Supply management. Supply chain management. Supply chain planning. Are these terms the same? They sound similar, but do they describe similar capabilities? The answer is no.

What do they have in common? Not much.

When deploying enterprise decision support applications, there are many implementations and lots of hype but few clear and consistent definitions. The lack of interoperability between decision support platforms is a problem for companies attempting to improve decisions from the channel to supplier bi-directionally through technology. While we speak of Artificial Intelligence (AI) enablement and better engines (think math) within existing systems, few question why we cannot drive an end-to-end signal across decision support frameworks. As a result, current deployments are analogous to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Why It Matters

Q3 earnings reports continue to make headline news. The public markets are nervous. FactSet reports that 66% of companies in Q3 2023 beat revenue guidance. The market is punishing those missing the mark. The issue is cross-industry. Today’s headline news includes AllBirds, Boeing, Canada Goose, Chemours, EMC, Hanes Brands, Fisker, Ford, Krispy Kreme, LKQ, Ryder, Tesla, Timken, Tyson Foods, Weight Watchers International, and WestRock. Q3 is a tough quarter: the list of companies failing to meet revenue guidance will continue to grow.

The question is, how can a company not meet guidance? The market tolerates an underperforming company that meets guidance more than a top performer that misses guidance. The essence of the question is resilience and the ability to forecast in a variable market reliably. For most, this is a market opportunity. This gets us to the question of what is the role of the forecast?` And why cannot we not do better with current technology deployments.

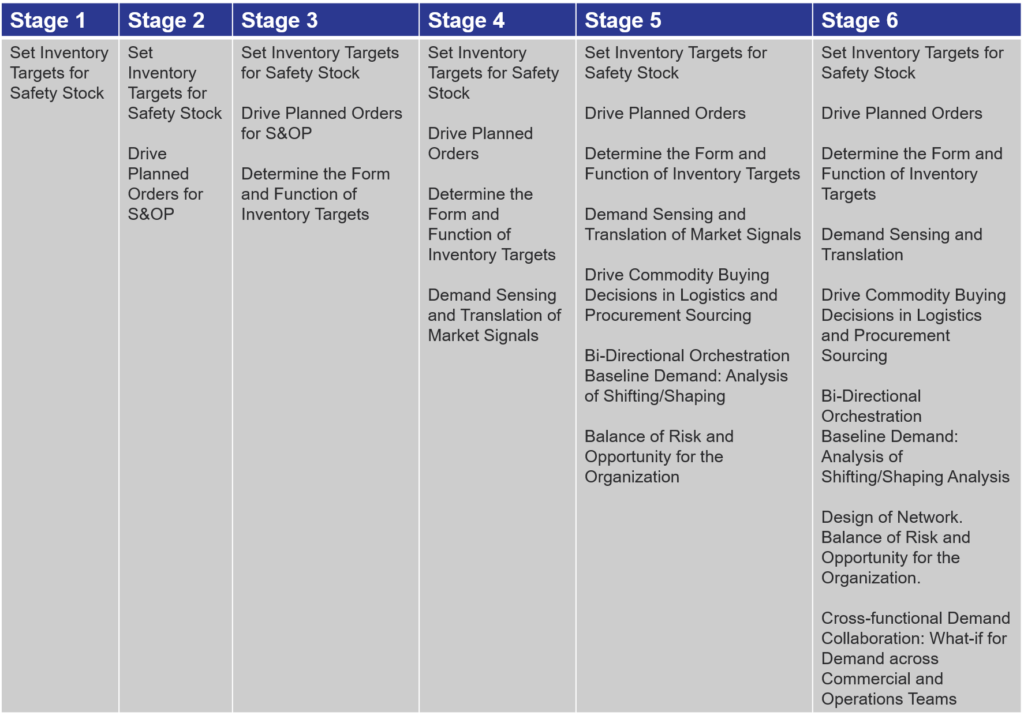

For most, forecasting is a conundrum full of potholes, politics, and bias. I believe demand is a flow based on the combination of products/services/customers and channels, as shown in Table 1. My Point of View (POV): current processes and technologies are insufficient.

Table 1. Increasing Maturity of the Role of the Forecast for the Supply Chain Leader

This gets me back to why technologies are not improving enterprise leadership’s ability to forecast and manage revenue. Or margin. PWC’s Digital Trends in Supply Chain Survey reports that 83% of manufacturers say that supply chain technologies have not delivered the expected results. This exceeds the 55% previously reported in the Supply Chain Insights surveys. For this blog post, never mind the comparison. Let’s not quibble on the percentages. The trend is clear. Let’s zoom to the bottom line: the results are less than optimal for all the monies spent and practices deployed.

In the PWC survey, the focus for the supply chain leader for the next 12-18 months is cost reduction, which raises questions for me and makes me sad. Based on the Supply Chains to Admire analysis, the first question is: Why do the cost reduction strategies not translate into operating margin improvement against peer groups? The second is, Why are companies focused on traditional risk management investments primarily focused on supply/procurement when the more significant opportunity is balancing risk and opportunity in an increasingly complex world?

Which gets me to the question, “What is supply chain management? And, how do we improve reliability when supply chain planning and supply management do not interoperate?”

A Story

I was driving a couple of weeks ago and got an urgent call from a long-time friend. For context, let’s call him Dave. He provides services to companies on master data management and is more familiar with transactional processing than decision support. When he speaks of the supply chain, he means procurement. This is his world. He does not know that this is his paradigm, but it is. Likewise, when he speaks about the supply chain, his partner, Yossi, his mental model is logistics. These are very different views of the supply chain. And isn’t it amazing that everyone is an expert, but no one questions their paradigm?

Through his work on standards recently, Dave attempted to collaborate with ASCM to educate the market on using authoritative identifiers. (For reference, authoritative identifiers are the starting point for processes where goods are tracked against a standard like fair labor or food safety. Consider social security management in the United States without a social security number. A social security number is an authoritative identifier. Today, we lack authoritative identifiers for products, companies, and locations.) Most brand owners have been slow to adopt and understand the need for standards. For example, only 22% of medical device products complied with GS1 standards during the pandemic.

Dave is currently working in the Middle East to try to improve track and trace and is struggling to define the supply chain. Frustrated, Dave exclaimed, ” Supply chain cannot be about everything. The conversation starts with the channel when I speak to the Saudis and discuss the scope of work. A supply chain is never about sales and marketing processes, right?” I laughed. For me, supply chain management starts with the channel and aligns enterprise decisions/behaviors to maximize opportunities and mitigate risks. (This is not the case for supply management or for Dave.) He had never questioned the difference. The takeaway? We can never have great discussions unless we are clear on definitions.

So WHAT?

As part of my blog series on definitions– leading to the release of my YouTube series and report on outside-in processes next week–here, I explain the differences. I will also elaborate on the potential opportunities to redefine planning platforms. We must learn from the past to unlearn to improve outcomes.

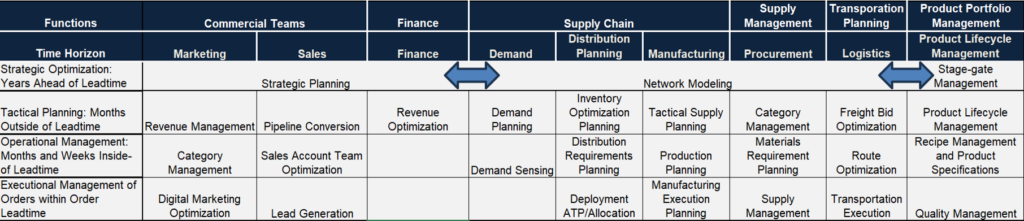

Across the organization, many forms of decision support do not interoperate. Over the last two decades, as shown in Table 2, we have automated functions but not driven workflows across processes to improve collaboration across dissimilar applications. I learned the hard way. I attempted and failed to:

- Use Point of Sale Data in Supply Chain Forecasting. Most supply chain models are “ship from” models based on orders. A Point of Sale forecasting system requires a “ship to” model based on the channel.

- Synchronize CRM and Supply Chain Forecasting. The models are too different to drive a clear signal from sales activity to demand planning in the supply chain.

- Align Transportation Planning and Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP). Again, these two very different and distinct models connect only to order management in the executional decision support window. Transportation management focuses on price/lane/routing assignments, assuming logistics availability, while DRP translates product volume into deployment logic based on the translation of demand.

- Couple Price Management or Trade Management with Supply Chain Forecasting. The lack of a clear determination of baseline forecasting (market demand with no demand shaping) makes this impossible.

- Connect the Output of Supply Chain Planning Supply (planned orders) to Procurement Commodity Management. Buying strategies need to be defined, and the interface needs to be bi-directional. The trade-offs of manufacturing and supply constraints are not visible today.

As a result, we continue to run multiple decision support engines across an organization that don’t align. These traditional approaches optimize a function within the organization. The result? Functional optimization throws the complex, non-linear solution termed supply chain out of balance, sub-optimizing margin and increasing risk.

Table 2: Different Forms of Decision Support Across An Organization

As a side note, when you look at the table, you might ask, where is Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP)? I find S&OP charted differently by company. (As a result, I have consciously left it off of this chart.) It should fall under network modeling as a layer above the traditional supply chain planning applications. I know this is contentious, so I left it off deliberately.

Supply Chain Planning and Supply Management are different forms of decision support. Supply management focuses on defining direct material requirements, whereas supply chain planning outputs drive planned orders to improve manufacturing cycles and outcomes. The two platforms connect at the Materials Requirements Planning (MRP) layer in Enterprise Requirements Planning (ERP). This is not sufficient to maximize opportunity and mitigate risks.

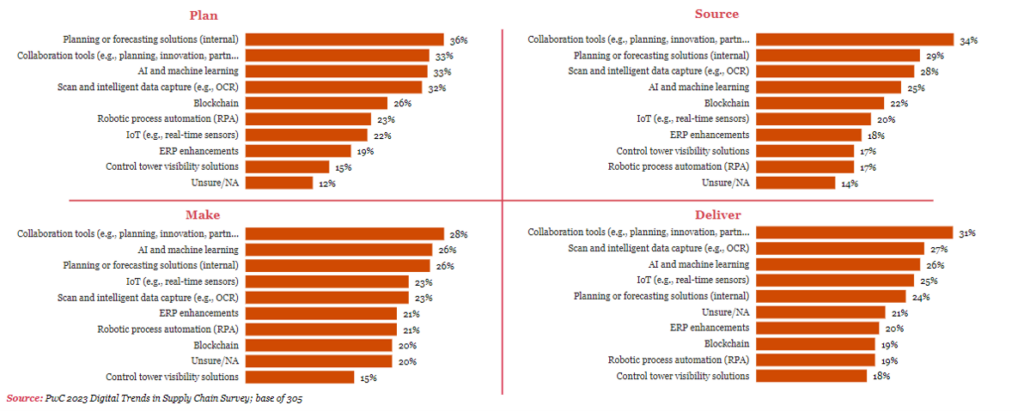

As a result, in the Price Waterhouse Study, companies have very different plans for technology investment for different areas of the supply chain as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Planned Technology Deployments

In addition, the supply management taxonomy stack is immature for direct materials. Over the last decade, most of the focus in supply management was on indirect sourcing. As a result, for most organizations, managing direct materials in an organization is a black hole driven by custom applications. In deployments, data issues abound. Most of these decision-support applications spin based on different planning master data assumptions.

Manage Planning Master Data to Improve Variability

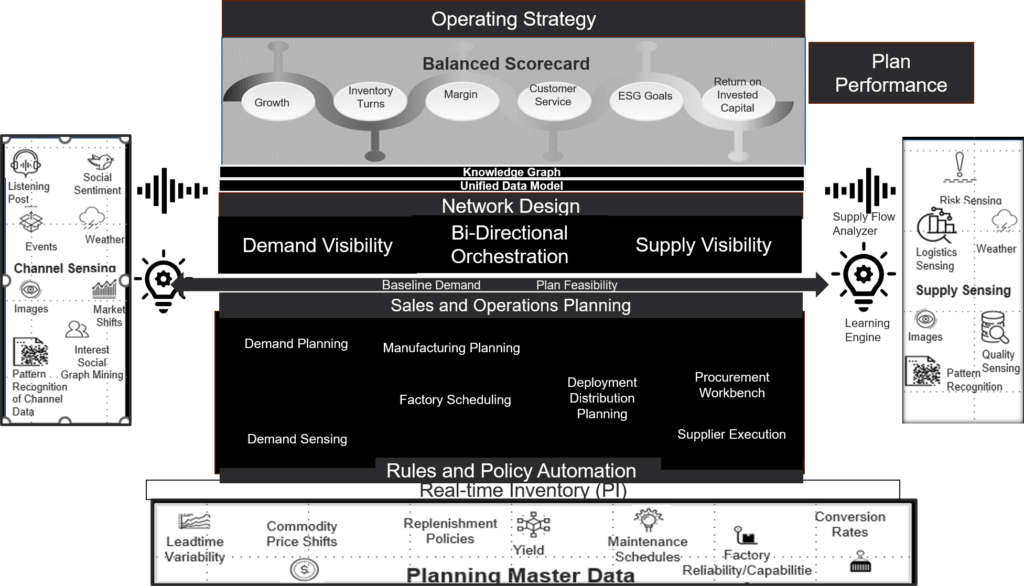

While traditionally, companies focus on transactional data cleanliness; few companies have a master data system to inform and improve decision support software. Note the definition of the planning master data layer in redesigning these flows in a future view of outside-in processes for bi-directional flow against a balanced scorecard to drive bi-directional orchestration.

Figure 1. Taxonomy of A Potential Solution to Drive Cross-functional and Bi-Directional Flow Across Flows with a Planning Master Data Layer

Supply Chain Management

I think that we need to have a mea culpa moment. Functional optimization does not drive revenue or margin performance resilience for a manufacturing or retail company. A focus on traditional optimization does not improve market capitalization. A focus on cost may throw the supply chain out of balance, increasing the total cost. The direct connection of financial data (which is more linear than supply chain data) to supply chain planning without a planning master data layer increases confusion without driving clarity.

What to do? Learn from the past to unlearn to rethink applications. The tight integration of decision support to ERP makes organizations less resilient and more fragile; yet, we do not have a well-defined platform to connect and translate channel data from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier. This journey starts with understanding our own belief system and questioning our paradigms.

Good luck if you are in the market seeking an end-to-end planning system. It does not exist.

When it does, we can forecast revenue better and manage margin. Until then, we are myopically attempting to improve functional costs. This is analogous to moving deckchairs on the Titanic.

References: 2023 Digital Trends in Supply Chain Survey: PwC