This morning my mailbox was bombarded with the news of a tentative agreement/settlement of the nine-month labor conflict between the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA) and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). The people on the ground–my contacts in the 3PL, freight forwarding, and transportation industry–know that the labor strife is only a part of the larger story.

This morning my mailbox was bombarded with the news of a tentative agreement/settlement of the nine-month labor conflict between the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA) and the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). The people on the ground–my contacts in the 3PL, freight forwarding, and transportation industry–know that the labor strife is only a part of the larger story.

The issues of chassis management, land-locked ports (currently gridlocked with little space), and the requirements for unloading larger ocean vessels confound a tough issue. Unloading at the western ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach have been an issue for many months. In my interviews, some say August. Others say February of last year…. Where they all agree is that the labor union discord was the icing on the top of a broken link in the supply chain. And, most report that the port authorities are sugar-coating the real issues. It is not trivial. The West Coast ports represent approximately 30% of total U.S. port capacity and are critical for Asian trade.

In 1971, there was a 134-day strike at the West Coast ports. Slowdowns, lock-outs and work stoppages occur on a regular basis–almost every five years. We recover. This is not what worries me. I think the larger issue is the design of the ports to carry the volume. As a country, I think that we need to rethink supply chain flows for chassis, drayage and the unloading of larger ships. In 1971 the recovery from the work stoppage was smoother than this will be.

We will get through the labor problems, and they will reoccur; but, I think that we are dealing with a much more insidious issue. The port infrastructure is not equal to the challenge of moving the high levels of freight of larger ships without rethinking unloading space, equipment and flows. When today’s big ocean containers come to port, the instantaneous need for chassis is high. It takes 2 to 3 days to unload a ship. Today, the number of chassis required for a ship is between 2,000 and 5,000. (The chassis is underneath the APL container in this picture.) The ships are getting larger. Chassis ownership issues abound, and movement is grid locked. In 2018, the Journal of Commerce reports that a ship will have 22,000 to 24,000 twenty-foot containers in 2018. For the supply chain leader, this means the flows will get lumpier, less predictable, and even more variable.

Over the last decade, the size of ships has gradually increased putting pressure on the instantaneous rate to unload. The ports were designed for 1980s flows. As the ships get larger, the ports become more and more constrained–this is particularly true for the west coast ports of Long Beach, Oakland and Los Angeles.

Today, the number of inbound vessels at sea, lining the horizon at the West Coast ports, is climbing. The ships stretch across the horizon two and three layers deep in Long Beach. Getting a port like Long Beach–with issues since February, 2014–to recover following the work slowdown is going to take a LONG TIME. As a result, supply chain leaders need to take action to re-shore where possible, and relocate manufacturing and supplier relationships. This is going to get worse before it gets better.

With the rise of the global multinational, Asian flows are essential to today’s manufacturing operations. The leader of today’s supply chain lives in an interconnected, tightly-woven world. The flows assume that transportation can move without an interruption. Today, this is not a valid assumption, and most manufacturers lack the inventory buffers for inconsistent flows.

Shipping will not return to normal at the West Coast ports for a LONG time. And, when the dust settles, I think that we will have a new normal. It is one that most companies are not ready for….

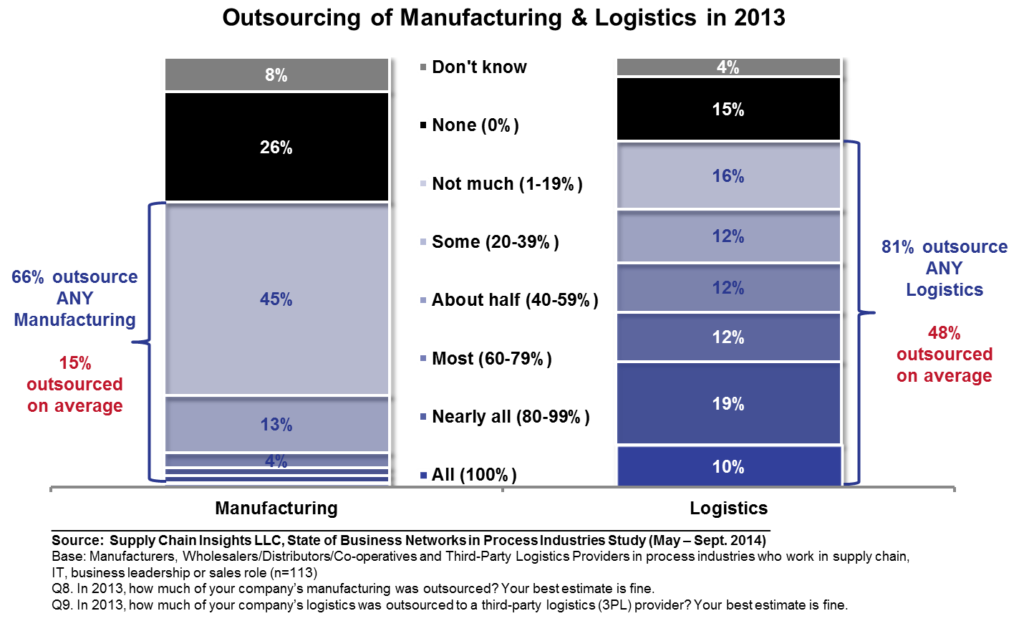

It is my hope that the port authorities stop sugar-coating the real issues. Before the labor issues heated up in December-January, customer clearance was delayed at least one month with increased variability. It is going to get much worse before it gets better. Beware: this labor agreement is not a panacea and as seen in Figure 1, this issue is the cross-hairs of modern supply chain trade.

What do you think? How are you preparing? I look forward to your feedback.

I hope to see you soon in my travels. On March 16th-18th, I will be on a book tour in Europe discussing the concepts of Supply Chain Metrics That Matter. The following week, I am speaking at the Ortec, Optimus Event in Atlanta, the RIS News event in Orlando, and the Demand-Driven Institute Event in Houston.

Lora Cecere is the Supply Chain Shaman. With over 15 years as an industry analyst, nine years building and selling software, and twelve years of managing operational supply chains for companies like Procter & Gamble, Clorox, General Foods (now Kraft) and Dryer’s Grand Ice Cream (now Nestlé), Lora writes for the supply chain visionary. She is known for making the complex simple and writes in a no-nonsense, straight-talk writing style.

As a consummate writer, Lora strives to write 5, 000 words a day. You can read her commentary as a Linkedin Influencer, a contributor to Forbes and monthly reports as the founder of Supply Chain Insights. When not knee-deep in supply chain research, Lora loves to quilt, knit and dance. She has calloused feet from her new pointe shoes at ballet, and sports a wearable on her wrist as she trains for her upcoming triathlon.

Beyond Rabbit Ears on a Black & White TV

When I was a young girl, we received one television channel. Rabbit ears on top of the TV helped us get more channels. We loved