Yesterday morning I was sick. In the early morning, in a hotel room in Antwerp, I crawled to the bathroom and groaned as my body expelled what I think was food poisoning. The body is amazingly efficient in getting rid of what is making you sick.

Feeling very green, I stumbled through the airport and found my way to my seat on the plane from Brussels to Philadelphia. <The joys of international travel.> While I wanted nothing more than to close my eyes and sleep, the stewardess came down the aisle with a stack of newspapers. Mindlessly filling time, I flipped through the paper until I landed on an interesting article on the impact of e-cigarettes on the body. The question in the article was “Is vaping safe?” The essence of the article was that the leading expert on smoking, Johanna Cohen from John Hopkins, in USA Today bravely admitted that after four years of research that she did not know. I clipped her explanation and put it into my purse. I found the writing beautifully described my dilemma:

“The degree of uncertainty isn’t what makes science weak. It’s what makes science strong. You see, science doesn’t happen with the flip of a switch, but rather arrives incrementally as if by dimmer. It’s only completely illuminating when we’ve fully turned the knob. And, the truth be told, we’re never done turning the knob.”

I think of myself as a scientist. A researcher of sorts. When I started the work that I do at Supply Chain Insights, I termed myself an analyst; and while everyone wants to put me in the consulting bucket, I resist. To me a consultant works with a company on a project basis to implement processes or technology. I, on the other hand, am trying to figure out what defines supply chain excellence. I invest 25% of the proceeds of my small bootstrapped company into quantitative and qualitative studies to understand trends in supply chain excellence and gain insights on the views of business leaders.

In this journey, Johanna Cohen’s concept of the “dimmer” spoke to me. The research I am working on started as deductive–with a set of fixed hypotheses and a clear objective function. Over time, it has morphed. Today it is inductive–where I let the data speak for itself. As I age, I admit more and more that I don’t have the answers.

When I started Supply Chain Insights, I hired a specialist in consumer research to help me; and over time, I have gained great joy in the design of surveys. While I am not as good at the design and coding of the surveys as my research expert, Heather Hart, together I think we make a good team. Over the past nine years, I have learned a lot on how to design a survey. The work that we do is exciting, and slowly, like turning the dimmer, I think that we are making progress.

In the larger business world our work is not well understood. It is a new company with a new business model. We invest in research and give it away freely. People scratch their heads. We are mavericks.

The commercial model of the company is to make money through speaking, research studies for others, facilitated workshops, benchmarking, training, and events. The problem is that there are many– consulting companies, technologists and consortia– that term their work “research” and preach best practices. I find most to have opinions, but little research. There are many pundits and I think that we do not have “best practices.” Instead, I think we have emerging practices. I feel we need to apply research methods to gain an understanding of the future state.

In Figure 1, I share the work that we are doing at Supply Chain Insights. At the end of three and a half years, we have finished 55 research studies (It will be 58 at month’s end.), published 76 reports, and sit on we sit on 4,794 responses (It is 5,500 at month end.). We take research seriously. I think this why the newspaper clipping speaks to me so vividly.

Figure 1. Research Efforts of Supply Chain Insights

The research that I am doing is very different from that in academia. Academia looks to history and public citations as research. It inches along very slowly. In my work at Temple, to complete my Doctorate of Business Administration (DBA), in the last year I immersed myself in the world of academia. I have tried to do deep literature searches on the academic supply chain research in the journals. My struggle is that the field of supply chain is relatively new and the research is very limited. It is weak. The body of research in academia is not up to the standards of other fields like finance, corporate strategy, or marketing.

There are also strange nuances. As the supply chain field matures in academia, oddly, supply chain has found itself as a strange bedfellow with marketing. Ironically, while great gaps exist between supply chain alignment and marketing in the world of manufacturing, in most schools, supply chain management is a field within the business school often reporting to a marketing head.

Over sandwiches a couple of days ago at the OM Partners event in Antwerp, I spoke to a supply chain leader who I admire. She is serious about training her team on supply chain concepts and encourages all of her team to take the APICS certifications. Convinced she needed to do the same, she took the certification herself. Her dilemma was that she found the materials old. Her comments were, “APICS is out of date. I need a source of supply chain insights that is current.” This is what we are trying to provide in a no-nonsense, open content research-based forum. I offer the research freely to both APICS and CSCMP, but find each of the organizations immersed in their own issues. I cannot change the world, but I would like to be the dimmer switch that can slowly help supply chain leaders understand how to drive supply chain excellence. This is why we are launching our new community, Beet Fusion, on October 15th.

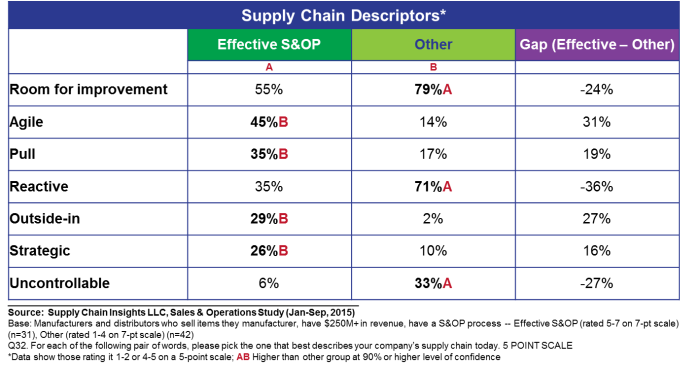

Let me give you an example. Many people ask me, “What is the value proposition for Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP)?” I have tried to answer this question many times and in different ways. One of the most interesting projects that we recently completed is a study where we asked companies to self-assess their S&OP processes on a scale of 1-7 based on perceived effectiveness. When we group the responses by Effective S&OP responses (scores of 6-7) versus those that Do Not Feel That They Have An Effective S&OP (1-5), we see distinct patterns in how they describe their organization. In Figure 2, we share these differences:

Figure 2. Characteristics of Effective S&OP

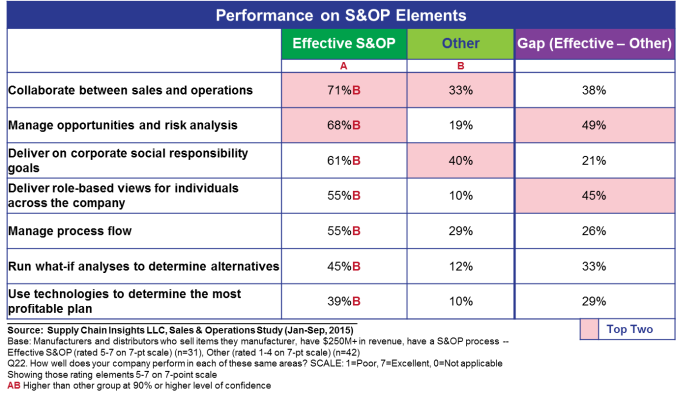

So, would you like to work on a program that could help and organization be more agile, strategic, and more in control? A program that could help companies be less reactive? The answer is an effective S&OP (with a 90% confidence level). However, what defines an effective S&OP process? Companies rating themselves with stronger capabilities are more likely to use supply chain planning systems, are more likely to be able to produce a feasible plan in supply planning, and use “What-If Analysis.” We find that it is not one, it is many elements. One thing is clear for me, it does not happen without the use of planning technologies.

Figure 3. Characteristics of Effective S&OP

Over coffee last week, I asked a supply chain leader to comment on what makes a successful supply chain planning organization? His response, “It is inverse to the number of spreadsheets. Some of my planners have 500 per person. My goal is to minimize this number.” I agree.

So, in closing, I want to thank all of my readers for helping us on our journey. It is our goal to write thought leading research to help the industry, and with your help, I think that we are making progress. We think that we are shedding light on an important subject…

About the Author:

Lora Cecere is the Founder of Supply Chain Insights. She is trying to redefine the industry analyst model to make it friendlier and more useful for supply chain leaders. Lora wrote the books Supply Chain Metrics That Matter and Bricks Matter, and is currently working on her third book, Leadership Matters. As a frequent contributor of supply chain content to the industry, Lora writes by-line monthly columns for SCM Quarterly, Consumer Goods Technology, Supply Chain Movement and Supply Chain Brain. She also actively blogs on her Supply Chain Insights website, for Linkedin, and for Forbes. When not writing or running her company, Lora is training for a triathlon, taking classes for her DBA degree in research at Temple or knitting and quilting for her new granddaughter. In between writing and training, Lora is actively doing tendu (s) and Dégagé (s) to dome her feet for pointe work at the ballet barre. She thinks that we are never too old to learn or to push an organization harder to improve performance.

Beyond Rabbit Ears on a Black & White TV

When I was a young girl, we received one television channel. Rabbit ears on top of the TV helped us get more channels. We loved