Supply chain excellence is easier to say than to explain.

Business leaders are action-oriented and competitive. Executive teams strive to drive improvement in supply chain results; yet, sadly, only four percent of public companies succeed. The reason? After two decades of study, I think because it is a lack of understanding. In this area of research, I find that companies are like dogs chasing cars. The grass is always greener at another company. The promise of a well-intended consultant just sounds sooooooo good. Or the organization chases bright and shiny objects. Companies struggle to maintain focus and drive discipline to build balance sheet results.

The supply chain is a complex non-linear system. At each company, there is a relationship between the metrics of growth, margin, inventory, customer service, and asset strategy. (For the purpose of this article, I will use Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) as the proxy metric to discuss asset utilization.) Understanding this relationship requires modeling. (A potential value of a digital twin.)

I term this relationship between metrics and capabilities as the company’s Effective Frontier. Because of these inter-relationships between metrics and capabilities, if a company pushes a single metric, the company’s performance in other metrics is thrown out of balance. In short, the individual metric will improve, but the performance on other metrics may suffer.

A Case Study

Let’s take P&G as an example. In the 1990s, Procter & Gamble (P&G) was an undisputed leader in consumer products. Now, I view the company as a supply chain laggard. At P&G, processes move slowly, and convention reigns.

The P&G culture is dominated by leaders with long tenures. In this respect, the company is insular and risk-averse. While there is much that I admire in the culture, there is little turnover or understanding of cultural diversity. The culture is dominated by “lifers” and technology investment is conservative. The company transitioned from an innovator in the 1990s to a late adopter in the last decade.

In 2011, Yannis Skoufalos became the Global Product Supply Officer at Procter & Gamble. Yannis transitioned from the role after eight years in 2019. His focus was cash-to-cash.

Prior to Yannis, Keith Harrison was the Global Product Supply Officer for slightly more than ten years. Keith led the work to move P&G from a regional to a global manufacturer opening up the Warsaw center of planning excellence and outsourcing IT to HP. Keith was an undisputed leader in building talent to drive manufacturing excellence.

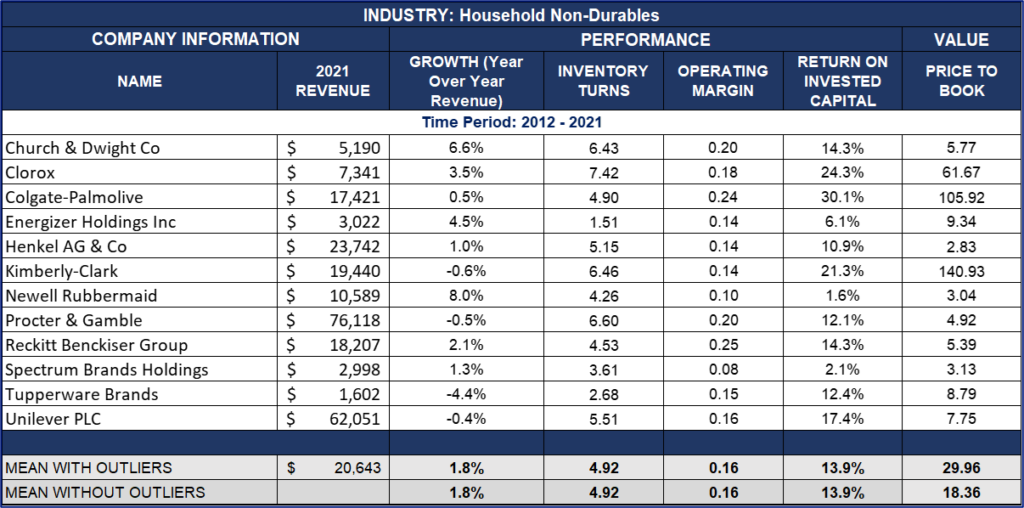

When we compare the results of P&G to its peer group for 2012-2021, P&G outperforms in inventory turns and margin but underperforms in growth and asset utilization. Was this by design? My answer is no. My reasoning? The most significant discussion in the P&G annual reports centers on growth.

In this period, P&G attempted to grow through acquisition. The company invested in multiple beauty brands and sold off food products. The results are questionable. Each M&A activity was painful for the organization. The details:

- 2001-Acquired Clairol for 4.9B$

- 2002-Divestiture of Jif and Crisco to Smuckers–813M in Stock

- 2003-Acquisition of Wella for 7B$

- 2005-Merger with Gilette for 57B$

- 2008-Purchase of Nioxin for 300M$

- 2009-Purchased Art of Shaving for 60M$

- 2009-purchased ZIRH for 40M. Discontinued in 2011.

- 2011-Divestiture of Pringles to Kellogg for 2.7B$

- 2014-Sale of IAMS to Mars for 2.9B$

- 2015-Sale of 43 P&G Beauty Brands to Coty for 12.5B$

As shown in Figure 1, the results for the period of 2012-2021 tell the story. In this time period, smaller players like Clorox and Church & Dwight Co outperformed P&G. My take? P&G spent a lot of money to not grow.

Figure 1. Table of Performance

Throughout the decade, the company was marketing-driven not market-driven. Despite having point of sale data for the majority of regions and channels, the company continued to manage the supply chain based on traditional investments in Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) and conventional planning technology approaches. The company assumed that the order was a good proxy for demand despite the investment in the beauty category where demand latency is 5-6X that of laundry products.

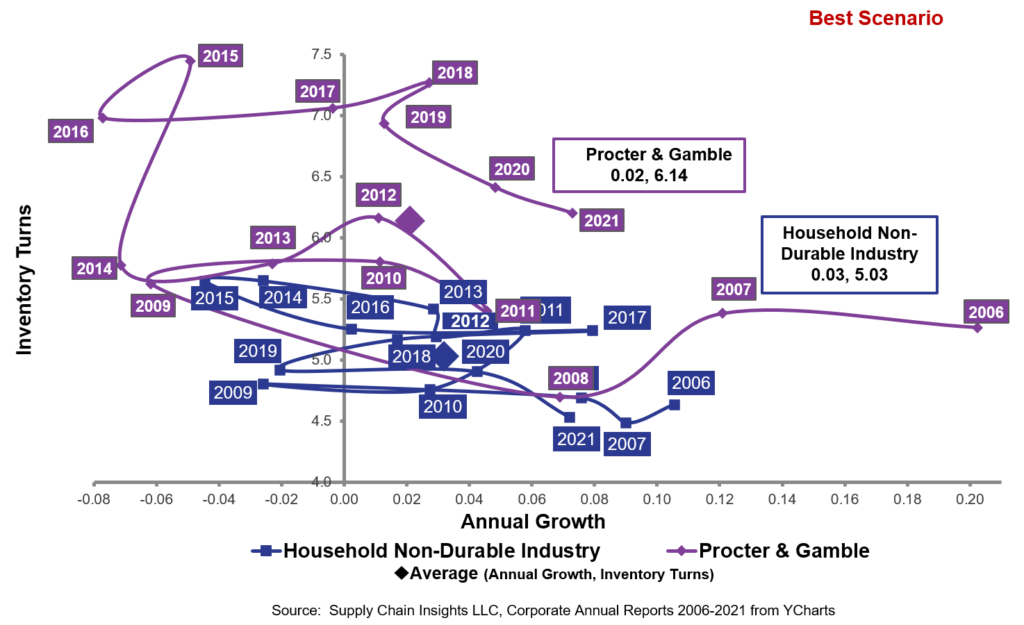

While the company’s investments in manufacturing scheduling and demand sensing improved outcomes, the organization under-invested in direct procurement solutions, tactical manufacturing planning, and network design. Supply chain excellence was largely defined as manufacturing excellence. Shown in Figure 2, we track the results for the period from 2006-to 2021. (Note the significant market volatility in the sector.)

Figure 2. Mapping the P&G Effective Frontier

Lessons to Learn

I tell the story to emphasize three points. Let me tell them through stories.

Lesson #1. Manage the Supply Chain As A Complex System. In the period 1995-to 1999, I supported a sales team as an employee of a supply chain planning technology company. I built value cases for sales. To calculate the benefits of the potential value of implementing a planning system, I benchmarked companies to their respective peer groups. My failure was three-fold:

- In this analysis, I never benchmarked companies to the industry averages. I had no idea of the volatility in each of the industry sectors (as shown in figure 2). I thought that the industry averages were fairly constant. They are not.

- The analysis was too short-term. My analysis only considered three-year averages. Supply chain performance analysis should be at least five years to reduce the variation from industry movement (noise) in the system.

- I never calculated and accounted for the inter-dependencies between metrics. My analysis never embraced the concepts of the effective frontier.

Lesson #2. Accounting for Economies of Scale. Logic and history would support that companies should be able to achieve economies of scale in their supply chain. However, history is showing that larger companies fair far worse than small and more focused companies. The issue is the management of complexity. A case is not a case. A manufacturing capability is not ubiquitous. So, while companies can achieve economies of scale in administration, sales, and logistics, the economies of scale for make, source, and deliver only happen when companies aggressively manage complexity.

Lesson #3. Blindly Accepting a Company as a Leader. When I worked at AMR Research in the period of 2005-to 2011, I blindly accepted that P&G was the industry leader. I failed to do enough analysis to understand that the leadership of P&G threw the company out of balance by a focus on functional metrics and an over-emphasis on inventory management and cash-to-cash. My learning? Dig deep. We cannot assume. The market deserves due diligence. True leaders top the chart on the balanced scorecard of growth, inventory turns, operating margin, ROIC, and customer service. Against this scorecard, P&G failed. However, I would allege, that P&G’s failure was supported by many consultants, technologists, and business leaders that made the same mistake that I did. It is for this reason that P&G is at the top of the Gartner Top 25. Should they stay? This is for the industry to decide.