to give away all of the insights from the report, here, I share a comparison of the best performance within the peer group while sharing the results of a larger, more well-recognized competitor, along with the industry average. In the report, we study twenty-eight sectors. (Look for the full report next week.)

A cost-based agenda throws companies out of balance.

Larger organizations are more political and more focused on functional metrics. A focus on functional metrics degrades balance sheet performance.

The pattern is the same across the industries. My takeaway? Smaller companies are outperforming larger organizations. (Ironically, most supply chain leaders believe that the larger companies are the supply chain leaders to emulate.) The reason? I think the problem is the lack of organizational alignment coupled with the lack of clarity of supply chain excellence. When companies are focused on product and market innovation with a focus on channel performance, supply chain metrics improve. However, when the organization is marketing-driven, and sales and marketing operate in traditional silos, gaps grow in the organization, and balance sheet performance suffers.

Process latency (the time to make a decision) increases in the face of variability. Traditional processes increase process latency, as outlined in Table A.

Table A. Observations from the Supply Chains to Admire Analysis

| Outperforming Companies Are More Likely to be: | Underperforming Companies Are More Likely to: |

| Better aligned organizationally. | Embrace IT standardization. |

| Smaller and younger organizations. | Believe that traditional practices are “best practices.” |

| Product innovators in their sectors. | Reward functional behavior with less clarity on governance. |

| Driving process innovation agendas. | Be more dependent on services outsourcing. |

| Actively designing supply chain flows. | Have attempted to grow through M&A. |

| Focused on managing complexity. | Focus on tight integration of the budget to supply chain flows in S&OP. |

| Recognizing and managing supply chain flows based on rhythms and cycles. Not treating all products are treated the same. | Manage the supply chain as a homogeneous process—treating all items the same. |

Why Are We Letting Ourselves Be Whipped and Chained?

I spoke at an event in Silicon Valley this month. The room, brimming with excitement to reconnect after a long dry spell of business networking opportunities, openly discussed the current shortages in the semiconductor industry. As they bemoaned the fact that upstream trading partners share dismal forecasts, I laughed.

The reason I laughed? Why would they ever think the automotive industry would give them a good forecast? A fallacy in traditional thinking is that the use of a customer forecast will improve outcomes. Most customer forecasts are insufficient. My motto is trust but verify. (Model yours based on FVA analysis and understand the value.)

My question? Why are the semiconductor companies not modeling consumption? The data is available.

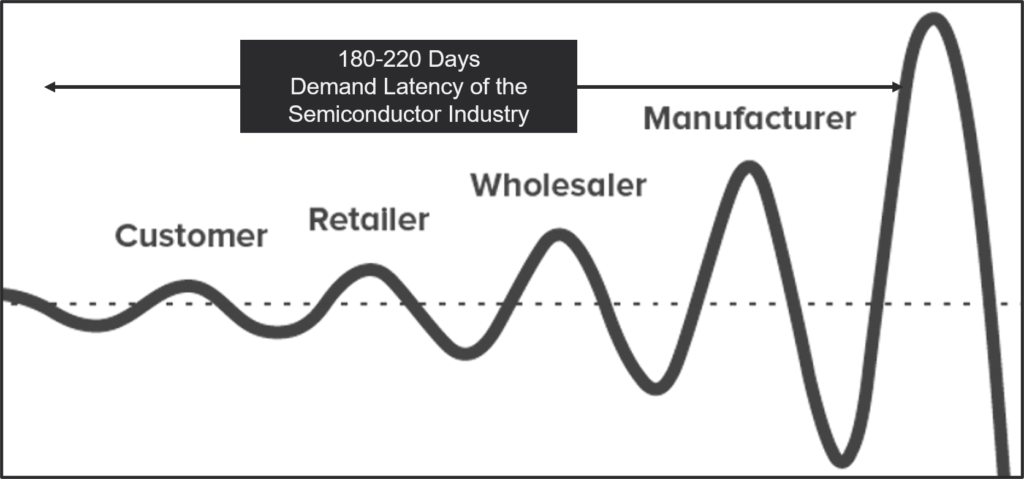

My second question is, “Why are all industries not modeling consumption patterns to manage backlogs in the face of the pending recession and inventory fire sale?” The assumption that traditional demand planning focused on order patterns or the use of S&OP to understand demand is insufficient. The further back in the Company’s supply chain, the more critical the modeling of consumption data.

I then told them about working with a Fortune 500 Chemical Company in 2007. During the great recession, the Company wanted to know if the economic upturn was going to be a W, a U, or a V? So I got a call to meet with the board and their team of seven economists.

When they asked me the question, I laughed and replied, “I sat on the back row of my Economics course at Wharton for a reason. You are far smarter than I.”

The follow-up discussion was on the bullwhip impact. The overarching goal was to know when to shut down the Company’s titanium dioxide factory. The demand latency to market consumption was 220 days. They believed that the order represented demand.

Due to safety concerns, the titanium dioxide plant was tough to start and stop. The product, a key component of white paint, was used in two primary markets—automotive and home improvement. So, I asked the group why they were not modeling the market using consumption data. They looked at me like I had two heads. We talked for an hour about order latency and how the order is a poor proxy for market demand. The concepts were foreign to them. (I find them new still to most supply chain leaders.)

As an outcome, we built a model of thirty market factors to model channel demand with minimal latency. The results were incredible. While we were rolling out the implementation model, the initiative was killed. The reason? Standardization of the IT platform. A major consulting firm got the ear of the board to reduce costs by rolling out an end-to-end SAP project. My learning? I failed to build a guiding coalition for change. Changing course requires building a team and redefining work at all levels of the organization.

Can Newer Forms of Technology Help?

Yes, I think so, but not without the redesign of work.

In the 1980s, we simplified models based on the limitations in technology model capabilities. We dumbed down the models, never expecting these simplistic solutions to be still sold in the market five decades later. I laugh with companies when they laud them as end-to-end solutions. They are anything but end-to-end. With each release of the Gartner Magic Quadrant for planning, I sigh. Such an old and outdated view of the market.

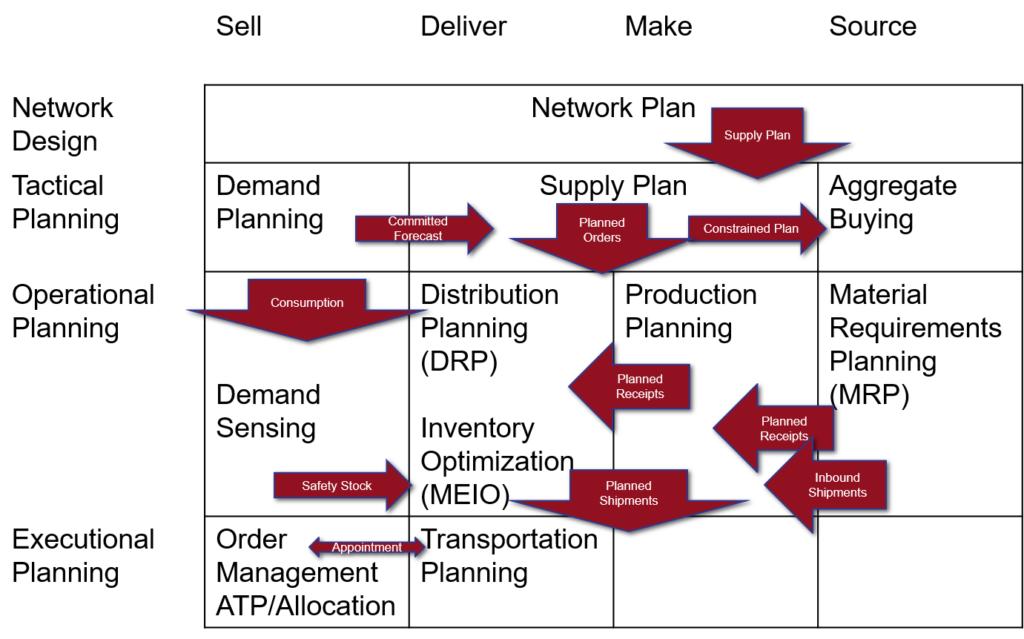

I also have a running debate with Peter Bolstorf, Executive Vice President of ASCM, on the deployment of technologies. He argues that companies have only deployed 30% of what they bought. He believes the answer is the implementation of shelfware. My response is increasing the deployment of traditional technologies is a distraction. The world will not be better through the implementation of more SAP APO or IBP or Oracle Supply Chain Planning. More of yesterday’s solutions are not the answer. To help the reader, I depict the traditional taxonomy in Figure B.

Figure B. A Traditional Planning Taxonomy

We lost our way believing that tight integration of transactional data would improve planning.

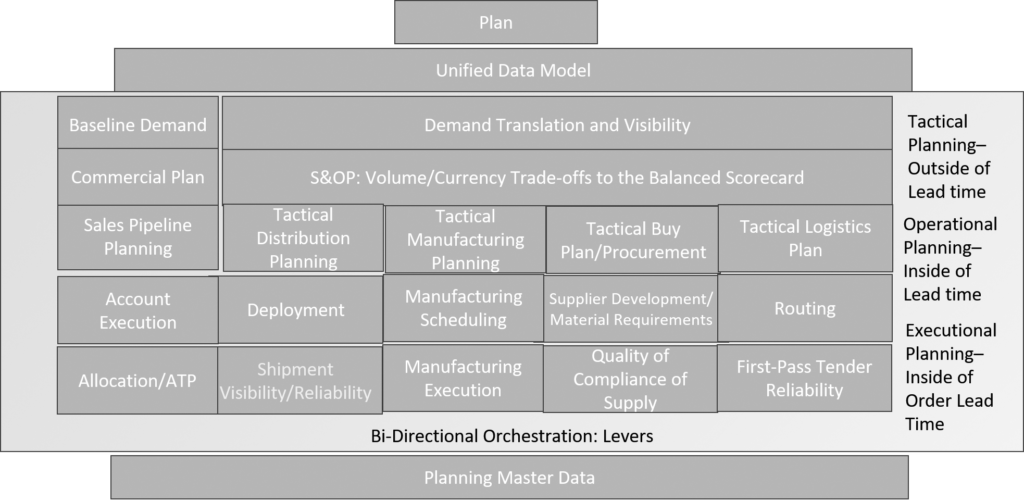

Instead, I think we need to architect solutions from the channel back, reinventing decision support. A unified data model is required to drive interoperability and collaboration of decisions across the different data models. (For example, DRP and TMS have nothing in common.)

The movement from relational database structures to graph and ontological modeling accelerates learning and the visualization of flow trade-offs. Simulation helps to test plan feasibility.

The planning master data layer is required to help organizations understand the best decision in the face of variability. This architecture representation in Figure C is an amalgamation of what I see happening in pilots with innovators in the market.

Figure C. Evolving Planning Architecture and Taxonomy

We are currently in the evolution of technology approaches. As a result, I encourage all to stop painting in the boxes of traditional technology boxes outlined in Figure B–and to start to refine the approach as outlined in Figure C. Redefining current models is not the answer.

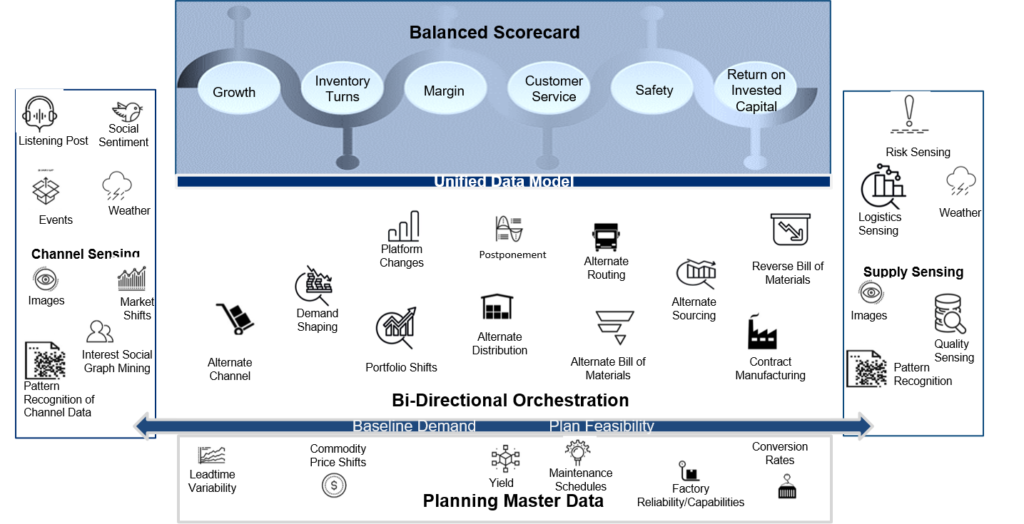

Instead, I think we need to rethink architectures to improve decision-making in the face of increased variability from the channel back while orchestrating market-to-market. The step-change cannot happen without the addition of a design element to manage flows while recognizing that companies have multiple supply chains and redefining the role of the forecast (from a focus on the error to embracing demand as a flow and ensuring bullwhip minimization in the process design) and inventory (from a focus on inventory levels to managing the form and function of inventory strategies). Figure D illustrates this thinking.

Figure D. Bi-directional Orchestration

Newer forms of technology offer promise. Simulation is easier and more flexible. Collaboration platforms enable the redesign of work. Newer forms of analytics allow no code capabilities for a unifying data model.

Unfortunately, only 4% of companies are innovators. Most blindly follow the pack of believing in historical practices and traditional technology approaches (which I think are legacy). I encourage you to be an innovator.

To take advantage of the technological advancements, I believe we need to redesign work. Why do organizations have hundreds of planners with over twenty titles? The planning organization is analogous to the typing pool in the roll-out of computers on business leaders’ desks. New solutions enable the democratization of planning. We need to use collaborative platforms to place the business models on the desks of leaders.

Wrap-up

With that, I will don my swimsuit and head back to the pool. We are in the middle of planning for the Supply Chain Insights Global Summit on September 6th-8th in Washington, DC. Swimming is excellent relief from stress as we plan the conference two months away.

The focus of the conference is on Supply Chain 2030. This conference has a physical presence for 90-100 business leaders at the Westin near Dulles Airport and a virtual component that will be facilitated on a virtual platform with guest speakers by Sarah Barnes Humphrey. I encourage all to sign up. We need to redefine architectures, but it needs to start with redesigning work. To do this, we must have a different discussion and free ourselves from whips and chains.