For the past three weeks, I attempted to move my fingers on the keyboard, but to no avail. With the mounting devastation in Ukraine, my heavy heart is a roadblock to writing. My brain struggles to communicate with my fingers.

War. War. War. The images flash in my brain as I close my eyes. When I turn off the news coverage, they remain—a haunting view of humanity gone wrong.

As I spent the time reflecting over the last three weeks, the number of articles streaming into my feed on supply chain implications was high, but I found most of them wrong. Some stated that the war marks the end of the global supply chain. My response is “Hogwash.” Corporations serve international markets, and some materials are available only from specific countries. An example is rare minerals (so critical for the evolution of the green supply chain) that are primarily sourced from Asia. By definition, this requires a global supply chain.

Others argue the demise of global sourcing; might I add caution? Supply chains are fit for purpose and asset-intensive. The relocation of assets and scaling equipment is not a flick of a switch. Yes, while I believe that we will be more choiceful on sourcing strategies and hopefully not blindly chase labor arbitrage or tax-efficient supply chain strategies, global supply chains will persist. I think that we are having the wrong discussion. My belief? We need to embrace variability. It is here to stay and will grow. The answer? Technologies and processes need to change.

Embracing A New Level of Variability for the Supply Chain Leader

The disruption in Ukraine adds a new layer of variability and complexity to an already complicated world with many levels of disruption. COVID, inflation, climate change, and the Ukraine war are each a layer of complexity with many compounding effects. The supply chain is a complex non-linear system with many constraints increasing the need for strategic thinking, better modeling, and organizational alignment.

Let’s start with the COVID impact. This month marks the beginning of the third year of global supply chain leaders battling the effects of the COVID pandemic. The Normalcy Index calculated weekly by the Economist projects that North America is 67% of the way back to normalcy from COVID, but globally, it is lower at 50% with many flare-ups.

We have new variants and deaths in Hong Kong are at a record level as COVID outbreaks slow freight at Shenzhen and Qingdao ports in China. The Port of Shenzhen –a central manufacturing and export hub including the Yantian terminal that handles 25% of all U.S.-bound Chinese exports– is open. Still, the manufacturing plants and distribution centers are closed. Very little freight is moving with prices skyrocketing and many rerouting containers to Ningbo. The impact is multi-faceted.

The pandemic redefined work. Companies are still wrestling with the impacts of cancel-culture and the labor shortages from the great resignation. Supply chain teams are younger wanting easier-to-use solutions, and virtual teams need better and easier technologies to improve decision-making in a more variable world.

While not headline news, inflation is at a level not seen for fifty years. Crude and oil derivatives—and the impact as a feedstock to over 6000 different products—top the list. Oil reached a 14-year high of $130.50 a barrel on March 6th and continues to be volatile. The production cycles of oil and gas derivatives are struggling to adapt, creating imbalances. Major petrochemicals—including ethylene, propylene, acetylene, benzene, and toluene, and natural gas constituents like methane, propane, and ethane—are the feedstock chemicals for the production of many of the items we use and depend on every day. Shortages and price hikes will abound. The pending effect of fuel on logistics costs is an overlay for all companies struggling to manage the bottom line. Only 29% of companies can see and manage total costs and prepare for the influx of fuel surcharges.

Transportation constraints are also increasing with the risk of many drivers moving from logistics jobs delivering products to construction as the impact of the Infrastructure Deal becomes a reality. Yet, transportation optimization products focus on managing price, not the visibility of constraints. The reliability of first-pass tender is an ongoing issue. (Carriers agree to carry freight based on price contracts, but when the load is tendered they deny the load due to constraints. When this happens, companies turn to broker and LTL markets that are more volatile. There is a need for an overhaul.

Then there are the overarching issues of climate change. One of the most significant impacts is in the semiconductor industry. Taiwan manufacturers 60% of global semiconductors. Semiconductor manufacturing consumes 10% of the island’s water supply. Currently, there are ongoing issues from both a drought and energy resilience. Production is uncertain with few contingencies.

In the United States, fire activity increased in February and March 2022—fire is not just a California issue. Year-to-date, the number of United States fires and acres burned is nearly double the 10-year average, with more than 90% of the acres burned coming from the Southern states. Most of the West, Plains, and Texas remain in drought, with abnormally dry conditions across Florida and in portions of the Carolinas. Net/net? Climate change issues will grow to compound the issues.

Let’s Start With Demand

Yesterday, one of my clients asked, “Why were there so many issues during the pandemic?” I laughed. Sometimes the simplest questions are the best and the toughest.

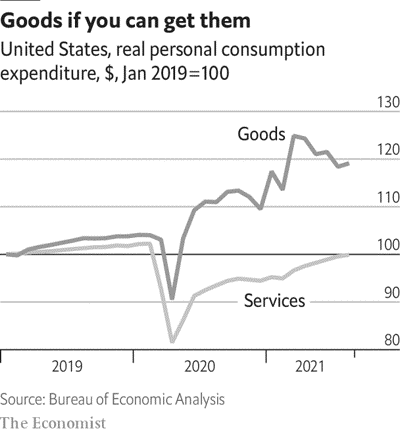

For me, Figure 1, tells the story. In the pandemic, the demand for goods skyrocketed, outstripping supply. With the surge, supply chains—accustomed to using the patterns of customer order and shipment data to predict future demand—were caught on the back foot. The greater the demand latency—the bigger the foot. For example, direct store delivery supply chains with 1-3 replenishment cycles adjusted quickly, while Over Counter Drugs (OTC) with replenishment cycles of 180-250 days are still adjusting. Yet, few supply chain leaders are willing to raise their hands and admit that current demand planning processes of forecasting based on order or shipments do not work.

Figure 1. Gross Volume Patterns of Goods and Services

In short, the pandemic was not a “risk management event.” Let me explain. While in the past, companies would react to a risk event by coming together globally ‘in a virtual war room’ to manage operations until a new normal is established–companies struggled in the pandemic because they were on the backfoot with disruption after disruption. There was no new normal. Instead, the new normal is disruption. Risk management practices assume the establishment of a new normal. This level of variability is unprecedented. Supply outstripped material and logistics capacities in the pandemic, yet we did not alter traditional practices to sense and drive a better response.

Now we layer on the impact of war. For humanity, the story is about personal tragedy and the loss of culture. Disheartening and sad…

For Europe, it is the impact of surging refugees and the rapid rise of energy costs. For manufacturers, it is about oil, gas, copper, helium, titanium, nickel, neon, and palladium from Russia and wheat, pig iron, and inert gases from Ukraine. A prolonged conflict between Russia and Ukraine could negatively impact Ukraine’s long-term ability to supply the raw material gases neon, argon, krypton, and xenon needed for semiconductor production. (Ukraine currently provides nearly 70 percent of the world’s neon gas capacity.) Food instability in Africa could be an outcome because Russia and Ukraine supply 29% of worldwide wheat exports and 17% of corn with significant exports to the middle east and Africa.

While the press report first-order impacts, supply chain leaders need to plan for the second and third-order impacts. These are not always obvious. For example, catalytic converters use palladium. Russia produces 40% of the world’s palladium. The rise in palladium prices will increase car theft of catalytic converters and drive a surge in demand in the market for guards to protect cars from theft. This is a third-order effect. Third-order effects will ripple uncontrollably through all supply chains.

Another example is medical/surgical supplies. The rise in COVID in China and war injuries will strip the world of medical/surgical supplies. Countries need to restock for new COVID variants and there should be a way to ensure that states and countries are not competing against each other with increasing prices.

In addition, the millions of refugees shifts demand not only in volume but also in preferences. As a result, the need for sensing increases, becoming more important to mitigate waste. Today’s supply chains cannot sense. The response is based on history which is not equal to the challenge.

Also expect disruption in transportation cycles. Ocean dwell times in Europe increased 55%, and goods initially bound for Russia are side-lined and queuing now– and potentially clogging later–global ports. Rail freight through Russia increased 40% last year. As the price for ocean freight increased in 2021, more and more goods moved from China to Europe by rail through Russia. On paper, it makes sense. A journey from China to Europe that takes 40 days by ship takes 15 days by rail. However, with the war, this is no longer an option. As a result, expect more and more goods to go by ocean to Europe. The congestion in China due to COVID and the repositioning from rail to ocean freight will elongate the cycles putting more pressure on ocean shipping and driving the need to rethink sourcing. More and more vessels will be committed to the China/Europe lanes causing an increase in costs for Asia North America.

Have I convinced you yet to get serious about variability?

A Need to Rethink Work

As time passes, second and third-level impacts become more evident. In the face of variability, I hope that supply chain leaders step back and rethink work to improve agility to help with this new level of variability. The journey needs to start with clear definitions. While responsiveness decreases the cycles to respond, agility is the design of the supply chain to have the same cost, quality, and customer service given the levels of demand and supply uncertainty. (Lots of leaders throw these words around without clear definitions.)

Current supply chain architectures assume that governments would be rational, variability would be low, and logistics would always be available. Quickly, you can assess that these three assumptions are no longer valid. While companies know that the bullwhip impact increases in the face of variability, the low levels of variability over the past three decades lulled leaders to sleep. It is time to face that the architecture advocated in 2000 is not equal to this challenge. The answer lies in market data with a lower dependency on enterprise data. The current architectures cannot effectively use market data and assume it is sufficient to use enterprise data.

Some additional considerations:

- Today, There Is No End-to-End Planning System. Just as there is no Santa Claus, companies cannot buy a planning technology that stretches from the customer’s customer to the supplier’s supplier. Instead, today’s planning solutions contain many optimization engines aligned to take transactional data and improve operational decisions within a function. There is no end-to-end planning to align make, source and deliver more effective in the tactical and operational horizons based on market signals. Let me give you an example, price management has nothing in common with demand planning, and Distribution Requirements Planning (DRP) has no commonality with transportation planning. These engines spin in isolation deep within functional silos using transactional inputs. This is not sufficient in the face of heightened variability.

- By Definition, Planning Solutions Are Not Adaptive. In most companies, planning solutions were implemented as a technology project versus a new way of doing business. As a result, few companies are aligned on what makes a good plan, and even fewer test to see if the solution output drives better outcomes. As a result, updates on planning parameters (planning master data) or tune-ups of engines (optimization) to test better results were no existent. Most were installed assuming dependency on transactional data within a static network parameters. As variability increases, there is a growing need for market data that cannot easily fit into existing architectures.

- S&OP Is Not A Panacea. In the past decade, there was a renaissance in Sales and Operations Planning (S&OP) termed Integrated Business Planning (IBP). The problem is that a single process cannot align data and organizational functions that are not naturally aligned. The implementation of the IBP model increased process latency (the time to make a decision) and in most organizations degraded Forecast Value Added (FVA) impacts on the demand plan.

- Traditional Risk Management Techniques Are Passe. When variability is the primary risk, the traditional definitions are thrown out of the window. There is no new normal. Instead, the solutions need to focus on “what-if modeling” and scenario simulation based on variability factors. Discrete event simulation is an underused technique that I am excited to see included in some of the newer digital twin solutions.

While many advocate the need to plan more frequently using conventional approaches, I argue this is not enough. This only makes organizations more reactive. I believe that companies need to build and test new architectures that are designed to use market data—to do this requires admitting that systems using relational database systems are legacy—and take six steps:

- Actively Design Flows Market-to-Market. Only 9% of companies actively design their supply networks using technologies that can model the market variability levels today. As a result, most companies lack a feasible plan. Unfortuntately, over 93% of companies use Excel Spreadsheets to develop their plans. We will never be successful modeling variability in an Excel spreadsheet.

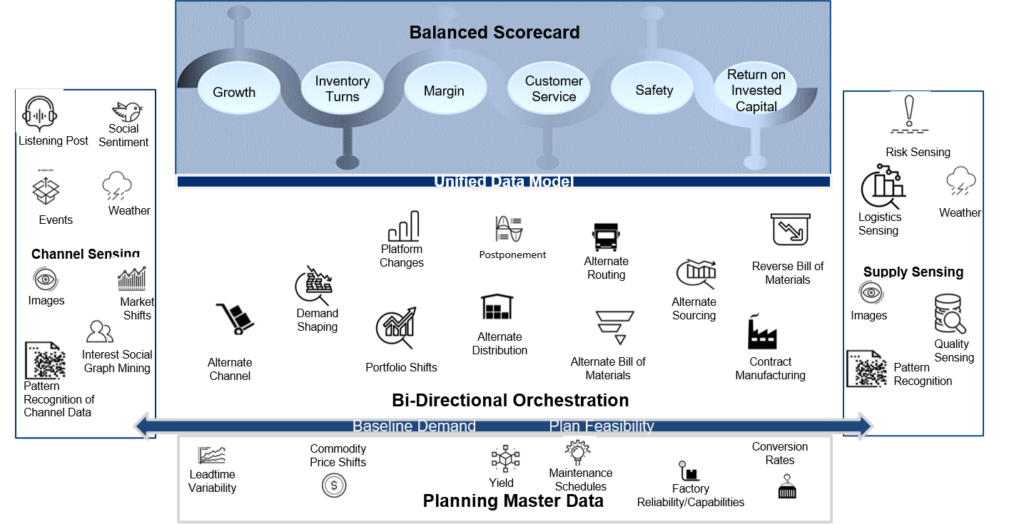

- Build a Unified Data Model. Not only do the taxonomies within planning not align (Example DRP to TMS), but organizations have multiple planning systems –sometimes different in regions and divisions—across teams. A unified data model allows the transference of a plan across different models, groups, and systems. The concept is that a unified data model—either graph, ontological representation, or a NoSQL approach allows for a cloud-based representation of trade-offs for modeling.

- Agree on Orchestration Levers. To manage variability across the organization requires clarity on what makes a good plan and the alignment on constraints. Then to balance and align, companies need to control the orchestration levers while recognizing the trade-offs of the Unified Data Model. The concept is alignment within the operational and executional period to drive success in S&OP execution, market replenishment/allocation strategies, and to improve customer centricity.

- Test and Learn on Market Data. The relative importance of market data changes over time. As a result, companies need to build models for both the channel and supply that can ingest multiple signals and rationalize the model based on the market parameters. The concept of multiple ifs to multiple thens is new for most teams and requires extensive testing to establish and implement. In my testing, I find that most companies need to include 20-30 signals for demand sensing. The relative importance changes over time.

- Build a Planning Master Data Layer. Market data needs to drive the models. As a result, there is a need for a planning master data layer to constantly update model parameters like cost, lead times, and conversion rates. Note the planning master data layer in Figure 2.

- Align to a Balanced Scorecard. Companies need to be aligned to a common set of metrics in a balanced scorecard to mitigate risk. Functional metrics introduce risk and throw the supply chain out of balance.

In Figure 2, I show a representation of a model for bi-directional orchestration.

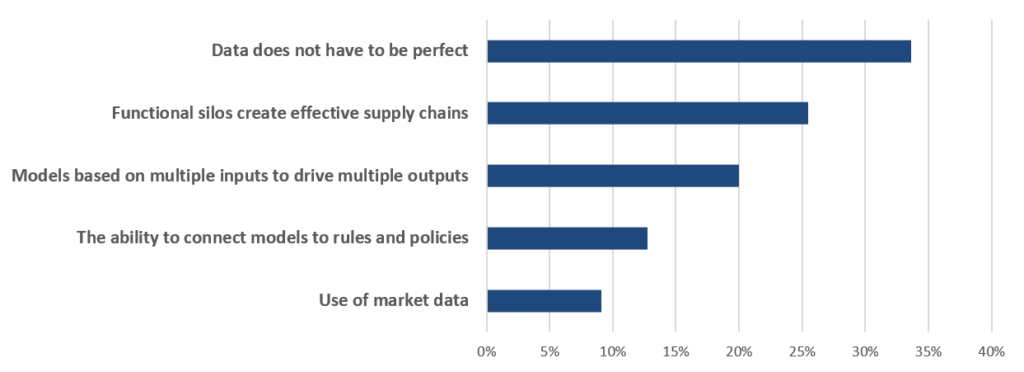

Embracing this type of model requires rethinking some of the basics of optimization. One of the most significant issues for students in my workshops is using data that is not perfect. Organizations are so accustomed to attempting to make data perfect that they introduce process latency. (Ironically, companies do not see the risk of stuffing a complex non-linear model like a supply chain into a relational data model as a risk. Or making a decision based on an Excel spreadsheet. This is when I scratch my head.)

Building outside-in processes requires rethinking our relationship with data. Machine learning techniques help us to mine imperfect data, and new forms of analytics enable the modeling of multiple inputs (again my tests show the need for 20-30 inputs of varying importance for demand) and the building of role-based outputs (think demand visibility across the organization). This thinking is new and requires challenging the basic paradigms of modeling.

Figure 3. Workshop Participant Feedback

Wrap-up

I am tired. For years, as an analyst, I spoke on building outside-in processes, but to no avail. Business leaders told me the approach was too academic, and the pilots I started were often killed by IT standardization initiatives. As I watch the world become more variabiale, I see the need, but there is no readily available solution in the market. Today’s software market is fueled by traditional sales techniques, pay-for-play conferences, and system integrators. A formidable force to challenge, but it is needed.

As variability increases in the supply chain, the concepts grow in importance. Unfortunately, most technologists are applying better math on top of existing taxonomies without rethinking how to redefine decision support to sense and drive a better response outside-in.

Last year, in frustration, I appealed to technology providers to redefine architectures. All but o9 Solutions were dismissive. Together, we launched Project Zebra as an open-source initiative to allow business leaders a safe space to test new concepts in the building of outside-in processes. Last week, we launched a Reverse RFP to allow manufacturers the opportunity to participate. Two companies will be selected to test the concepts of market-driven demand visibility and bi-directional orchestration.

The outcome of this work will be an input into the building of the new SCOR processes through work with ASCM. We will share the insights from the pilot testing here on my blog, and in case studies on Forbes and at the Supply Chain Insights Global Summit. Please follow. This is not about buying software, but rethinking what is possible. Companies need a safe place to test new concepts.